Combating Racism – Lest They be Forgotten – Part 1

Many talented members of the Black community have given much to our country and yet their achievements went unrecognized for a long time.

Textbooks and classrooms in the 1950s, ‘60s and ’70s mainly provided the history of Caucasian Americans. Despite being a crucial component in the American story, the lives of many important Black Americans were rarely mentioned in history classes.

Recognition of skilled and gifted Black scientists, engineers and inventors has suffered under racial prejudices and unjust negative stereotyping. Racist generalizations have been at the root of race-based discrimination for decades.

When we suspend our disbelief and see each person as an individual rather than through the eyes of a preconceived stereotype, we can begin to change this on an individual level. Then, change on the community and societal levels can occur.

It is this stereotyping that I hope to debunk by sharing the stories of successful Black scientists, engineers, and inventors – people whose works have contributed to our country’s progress and enriched our day-to-day lives in significant ways. I have researched many Black men and women (primarily those born in the 19th century) who surmounted racial prejudice to go on to make significant improvements to America. This week I am sharing those whose names begin with B through J. Next week I’ll continue with those whose names begin with L through W.

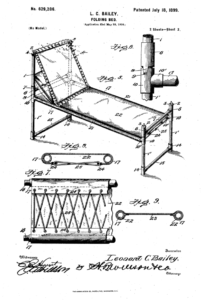

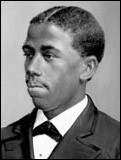

LEONARD C. BAILEY (1825-1918) – TRUSS AND BANDAGE; FOLDING BED

Leonard C. Bailey was born in 1825 to a free Black family. Growing up in poverty, Bailey worked as a barber and built up a string of barbershops in Washington D.C.

Bailey’s desire to help the Black community led to his founding the Capitol Savings Bank of Washington, D.C. in October 1888 – one of the first Black-owned banks in the U.S. Bailey and seven other Black businessmen created the bank to provide more affordable loans and insurance for poor households. Bailey served as the bank’s president for several years before becoming head treasurer and a director of its finance board. During the Panic of 1893, one of the country’s worst financial crises, the Capitol Savings Bank was one of the few banks in Washington, D.C. to maintain its solvency. Due to this resilience, Capitol Savings became a trusted bank for both Blacks and Whites in the DC area.

Aside from his accomplishments as a businessman and community member, Bailey is also significant for his inventions. In 1883, Bailey patented one of his most important devices, a truss-and-bandage intended to support patients with lower-body hernias to prevent enlargement of a hernia or the return of a reduced hernia.

The design was later adopted by the U.S. Army Medical Board, providing funding for Bailey’s business ventures and future inventions. Among these were a device for moving railway trains and a speed stamper for mail, the latter being used most frequently by the U.S. Postal Service.

On July 18, 1899, Bailey patented a folding bed for easy storage. Again, the US Army welcomed the innovation which is Bailey’s claim to fame in the present day.

ALICE AUGUSTA BALL (1892-1916) – CHEMIST – LEPROSY TREATMENT

After earning undergraduate degrees in pharmaceutical chemistry (1912) and pharmacy (1914) from the University of Washington, Alice Ball transferred to the College of Hawaii (now known as the University of Hawaii) and in 1915 became the very first Black and the very first woman to graduate with a M.S. degree in chemistry. She was offered a teaching and research position there and became the institution’s very first woman chemistry instructor. She was only 23 years old.

As a laboratory researcher, Ball worked extensively to develop a successful treatment for those suffering from Hansen’s disease (leprosy). Her research led her to create the first successful leprosy treatment using oil from the chaulmoogra tree. Ball successfully isolated the oil into fatty acid components of different molecular weights allowing her to manipulate the oil into a water soluble injectable form. Ball’s scientific rigor resulted in a highly successful method to alleviate leprosy symptoms, later known as the “Ball Method,” that was used on thousands of infected individuals for over thirty years until sulfone drugs were introduced.

The “Ball Method” was so successful, leprosy patients were discharged from hospitals and facilities across the globe. Thanks to Alice Ball, these banished individuals could now return to their families, free from the symptoms of leprosy.

Tragically, Ball died on December 31, 1916, at the age of 24 after complications resulting from inhaling chlorine gas in a lab teaching accident. During her brief lifetime, she did not get to see the full impact of her discovery. What’s more, following her death, the president of the College of Hawaii, Dr. Arthur Dean, continued Ball’s research without giving her credit for the discovery. Dean even claimed her discovery for himself, calling it the “Dean Method.” Unfortunately, it was commonplace for men to take the credit of women’s discoveries and Ball fell victim to this practice.

In 1922, six years after her death, Dr. Harry T. Hollmann, the assistant surgeon at Kalihi Hospital who originally encouraged Ball to explore chaulmoogra oil, published a paper giving Ball the proper credit she deserved. Even so, Ball remained largely forgotten from scientific history until recently. In 2007, the University of Hawaii posthumously awarded her with the Regents’ Medal of Distinction. In 2017, Paul Wermager, a scholar who has been researching, publishing and lecturing about Ball for years stated:

“Not only did she overcome the racial and gender barriers of her time to become one of the very few African American women to earn a master’s degree in chemistry, [but she] also developed the first useful treatment for Hansen’s disease. Her amazing life was cut too short at the age of 24. Who knows what other marvelous work she could have accomplished had she lived.”

MIRIAM BENJAMIN (1861-1947) – GONG AND SIGNAL CHAIR

Miriam Elizabeth Benjamin attended high school in Boston before moving to Washington, D.C. in the 1880s. During her time in Washington, Benjamin worked as a teacher and in the federal civil service as a government clerk.

On July 17, 1888, Miss Benjamin became the second African American woman to receive a patent from the United States government. The patent was for her invention of a gong and signal chair.

Benjamin aimed to transform several industries with her innovation, including hotels, theaters, healthcare, and government. The key feature of the chair was a notification system, which allowed the seated individual to press a small button on the back of the chair which then sent a signal to a waiting attendant. By depressing the button, a gong or ring would sound at the same moment that a light would illuminate, allowing the attendant to see which guest needed help. The chair would “reduce the expenses of hotels by decreasing the number of waiters and attendants, to add to the convenience and comfort of guests and to obviate the necessity of hand clapping or calling aloud to obtain the services of pages.”

Benjamin’s invention received attention in the press and was featured in newspapers across the country. The system was eventually adopted by the United States House of Representatives and was a precursor to the signaling system used on airplanes for passengers to seek assistance.

Benjamin likely also had success as a composer. Music historians believe she (under the pseudonym E.B. Miriam) composed at least two prominent marches. The United States Marine Band under John Philip Sousa performed one piece, “The Boston Elite Two Step,” in the early 1890s. Another composition, “The American Bugle Call,” gained even more attention as the campaign song for the 1904 Presidential Campaign of Theodore Roosevelt.

HENRY BLAIR (1807-1860) – CORN AND COTTON PLANTERS

Henry Blair was born in Glen Ross, Maryland in 1807. He appears to have never been enslaved, due to his patent eligibility (enslaved people could not register patents with the United States government). Blair managed his own independent business as a commercial farmer near Glen Ross although he was unable to read or write. It is also worth noting that Henry Blair is the only inventor denoted as a “colored man” in the records of the US Patent Office.

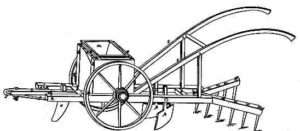

After finding success as a farmer, Blair proved himself a capable inventor. On October 14, 1834, Blair received his patent for his mechanical corn seed planter. Blair’s corn planter resembles a wheelbarrow with a chamber fixed to the bottom that disperses the seed. After the seed is dispersed, rakes attached to the back of the wheelbarrow drag over the seed to cover them with soil.

Blair’s corn planter resulted in more efficient crop planting and greater overall yield for farmers. According to an 1836 article from The Mechanics’ Magazine, Blair’s invention was conjectured to “save the labor of eight men.”

On August 31, 1836, Blair obtained a patent for his mechanical cotton planter. The device is essentially an adaptation of Blair’s corn planter optimized for cotton. The cotton planter also resembled a wheelbarrow, but it had two blades that split the earth while a cylinder located behind the blades dispersed the seeds in to the freshly ploughed grooves.

Blair’s inventions improved the productivity of corn and cotton agriculture.

DR. CHARLES DREW (1904-1950) – PRESERVATION OF BLOOD PLASMA

Born on June 3, 1904, in Washington, D.C. Drew grew up in the city. At Dunbar High School, his excellence in academics and athletics earned him an athletic scholarship to Amherst College in Massachusetts.

In 1929, he attended medical school at McGill University in Canada, where he studied with anatomy professor Dr. John Beattie. Drew developed his interest in blood storage just before he graduated in 1933. In 1935, Drew became a professor at Howard University’s medical school.

In 1938, the Rockefeller Foundation offered Drew a research fellowship at New York’s Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center to study blood. While there he discovered that plasma, a pale yellow liquid without the blood cells could be stored, preserved, and used in an emergency. Shortly after receiving his Doctor of Science, he was asked to direct a pilot program for collecting, testing, and distributing blood plasma in Great Britain. During the five-month program, Drew and his associates collected blood from over 15,000 people and gave about 1,500 transfusions.

Dr. Drew revolutionized medicine by inventing a technique for the long-term preservation of blood plasma, thus allowing the immediate and safe transfusion of blood plasma. Prior to his discovery, blood could only be stored for two days. Dr. Drew also discovered that everyone has the same type of plasma, regardless of blood type, making plasma transfusions universal.

With the success of the program, Drew gained international fame and was appointed director of the first American Red Cross Plasma Bank. During World War II, he recruited 100,000 blood donors for the U.S. Army and Navy. Their blood saved the lives of thousands of wounded soldiers. Ironically, the U.S. armed forces maintained a segregated blood donation system that refused to give blood from non-Whites to White soldiers. Drew denounced the policy, stating that there was no scientific evidence of difference based on race and resigned his position. He returned to Washington D.C. and became the head of Howard University’s Department of Surgery and later chief surgeon at Freedman’s Hospital. He was the first Black surgeon examiner of the American Board of Surgery.

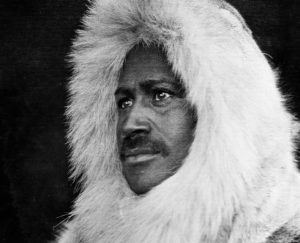

MATTHEW HENSON (1866-1955) – CO-DISCOVERER OF THE NORTH POLE

Matthew Alexander Henson was born, in Charles County, Maryland, the son of two freeborn Black sharecroppers. Henson lost his mother at an early age and his father a few years later.

At the age of 11, Henson left home to find his own way. After working briefly in a restaurant, he walked all the way to Baltimore, Maryland, and found work as a cabin boy on the ship Katie Hines. Its skipper, Captain Childs, took Henson under his wing and saw to his education, which included instruction in the finer points of seamanship. During his time aboard the Katie Hines, he also saw much of the world, traveling to Asia, Africa and Europe.

In 1884 Captain Childs died, and Henson found work as a clerk in a Washington, D.C. hat shop. It was there that, in 1887, he met Robert Edwin Peary, an explorer and officer in the U.S. Navy Corps of Civil Engineers. Impressed by Henson’s seafaring credentials, Peary hired him as his valet for an upcoming expedition to Nicaragua.

Shortly after returning from Nicaragua, Henson joined Peary again, for an expedition to Greenland. While there, Henson embraced the local Eskimo culture, learning the language and the natives’ Arctic survival skills over the course of the next year.

Their next trip to Greenland came in 1893, this time with a goal of charting the entire ice cap. Despite this perilous trip, the explorers returned to Greenland in 1896 and 1897, to collect three large meteorites they had found during their earlier quests, ultimately selling them to the American Museum of Natural History and using the proceeds to help fund their future expeditions.

Over the next several years, Peary and Henson made multiple attempts to reach the North Pole. Their 1902 attempt proved tragic, with six Eskimo team members perishing due to a lack of food and supplies. However, they made more progress during their 1905 trip. Backed by President Theodore Roosevelt and armed with a then state-of-the-art vessel that had the ability to cut through ice, the team was able to sail within 175 miles of the North Pole. Melted ice blocking the sea path thwarted the mission’s completion, forcing them to turn back.

The team’s final attempt to reach the North Pole began in 1908. Henson proved an invaluable team member, building sledges and training others on their handling. Of Henson, expedition member Donald Macmillan once noted, “With years of experience equal to that of Peary himself, he was indispensable.” While other team members turned back, Peary and the ever-loyal Henson trudged on. Peary knew that the mission’s success depended on his trusty companion, stating at the time, “Henson must go all the way. I can’t make it there without him.”

On April 6, 1909, Peary, Henson, four Eskimos and 40 dogs (the trip had begun with 24 men, 19 sledges and 133 dogs) finally reached the North Pole — or at least they claimed to have.

Triumphant when they returned, Peary received many accolades for his accomplishment, but — an unfortunate sign of the times — as a Black man, Henson was largely overlooked. And while Peary was lauded by many for his achievement, he and his team faced wide skepticism about allegedly reaching the North Pole due to a lack of verifiable proof. Decades after Peary’s death, however, navigational errors in his travel log surfaced, placing the expedition in all probability a few miles short of its goal.

Henson spent the next three decades working as a clerk in a New York federal customs house. He recorded his Arctic memoirs in 1912, in the book A Negro Explorer at the North Pole. In 1937, a 70-year-old Henson finally received the acknowledgment he deserved: The highly regarded Explorers Club in New York accepted him as an honorary member. In 1944 he and the other members of the expedition were awarded a Congressional Medal. He worked with Bradley Robinson to write his biography, Dark Companion, which was published in 1947.

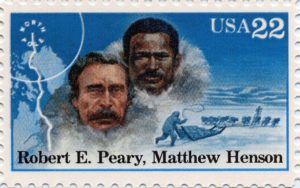

In 1986, Peary and Henson were honored on a commemorative stamp.

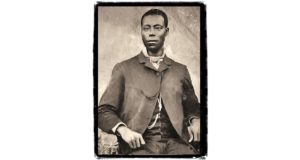

THOMAS JENNINGS (1791-1856) – DRY CLEANING

Thomas Jennings was a free man born in 1791 in New York City. In his early 20s he became a tailor. Jennings’ skills were so admired that people near and far came to him to alter or custom tailor items of clothing for them. Eventually, Jennings reputation grew such that he was able to open his own store on Church Street which grew into one of the largest clothing stores in New York City.

While running his business Jennings developed a dry-cleaning process called “dry-scouring.” Many of his customers complained of their clothes being ruined by stains so he began experimenting with cleaners and mixtures that would remove the stains without harming the material. On March 3, 1821, he became the first Black American to receive a patent for his process. He was 30 years old.

The patent to Jennings generated considerable controversy. Slaves at this time could not patent their own inventions; their effort was the property of their master. This regulation dated back to the US patent laws of 1793. The regulation was based on the legal presumption that “the master is the owner of the fruits of the labor of the slave both manual and intellectual.” Patent courts also held that slaves were not citizens and therefore could not own rights to their inventions. In 1861 patent rights were finally extended to slaves. Furthermore, the court said that the slave owner, not being the true inventor, could not apply for a patent.

Thomas Jennings, however, was a free man and thus was able to gain exclusive rights to his invention and profit from it. Jennings was a passionate abolitionist who used the first income from his invention to free the rest of his family from slavery and fund abolitionist causes.

Thomas L. Jennings’ Dry Scouring technique created modern day dry cleaning.

FREDERICK JONES (1893-1961) – TRUCK REFRIGERATION SYSTEMS

Frederick McKinley Jones was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on May 17, 1893 to a White father and Black mother. His mother deserted him when he was a young child. When Frederick was 7 years old, his father sent the young boy to live with a priest in Kentucky. [NOTE: Multiple accounts of Jones’ early childhood exist. This is one of various versions of the ages at which his parents died, and the age at which he went to and left the rectory. Facts of this period are inconclusive.]

At the age of 11, with minimal education under his belt, Jones left the rectory to fend for himself. He returned to Cincinnati and found work doing odd jobs, including as a janitor in a garage. By watching the mechanics as they worked on cars, and with an insatiable appetite for learning through reading, he developed a knack for automobile mechanics. He was so good, he was promoted to foreman of the shop. By age 19, he had built and driven several cars in racing exhibitions and became one of the most well-known racers in the Great Lakes region.

In 1912, he landed in Hallock, Minnesota, where he obtained a job doing mechanical work on a farm. Jones had talent for and an interest in mechanics. He read extensively on the subject in addition to his daily work, educating himself in his spare time. By the time he was twenty, Jones was able to secure an engineering license in Minnesota.

During World War I, he was a sergeant in the U.S. Army and served as an electrician, often called upon to make repairs to machines and other equipment. While serving, he rewired his camp for electricity, telephone, and telegraph service. After the war, he returned to the farm.

It was on the Hallock farm that Jones educated himself further in electronics. When the town decided to fund a new radio station, Jones built the transmitter needed to broadcast its programming. To make ends meet, Jones often aided local doctors by driving them around for house calls during the winter season. When navigation through the snow proved difficult, Jones attached skis to the undercarriage of an old airplane body and attached an airplane propeller to a motor. He was soon whisking doctors around town at high speeds in his new “snow machine.”

When one of the doctors he worked for complained that he had to wait for patients to come into his office for x-ray exams, Jones created a portable x-ray machine that could be taken to the patient. Unfortunately, like many of his early inventions, Jones never thought to apply for a patent. He watched helplessly as other men made fortunes off of their versions of the same device.

He also developed a device to combine moving pictures with sound. Local businessman Joseph A. Numero subsequently hired Jones to improve the sound equipment he produced for the film industry. Jones converted silent-movie projectors into talking projectors by using scrap metal for parts, and devised ways to stabilize and improve picture quality.

Jones continued to expand his interests in the 1930s. In 1939, Jones invented and received a patent for an automatic ticket-dispensing machine to be used at movie theaters. He later sold the patent rights to RCA.

He designed and patented a portable air-cooling unit (portable refrigeration units) that would allow trucks to transport perishable foods without spoiling. Forming a partnership with Numero, Jones founded the U.S. Thermo Control Company. During World War II, the need for a unit for storing blood serum for transfusions and medicines led Jones into further refrigeration research. For this, he created an air-conditioning unit for military field hospitals and a refrigerator for military field kitchens. As a result, may lives were saved. A modified form of his device is still in use today. By 1949, U.S. Thermo Control was worth millions of dollars.

Over the course of his career, Jones received more than 60 patents. While the majority pertained to refrigeration technologies, others related to X-ray machines, engines and sound equipment.

Jones was recognized for his achievements both during his lifetime and after his death. In 1944, he became the first Black American elected to the American Society of Refrigeration Engineers.

In 1991, President George H.W. Bush awarded the National Medal of Technology posthumously to Jones, presenting the award to his widow at a ceremony held in the White House Rose Garden. Jones was the first African American to receive the award, though he did not live to receive it. He was inducted into the Minnesota Inventors Hall of Fame in 1977.

ERNEST EVERETT JUST (1833-1941) – SCIENTIST

Born August 14, 1883 in Charleston, South Carolina, Just was only four years old when his father died. Due to mounting debt, his mother, Mary Just, and her children moved from Charleston to James Island, a community off the coast of South Carolina, to work in its phosphate mines.

In 1896, Just was sent to attend the high school of the Colored Normal Industrial, Agricultural & Mechanical College (later named South Carolina State University). Believing that he would receive a superior education by attending a college preparatory school in the North, Just enrolled in Kimball Union Academy in New Hampshire in 1900, the only Black student in the school.

During his university years at Dartmouth College he discovered an interest in biology after reading a paper on fertilization and egg development. He graduated as the sole magna cum laude student in 1907, also receiving honors in botany, sociology and history.

Just’s first job out of college was as a teacher and researcher at the traditionally all-Black Howard University. He obtained a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Chicago, where he studied experimental embryology and graduated magna cum laude.

Just also served as editor of three scholarly periodicals and, in 1915, won the NAACP’s first Spingarn Medal for outstanding achievement by a Black American. From 1920 to 1931, he was a Julius Rosenwald Fellow in Biology of the National Research Council — a position that provided him the chance to work in Europe after racial discrimination hindered his opportunities in the United States. During this time, Just penned many research papers, including the 1924 publication “General Cytology,” which he co-authored with respected scientists from Princeton University, the University of Chicago, the National Academy of Sciences and the Marine Biological Laboratory.

Just worked for many years at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. At the laboratory, Just realized that a doctorate in the sciences was key to his success, and he began a program of self-study at the University of Chicago, where he earned a doctorate in zoology in 1916. Just published fifty scientific papers in the areas of cytology, fertilization and early embryonic development, as well as two influential books, Basic Methods for Experiments on Eggs of Marine Mammals (1922) and Biology of the Cell Surface (1939).

Just pioneered many areas on the physiology of development, including fertilization, experimental parthenogenesis, hydration, cell division, dehydration in living cells, and ultraviolet carcinogenic radiation effects on cells. He believed that the conditions used for experiments in the laboratory should closely match those in nature; in this sense, he can be considered to have been an early ecological developmental biologist. His work on experimental parthenogenesis has broadly influenced modern evolutionary and developmental biology. His investigation of the movement of water into and out of living egg cells (all the while maintaining their full developmental potential) gave insights into internal cellular structure that is now being more fully elucidated using powerful biophysical tools and computational methods. These experiments anticipated the non-invasive imaging of live cells that is being developed today. Although Just’s experimental work showed an important role for the cell surface and the layer below it, the “ectoplasm,” in development, it was largely and unfortunately ignored. His primary legacy is his recognition of the fundamental role of the cell surface in the development of organisms. In his work within marine biology, cytology and parthenogenesis, he advocated the study of whole cells under normal conditions, rather than simply breaking them apart in a laboratory setting.

Just was the subject of the 1983 biography Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just by Kenneth R. Manning. The book received the 1983 Pfizer Award and was a finalist for the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography. In 1996, the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Just.

Since 2000, the Medical University of South Carolina has hosted the annual Ernest E. Just Symposium to encourage non-White students to pursue careers in biomedical sciences and health profession. In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Just on his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans.

CONCLUSION

The creation of Black History Month in 1976, by President Gerald Ford, was an attempt to recognize Black Americans who have made momentous contributions to America. He asked Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

Celebrating Black History Month each February is one way for Americans to express gratitude to members of the Black community who have given our country so much and whose achievements went unrecognized for so long. But I hope that we can honor on a daily basis the achievements of those whose names are included here, and whose research and inventions enhance our daily lives.