Combating Racism – Understanding Racial Violence – Part 2

EDITORIAL NOTE: In last week’s newsletter, the sub-heading 1868 – OPELOUSAS, GEORGIA should have been OPELOUSAS, LOUISIANA.

As I mentioned in last week’s newsletter, an opinion piece in The Washington Post by Walter Greason entitled, “We must honor those lost to violent racism,” inspired me to learn more about the history of racial violence in our country, especially those incidents before my adulthood. In last week’s newsletter, I covered the period between Antebellum and Post-Reconstruction America. But the first half of the 20th century was marked by continued race riots throughout the U.S. Hence, this and a subsequent newsletter about the topic. Warning: this is an R rated newsletter.

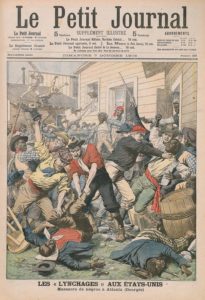

1906 – ATLANTA, GEORGIA

Atlanta race riot, Le Petit Journal, Oct 7, 1906

The Atlanta Riot of 1906 was the first race riot in the capital city of Georgia. The riot lasted from September 22 to September 24 and was the culmination of a number of factors, including lingering tensions from reconstruction, job competition, Black voting rights, and the increasing desire of Blacks to secure their civil rights.

By 1900 Atlanta’s population had more than doubled to 89,872 from its 1880 level. The Black population nearly quadrupled during that period. Job competition became intense and White politicians responded by implementing and expanding Jim Crow laws. The laws maintained separate Black and White neighborhoods, segregated public transportation, and segregated schools. Despite these hurdles, a small number of Black families achieved a significant measure of success. Black men voted during Reconstruction and continued to do so after their counterparts were pushed off the rolls throughout the rest of the South. Consequently there was considerable Black political activism in the city. The growing Black middle class made many White citizens uncomfortable but they were also wary of rising crime rates and the perceived threat of Black men against White women.

The 1906 gubernatorial campaign added fuel to the racial fire, as both Democratic candidates, Hoke Smith and Clark Howell, advocated disenfranchisement of all Black voters in their respective newspapers. On September 22, after four alleged sexual attacks on White women by Black men were reported in the local White press, a mob of approximately 10,000 White men surged through Black Atlanta neighborhoods destroying businesses and assaulting hundreds of Black men. The violence became so dangerous that the state militia was called in to take control of the city. Still, some White groups persisted in attacking Black neighborhoods, and Black men organized to defend their homes and families.

Prior to the 1906 riot, Atlanta was viewed as one of the few Southern American cities where Blacks and Whites could live in harmony. But in the aftermath of the violence the city became increasingly socially and racially stratified. The estimated number of Blacks killed was between 25 and 40 while two Whites were killed. Hundreds more people were injured or saw businesses and homes destroyed. Black residential neighborhoods became increasingly racially isolated following the riot, and many Blacks turned away from the previously popular accommodationist philosophies of Booker T. Washington in favor of more aggressive approaches to civil rights.

1908 – SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS

In mid-August 1908, the White population of Springfield, Illinois hastily reacted to reports that a White woman had been assaulted in her home by a Black man. Soon afterwards another instance of an assault by a Black man on a White woman was reported. These incidents, coming within hours of each other, inflamed a gathering mob.

Springfield Police took into custody a Black vagrant, Joe James, for one of the assaults. Another man, George Richardson, a local factory worker, was arrested for the second assault. A mob, which had been forming since the news of the assaults was first announced, now quickly assembled at the Sangamon County Courthouse to lynch the two men in custody.

Unable to get to the accused men whom the Sheriff had moved to an undisclosed location, the mob turned its wrath on two other Black men, Scott Burton and William Donegan. Donegan was an 84-year-old cobbler, whose reputation had been tainted in the eyes of the mob by the fact that he had been married to a White woman for over 30 years. They were quickly lynched.

The mob then vented its fury on the homes of Black families in Springfield. After rampaging through the city they extended their violence into small communities outside the city limits. The mob targeted stores which had guns and ammunition. Mob leaders carefully directed the participants to destroy only homes and businesses either owned by Blacks or which served Black patrons, thus leaving nearby White homes and businesses untouched.

When the carnage finally ended six Black people were shot and killed, two were lynched and hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of property destroyed. About two thousand Black people were driven out of the city of Springfield as a result of the riot.

About 150 suspected mob participants were arrested. Threats from mob participants restrained people from testifying against those suspected of the violence. Later it was revealed that George Richardson, who was initially charged with assault, had been wrongly identified and the indictment was dismissed.

The Springfield Riot made the capital of Illinois and the home of Abraham Lincoln the center of national attention especially since this was the first race riot in the North in over half a century. Perhaps the most lasting consequence of the riot was its impetus in getting White reformers such as Jane Addams and Black civil rights activists such as W.E.B. DuBois to create the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), one year later.

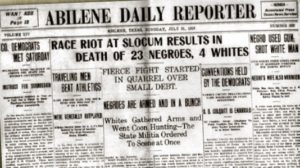

1910 – SLOCUM, TEXAS

The Slocum Massacre occurred on July 29, 1910 in Slocum, Texas, an unincorporated community in southeast Anderson County. The city used to be home to a thriving Black community with several businesses and farms owned by Black residents.

Leading up to the massacre, the lynching of a Black man in nearby Cherokee County sparked racial tensions in the Slocum area. White rumors circulated that Black residents had been meeting in Slocum to plan an armed rebellion. Racial tensions only intensified when a road construction foreman put a Black in charge of soliciting aid for road improvements. A confrontation erupted, enraging Jim Spurger, a local White farmer, who became the primary agitator of the conflict that led to the massacre. Many newspapers and eyewitness accounts reported that Spurger instigated the events by claiming that Blacks had threatened him.

Driven by Spurger and other White vigilantes, an angry mob of heavily armed White men from all over Anderson County roamed throughout Slocum in groups. Two hundred men laid siege to the city. They fired guns on Black residents at will. Blacks fled as word spread of the carnage. White mobs trailed fleeing Blacks into the surrounding forests and marshes and shot them in the back. Every initial newspaper portrayed Blacks as “armed instigators,” which were gross mischaracterizations.

Anderson County Sheriff William H. Black stated, at the time, that it was challenging to obtain the death toll because Black bodies had been scattered all over the woods. Many Black residents fled the town during and after the massacre, leaving behind real estate property and other assets to save their lives. White residents later seized their property. For instance, Jack Hollie, a formerly enslaved man, lost his dairy, granary, general store, and 700 acres of land to White residents after he and his family fled the city.

Spurger and at least fifteen other White men were arrested for the attacks. In addition, Spurger and six of the men were indicted on 22 counts of murder. However, they were never tried. None of the attackers were ever prosecuted.

Today, the city of Slocum reflects the relic of its history. While most nearby towns have Black populations of more than 20 percent, Slocum is just below seven percent. In 2016, a historical marker was dedicated to commemorate the event.

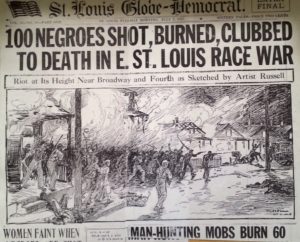

1917 – EAST ST. LOUIS, ILLINOIS

While three significant race riots occurred in 1917 – in Chester, Pennsylvania, Houston, Texas and East St. Louis, Illinois – East St. Louis was the site of one of the bloodiest race riots in the 20th century. Racial tensions increased in February, 1917 when 470 Black workers were hired to replace White workers who had gone on strike against the Aluminum Ore Company.

The violence started on May 28th, 1917, after angry White workers lodged formal complaints against Black migrations to the Mayor of East St. Louis. News of an attempted robbery of a White man by an armed Black man began to circulate through the city. As a result of this news, White mobs formed and rampaged through downtown, beating all Blacks who were found. The mobs also stopped trolleys and streetcars, pulling Black passengers out and beating them on the streets and sidewalks. Illinois Governor Frank O. Lowden eventually called in the National Guard to quell the violence, and the mobs slowly dispersed. The May 28th disturbances were only a prelude to the violence that erupted on July 2, 1917.

After the May 28th riots, little was done to prevent any further problems. No precautions were taken to ensure White job security or to grant union recognition. This further increased the already-high level of hostilities towards Blacks. No reforms were made in the police force which did little to quell the violence in May. Governor Lowden ordered the National Guard out of the city on June 10th, leaving residents of East St. Louis in an uneasy state of high racial tension.

On July 2, 1917, the violence resumed. Men, women, and children were beaten and shot to death. Around six o’ clock that evening, White mobs began to set fire to the homes of Black residents. Residents had to choose between burning alive in their homes, or run out of the burning houses, only to be met by gunfire. In other parts of the city, White mobs began to lynch Blacks against the backdrop of burning buildings. As darkness came and the National Guard returned, the violence began to wane, but did not come to a complete stop.

In response to the rioting, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) also responded to the violence. On July 8th, 1917, the UNIA’s President, Marcus Garvey said: “. . . that the police and soldiers did nothing to stem the murder thirst of the mob is a conspiracy on the part of the civil authorities to condone the acts of the White mob against Negroes.”

A year after the riot, a Special Committee formed by the United States House of Representatives launched an investigation into police actions during the East St. Louis Riot. Investigators found that the National Guard and also the East St. Louis police force had not acted adequately during the riots, revealing that the police often fled from the scenes of murder and arson. Some even fled from stationhouses and refused to answer calls for help. The investigation resulted in the indictment of several members of the East St. Louis police force.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

A series of twenty-five violent race riots, predominantly Whites against Blacks, which occurred between May and October 1919, became known as the “Red Summer,” in which an estimated 600 people died across the country. The migration of Blacks out of the south, the end of World War I, the illness and near incapacity of President Woodrow Wilson, and the 1918 influenza epidemic that killed more than 600,000 in the United States led to widespread social instability. These events lead to fears of social and political upheaval which contributed to racial tensions and violence as Whites sought scapegoats and Blacks, emboldened by their own progress, sought to defend their rights. Below is a small sampling of the riots of the “Red Summer.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

1919 – CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA

At the time the riot, Charleston was a city of 80,000, more than half of whom were Black. On the evening of May 10, 1919, a Black man allegedly pushed Roscoe Coleman, a White Navy sailor, off the sidewalk. A White crowd of sailors and civilians gave chase to the man, who had escaped to a nearby house. A scuffle ensued where both sides threw bricks, bottles, and stones, until four shots were fired into the air by a Black man to disperse the crowd. Rumors immediately began to circulate of a sailor “shot by a Negro.”

Rioting by White sailors, civilians, and a few soldiers and marines soon began, the multiplicity of the crowd makeup adding further chaos and hysteria to the scene. A mob of sailors stole rifles from nearby gun clubs and began shooting Blacks indiscriminately while robbing and vandalizing Black-owned businesses along the way. Blacks fought back using firearms of their own. The rioting continued until around 3:00 a.m. when Charleston’s mayor requested a detachment of U.S. Marines to restore order. In all, five White men and 18 Black men were seriously injured, and three Black men died of gunshot wounds.

The subsequent Navy investigation stands as one of the very few official documents regarding White racial violence during the era where the White perpetrators were named and their crimes identified. The report found sailors Ralph Stone, George W. Biggs, Roscoe Coleman, Robert Morton, and White civilian resident Alexander Lanneau were responsible for “stirring up strife and inciting others to violence against the negroes.” In addition, it found Jacob Cohen and George T. Holliday, both sailors, jointly responsible for the death of Isaac Doctor. Finally, it declared that “all property damage,” save a poolroom, and “all injuries to negro men…was caused by the unlawful actions of mobs, which in all cases were comprised principally of sailors.”

However, typical of White mob violence in the United States at the time, very little punishment was meted out. Despite the thorough and objective investigation and its naming of culprits, and despite the Navy’s full authority to hand out harsh sentences then standard for misconduct, Cohen and Holliday received only one year in military prison as punishment and no other sailors, soldiers, marines or civilians were convicted of any unlawful acts.

1919 – CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

Crowd and armed National Guard soldiers, outside Ogden Cafe, Chicago, 1919

(Public Domain Image)

On July 27, 1919 when large crowds of White and Black patrons went to the Lake Michigan beach in Chicago, Illinois to seek relief from the 96 degree heat, an angry dispute erupted over the stoning of Eugene Williams, a young Black swimmer who inadvertently crossed a segregated boundary into the “White” swimming area. White beachgoers hailed stones at the young man causing him to drown. When police refused to arrest any Whites, who were accused by Black bystanders of having thrown the stones and instead arrested a Black beachgoer on a White’s complaint of some minor offense, the Blacks began to attack the White policemen. Reports of the incident spread throughout Chicago igniting a clash of White and Black rioters across the city’s South Side.

This incident released years of accumulated racial tensions, starting from a constricting job market and the efforts by Chicago Blacks to secure adequate housing by moving into previously all-White neighborhoods as thousands of Blacks began arriving in the city during World War I as part of what would be called the Great Migration.

For seven days, bloodshed was rampant on the streets of Chicago. Many Blacks became victims of White mobs when they had to pass through White neighborhoods in order to reach their workplaces. Others were attacked on streetcars or in city parks and other public venues. The majority of the rioting and violence was concentrated in the “Black Belt” section, the predominantly Black neighborhoods on the South Side of Chicago.

At the height of the rioting, over four-fifths of Chicago’s 3,500 police officers had been sent to control the angry crowds. Many Blacks stayed home fearing mob violence. They often were not safe there as White mobs began to torch houses in Black neighborhoods. Blacks fought back. Often gangs of men attacked and stabbed White civilians, but White rioters had superiority in numbers and firepower and in many cases the sympathy of the police.

By the end of the violence twenty-three Blacks and fifteen Whites died, with more than five-hundred people injured and about a thousand people left homeless.

1919 – ELAINE, ARKANSAS

One of the major riots of the “Red Summer” of 1919, the race riot in Elaine, Arkansas was in fact a racial massacre. Though exact numbers are unknown, it is estimated that over 200 Blacks were killed, along with five Whites, during the White hysteria of a pending insurrection of Black sharecroppers.

On the night of September 30, 1919, approximately 100 Blacks, mostly sharecroppers on the plantations of White landowners, attended a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America at a church in Hoop Spur, a small community in Phillips County, Arkansas. They hoped to organize to obtain better payments for their cotton crops. Aware of White fears of Communist influence on Blacks, the union posted armed guards around the church to prevent disruption and infiltration.

During the meeting, three White men pulled up to the front of the church. One of the men asked the guards, “Going coon hunting, boys?” Gunfire erupted after the guards made no response. Though sharp debate exists as to who fired first, the guards killed a security officer from the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, and injured the deputy sheriff.

The next morning, an all-White posse went to arrest the suspects. Though they encountered little opposition from the Black community, the fact that Blacks outnumbered Whites ten-to-one in this area of Arkansas resulted in great fear of an “insurrection.” The concerned Whites formed a mob numbering up to 1,000 armed men, many of whom came from the surrounding counties and as far away as Mississippi and Tennessee. Upon reaching Elaine, the mob began killing Blacks and ransacking their homes. As word of the attack spread throughout the Black community, some Black residents fled while others armed themselves in defense. The mob then turned its attention to disarming those Blacks who fought back.

Meanwhile, local White newspapers further inflamed tensions by reporting that there were planned Black uprisings. By October 2, U.S. Army troops arrived in Elaine, and the White mobs began to disperse. Federal troops rounded up and placed several hundred Blacks in temporary stockades, where there were reports of torture. The men were not released until their White employers vouched for them. There was also considerable evidence that many of the soldiers sent to quell the violence engaged in the systematic killing of Black residents.

In the end, 122 Blacks but no Whites were charged by the Phillips County grand jury for crimes related to the riots. The first 12 men tried for first-degree murder were convicted and sentenced to death. As a result, 65 others entered plea bargains and accepted up to 21 years for second-degree murder. Led by Black attorney Scipio Africanus Jones, the NAACP and other civil rights groups worked towards retrials and release of the “Elaine Twelve.” Eventually they won their release, with the last of the twelve set free on January 14, 1925.

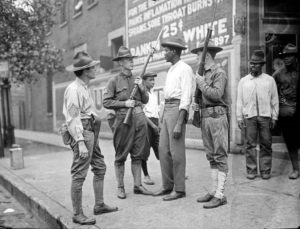

1919 – WASHINGTON, D.C.

Armed National Guards and African American men on sidewalk, 1919

(Public domain image)

Lasting a total of only four days, this short-lived riot was more accurately described as a “race war” taking place in the nation’s capital.

On Saturday night, July 19, 1919, in a downtown bar, a group of White veterans sparked a rumor regarding the arrest, questioning, and release of a Black man suspected by the Metropolitan Police Department of sexually assaulting a White woman. The victim was also the wife of a Navy man. The rumor traveled throughout the saloons and pool halls of downtown Washington, angering the several soldiers, sailors, and marines taking their weekend liberty, including many veterans of World War I.

Later that Saturday night, a mob of veterans headed toward Southwest D.C. to a predominantly Black, poverty-stricken neighborhood with clubs, lead pipes, and pieces of lumber in hand. The veterans brutally beat all Blacks they encountered. Blacks were seized from their cars and from sidewalks and beaten without reason or mercy by White veterans, still in uniform, drawing little to no police attention.

On Sunday, July 20, the violence continued to grow, in part because the seven-hundred-member Metropolitan Police Department failed to intervene. Blacks continued to face brutal beatings in the streets of Washington, at the Center Market on Seventh Street NW, and even in front of the White House.

By the late hours of Sunday night, July 20, the Black community began to fight back. They armed themselves and attacked Whites who entered their neighborhoods. Both Black and White men fired bullets at each other from moving vehicles. At the end of the night, ten Whites and five Blacks were either killed or severely wounded.

After four days of violence and no police intervention, President Woodrow Wilson finally ordered nearly two thousand soldiers from nearby military bases into Washington to suppress the rioting. However, a heavy summer rain, rather than the troops themselves, effectively ended the riot on July 23, 1919.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Above are just a few examples of the racial violence that occurred during the “Red Summer” of 1919. The killing and destruction, and racial violence against Blacks continued through the first half of the 19th century with equal malice.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

1920 – OCOEE, FLORIDA

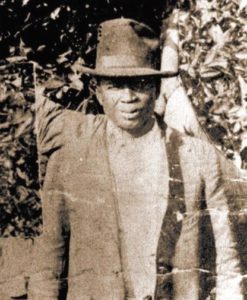

Julius July Perry

The Ocoee massacre was a White mob attack on Black residents in northern Ocoee, Florida approximately 12 miles northwest of Orlando. Occurring on November 2, 1920, the day of the U.S. presidential election, this massacre was the largest election-related massacre in the 20th century. Ocoee, in Orange County, had been politically dominated by conservative Democrats since the end of Reconstruction. They prided themselves in keeping Blacks, then mostly Republicans, from the polls.

For a year before the 1920 election, a number of Black organizations across Florida began conducting voter registration campaigns. Black people had essentially been disfranchised in Florida since the beginning of the 20th century. Mose Norman, a prosperous Black farmer who worked on the voter drive, tried to vote but was turned away twice on Election Day.

When Norman was driven away a second time, a White mob of over 100 men decided to hunt him down. The mob surrounded the home of Julius “July” Perry, where Norman was thought to have taken refuge. After Perry drove away the White mob with gunshots, killing two men and wounding one who tried to break into his house, the mob called for reinforcements. They killed Perry and hanged his body from a light post in Orlando to intimidate other Black people. Norman escaped, never to be found.

The mob then turned on the Black community of Ocoee. Most Black-owned buildings and residences in northern Ocoee were burned to the ground. Other Blacks living in southern Ocoee were later killed or driven out on threat of more violence. The entire Black population fled the town, leaving behind their homes and possessions. Some Blacks speculated that the rioting may have been planned so that Whites could seize the property of the wealthiest Blacks in the town.

Most estimates total 30 Black people killed. Ocoee essentially became an all-White town. The massacre has been described as the “single bloodiest day in modern American political history”.

According to Pamela Schwartz, chief curator of the Orange County Regional History Center, for almost a century, many descendants of survivors were not aware of the massacre that occurred in their hometown. On June 21, 2019, a historical marker honoring July Perry and others killed in the massacre was placed in Heritage Square outside the Orange County Regional History Center.

1921 – TULSA, OKLAHOMA

The Tulsa, Oklahoma race massacre was one of the worst urban racial conflicts in United States history. Two days of violence by Whites against Blacks left an estimated 100-300 people dead, hundreds injured, and more than 1,000 Black-owned homes and businesses destroyed.

The riot, which began on May 31, 1921, was initiated by an incident that happened the day before. On the morning of May 30, a Black man named Dick Rowland stepped into Tulsa’s Drexel Building to use the restroom. The elevator operator was a young White woman named Sarah Page. A scream was heard from inside the elevator, and Rowland ran out. While there was no conclusive evidence, Whites in Tulsa believed that Rowland attempted to assault Page.

Rowland was arrested, and subsequent headlines in local newspapers stirred up the White and Black populations of Tulsa. Talk of lynching arose among Whites, and a crowd of Whites and Blacks gathered outside the courthouse where Rowland was being held on the night of May 31. A gun discharged while a White man was trying to disarm a Black man, causing the incident to erupt into a much larger racial conflict.

At the eruption of violence, civil officials selected many men, all of them white and some of them participants in that violence, and made those men their agents as deputies. In that capacity, deputies did not stem the violence but added to it, often through overt acts that were themselves illegal. Public officials provided fire arms and ammunition to individuals, again all of them white.

By the early morning of June 1, the wholesale burning and pillaging of Black Tulsa had begun. Entering the Greenwood district, people, some of them agents of government, deliberately burned or otherwise destroyed homes credibly estimated to have numbered 1,256, along with virtually every other structure — including churches, schools, businesses, even a hospital and library — in the Greenwood district. Despite duties to preserve order and to protect property, no government at any level offered adequate resistance, if any at all, to what amounted to the destruction of the Greenwood neighborhood.

Despite being numerically at a disadvantage, black Tulsans fought valiantly to protect their homes, their businesses, and their community. But in the end, the city’s African-American population was simply outnumbered by the white invaders.

The National Guard declared martial law throughout the city at 11:29 am, bringing an end to most violence. The Guard then began rounding up Blacks for internment. Most White rioters returned to their homes the night of June 1, while much of Tulsa’s Black population was imprisoned.

In the wake of the violence, 35 city blocks lay in charred ruins, more than 800 people were treated for injuries and historians now believe that as many as 300 people may have died. Not one of these criminal acts was then or ever has been prosecuted or punished by government at any level.

It took nearly a decade for Tulsa to recover from the physical destruction it endured from the riot. Despite its significance, both Black and White Tulsans claim the incident has been “hushed up” and not adequately recognized. It was scarcely mentioned in history books, especially Oklahoman history books.

In 1996, Oklahoma formed a commission to investigate the riot and prepare a historical account. The Tulsa Race Massacre Commission issued its report in February 2001. It recommended restitution for Black survivors and their descendants; a scholarship fund for descendants; economic development in the Greenwood district; and a memorial for the victims.

1923 – ROSEWOOD, FLORIDA

The ruins of the two-story shanty near Rosewood, Florida, in 1923 where Black residents barricaded themselves and fought off a band of Whites. Photograph: Bettmann/CORBIS

Burning of Black resident’s home, Rosewood, 1923

(Public domain image detail)

Rosewood, in central Florida, was originally settled in 1845 by both Blacks and Whites until Black codes and Jim Crow laws after the Civil War fostered segregation in Rosewood (and much of the South). Employment was provided by pencil factories, but the cedar tree population soon became decimated and White families moved away in the 1890s and settled in the nearby town of Sumner. By the 1920s, Rosewood’s population of about 200 was entirely made up of Black citizens, except for one White family that ran the general store there.

On January 1, 1923, a massacre was carried out in the small town of Rosewood. The massacre was instigated by the rumor that a White woman, Fanny Taylor, had been assaulted by a Black man in her home in a nearby community. A group of White men, believing this assailant to be a recently escaped convict named Jesse Hunter who was hiding in Rosewood, assembled to capture Hunter.

Fannie Taylor’s husband, a foreman at the local mill, escalated the situation by gathering an angry mob of White citizens to hunt down the culprit. He also called for help from White residents in neighboring counties, among them a group of about 500 Ku Klux Klan members who were in Gainesville for a rally. The White mobs prowled the area woods searching for any Black man they might find.

The White men began to search for Jesse Hunter along with Aaron Carrier and Sam Carter, who were believed to be accomplices. Carrier was captured and incarcerated while Carter was lynched.

As many as 25 people, mostly children, had taken refuge in the home of Sarah Carrier when, on the night of January 4,1923, a group of 20 to 30 armed White men surrounded the house in the belief that Jesse Hunter was hiding there.

They approached the Carrier home and shot the family dog and Sylvester’s mother Sarah when she came to the porch to confront the mob. Aaron’s cousin, Sylvester, defended his home, killing two men and wounding four in the ensuing battle. The horde of White men dragged Carrier out of his house, tied him to a car and dragged him to Sumner, where he was cut loose and beaten. The gun battle and standoff lasted overnight. It ended when the door was broken down by White attackers. The children inside the house escaped through the back and made their way to safety through the woods, where they hid.

A White mob found Sarah’s son, who had taken refuge with the help of a local turpentine factory manager, and forced him to dig a grave for himself before murdering him.

Another mob showed up at the home of Blacksmith Sam Carter, torturing him until he admitted that he was hiding Hunter and agreed to take them to the hiding spot. Carter led them into the woods, but when Hunter failed to appear, Carter was shot, and his body was hung on a tree before the mob moved on.

News of the standoff at the Carrier house spread, with newspapers falsely reporting bands of armed Black citizens going on a rampage. Even more White men poured into the area believing that a race war had broken out.

Some of the first targets of this influx were the churches in Rosewood, which were burned down. Houses were then attacked, first setting fire to them and then shooting people as they escaped from the burning buildings.

Many Rosewood citizens fled to the nearby swamps for safety, spending days hiding there. Some attempted to leave the swamps but were turned back by men working for the sheriff. Florida Governor Cary Hardee offered to send the National Guard to help, but Sheriff Walker declined the help, believing he had the situation under control.

Mobs began to disperse after several days, but on January 7, many returned to finish off the town, burning what little remained of it to the ground, except for the home of John Wright. At the end of the carnage, only two buildings remained standing, a house and the town general store. As a consequence of the massacre, Rosewood became deserted.

The initial report of the Rosewood incident, presented less than a month after the massacre, claimed there was insufficient evidence for prosecution. Thus, no one was charged with any of the Rosewood murders. The surviving citizens of Rosewood did not return, fearful that the horrific bloodshed would recur.

In 1982, Gary Moore, a journalist for the St. Petersburg Times, resurrected the history of Rosewood through a series of articles that gained national attention. With Jim Crow laws lifted, and lynch mob justice no longer a mortal threat, the living survivors of the massacre, at that point all in their 80s and 90s, came forward, and demanded restitution from Florida.

In 1994, as the result of new evidence and renewed interest in the event, the Florida Legislature passed the Rosewood Bill which entitled the then-elderly nine survivors to $150,000 dollars each in compensation, and created a scholarship fund. The law, which provided $2.1m total for the survivors, improbably made Florida one of the only states to create a reparations program for the survivors of racialized violence.

The events of Rosewood were subsequently dramatized in John Singleton’s 1997 film, Rosewood.

1943 – BEAUMONT, TEXAS

The Beaumont Race Riot of 1943 was sparked by racial tensions that arose in this Texas shipbuilding center during World War II. The sudden influx of Black workers in industrial jobs in the Beaumont shipyard and the subsequent job competition with White workers forced race relations to a boiling point.

The riot itself exploded on June 15, 1943 with most of the violence ending a day later. White workers at the Pennsylvania Shipyard located in Beaumont, Texas confronted Black workers after hearing that a local White woman had accused a Black man of raping her. The woman who made the accusation was later unable to identify her attacker from the number of Black inmates held at the city jail.

Nonetheless, on the evening of June 15, about 2,000 shipyard workers and an additional 1,000 bystanders marched on City Hall when they learned that a suspect had been jailed. The number of people eventually reached 4,000 as the mob reached City Hall. Once there, the mob splintered into smaller groups and began to break into stores and destroy property located in the Black neighborhoods near downtown Beaumont. Black citizens were assaulted while Whites looted and burned Black stores and restaurants. More than 100 homes of Black Beaumont residents were ransacked.

Mayor George Gary called in the Texas National Guard late on the night of June 15, and acting governor A.M. Aiken Jr. declared Beaumont to be under martial law. About 1,800 guardsmen entered Beaumont along with 100 state police and 75 Texas Rangers at that time. Upon their arrival an 8:30 p.m. curfew was established.

The Texas Highway Patrol sealed the city off against rural Whites who threatened to join the mob. Within the town, all activity came to a halt. Black workers were barred from going to work. The curfew was lifted the next day on June 16, and the guardsmen left the town.

Martial law was lifted on June 20. During the five day period 21 people were killed. No one was specifically held responsible for the deaths during the riot. Although Black and White workers returned to the Pennsylvania Shipyard, war production in the area was slowed for months.

1943 – DETROIT, MICHIGAN

The Detroit Riot of 1943 lasted only about 24 hours from 10:30 on June 20 to 11:00 p.m. on June 21; nonetheless it was considered one of the worst riots during the World War II era. Several contributing factors revolved around police brutality, and the sudden influx of Black migrants from the south into the city, lured by the promise of jobs in defense plants. The migrants faced an acute housing shortage which many thought would be reduced by the construction of public housing. However the construction of public housing for Blacks in predominately White neighborhoods often created racial tension.

In 1942, for example, Whites were enraged by the opening of the Sojourner Truth Homes project in their neighborhood. Mobs attempted to keep the Black residents from moving into their new homes. That confrontation laid the foundation for the much larger riot one year later.

On June 20, a warm Saturday evening, a fist fight broke out between a Black man and a White man at the sprawling Belle Isle Amusement Park in the Detroit River. The brawl eventually grew into a confrontation between groups of Blacks and Whites, and then spilled into the city. Stores were looted, and buildings were burned in the riot, most of which were located in a Black neighborhood. The riot took place in an area of roughly two miles in and around Paradise Valley, one of the oldest and poorest neighborhoods in Detroit.

As the violence escalated, both Blacks and Whites engaged in violence. Blacks dragged Whites out of cars and looted White-owned stores in Paradise Valley while Whites overturned and burned Black-owned vehicles and attacked Blacks on streetcars along Woodward Avenue and other major streets. The Detroit police did little in the rioting, often siding with the White rioters in the violence.

The violence ended only after President Franklin Roosevelt, at the request of Detroit Mayor Edward Jeffries, Jr., ordered 6,000 federal troops into the city. Twenty-five Blacks and nine Whites were killed in the violence. Of the 25 Blacks who died, 17 were killed by the police. The police claimed that these shootings were justified since the victims were engaged in looting stores on Hastings Street. Of the nine Whites who died, none were killed by the police. The city suffered an estimated $2 million in property damages.

1946 – COLUMBIA, TENNESSEE

The race riot in Columbia, Tennessee, a town of 10,911, from February 25 to 28, 1946 was an early example of post-World War II racial violence between Blacks and Whites. It is significant for the self-defense role of Black veterans of World War II and the legal defense mounted by the NAACP attorneys such as Thurgood Marshall.

On February 25, 1946, James Stephenson, a World War II veteran, and his mother, Gladys Stephenson, went to a local department store to pick up their repaired radio, only to learn it had been sold to another customer. When Mrs. Stephenson demanded the radio, William Fleming Jr., a store employee, struck her. Defending his mother, Stephenson began fighting Fleming who crashed through a window. Stephenson and his mother were arrested and charged with disturbing the peace.

Both pleaded guilty and received a $50 fine. The situation escalated after William Fleming Sr. filed charges against them on behalf of his son for assault with the intent to commit murder. The Stephensons were arrested again. A local Black businessman posted the Stephensons’ bond and they were released.

During the same time, a White mob after hearing about the fight between Fleming and Stephenson, gathered at the Maury County Courthouse. In the Black business section, called Mink Slide, Black townspeople, some of them World War II veterans, came together. Concern about the possibility of mob violence against the entire Black community prompted many of them to arm themselves. Four white policemen entered Mink Slide after disregarding warnings from the Black community to stop. Shots were fired and the officers were wounded.

Following the shooting, Tennessee State Safety Commissioner Lynn Bomar led other police officers and state highway patrolmen into Mink Slide. In the early morning hours of February 26, patrolmen and white surrounded the Black district. They looted Mink Slide, illegally searched homes, fired indiscriminately into buildings, stole residents’ property and confiscated weapons. Dozens were arrested but denied bail and legal counsel. During the confrontation, more than one hundred Black women and men were arrested.

The executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Walter White, and chief legal counsel Thurgood Marshall, came to Columbia to organize a defense for the remaining prisoners.

In nearby Lawrenceburg, twenty-five Columbia Blacks were tried on charges of shooting at the White policemen. On October 4, 1946, an all-White jury surprisingly found only two of the twenty-five Blacks guilty, and the charges were later dropped. One reason for the verdict: many Whites in Lawrenceburg felt embarrassed that trial had to take place there instead of Columbia where the riot occurred. The Columbia Race Riot of 1946 foreshadowed the growing militancy of Blacks that would be seen in the numerous urban uprisings of the 1960s.

1949 – PEEKSKILL, NEW YORK

The Peekskill Riot was a series of violent attacks by mobs of White citizens directed against Blacks and Jews attending a civil rights benefit concert in Westchester County, New York, in 1949. More than 150 people were injured in the riots.

The concert, planned as a benefit for the Civil Rights Congress, a legal defense organization founded in 1946, was scheduled to take place on August 27 in Peekskill, New York. The concert’s headline act was Paul Robeson, the singer and actor whose communist sympathies and outspokenness on issues of racial equality led him to be blacklisted during the McCarthy era.

Just before Robeson arrived in Peekskill, a mob of 300 local residents including many youth, attacked concert attendees with sticks, clubs, and rocks. Rioters lynched an effigy of Robeson, burned a cross on the concert grounds, and chanted, “Go home Commies” and “Dirty Kikes” (the latter slur was likely a reference to Helen Rosen, a friend of Robeson’s and one of the concert organizers). Members of the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars participated in the attacks, while local police refused to respond. Thirteen people were injured. Concert organizers decided to postpone the event until September 4.

In the interim, local labor unions, including the Longshoremen and United Electrical Workers, agreed to provide security for the rescheduled concert. The September 4 concert proceeded without incident with 20,000 people in attendance. In addition to Robeson, performers included folk singers Pete Seeger and Hope Foye, and pianists Leonid Hambro and Ray Lev.

After the concert, however, as performers and attendees left the open-air venue by car, mobs gathered on the roadway and on the hillside above pelted the cars with rocks. Some individuals were pulled from their vehicles and beaten. Eugene Bullard, the World War One combat pilot, was beaten by state troopers and local police officers. No arrests, charges, or citations were enforced against any of the rioters. One hundred and forty people were injured in the second round of attacks.

In the weeks after the riots, New York state officials, members of Congress, and many national news organizations blamed Robeson and concert organizers for provoking the violence. Dozens of Robeson’s concert bookings were canceled by communities fearful that violent protests might reoccur. In September 1999, on the fiftieth anniversary of the riots, Westchester County held a “Remembrance and Reconciliation Ceremony” at which county officials made a formal apology to the victims of the attacks. Paul Robeson Jr. and Pete Seeger, then 80 years old, participated in the ceremony.

How do we know what we know?

By being educated and by lived experience. If you’re like me, you haven’t had either as it relates to these atrocities.

How do we know what we don’t know?

By asking questions, reading books and articles, watching films, taking courses, attending conferences, and having difficult conversations with others. In reading this history and other resources, we can learn what we don’t know and begin the growth necessary to unite and strengthen our communities and our country.

While numerous sources were used in this and last week’s newsletters, the primary source material came from Blackpast.org.