Combating Racism – In Sports

With the 2021 Olympic Games wrapping up today, I’ve watched more sports in the last two weeks than I have in the last two years. I revel at the mastery, courage, stamina, dedication, and determination of these international athletes, rooting primarily for the Americans.

For decades, Black parents have told their children that in order to succeed in the face of racial discrimination, they need to be “twice as good”: twice as smart, twice as dependable, twice as talented. They had to work twice as hard to get half as much. This advice can be found in everything from literature to television shows, to day-to-day conversation. A 2015 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research reveals that notion might be more than just a platitude.

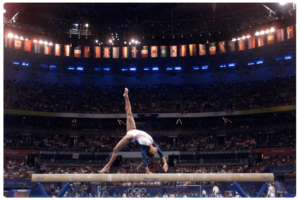

This pressure was most dramatically illustrated last week when Simone Biles, in an effort to hoist all that pressure off herself, withdrew from the American women’s gymnastics team and all individual competitions except the balance beam, saying she feels “like I have the weight of the world on my shoulders.” According to an article in The Washington Post, “A different kind of pressure follows Black women who achieve in traditionally White spaces.” The same can be said for all Black athletes.

The pressure on Black athletes to achieve is not just for themselves, but so that the path is easier for the next Black athlete who may follow in their footsteps. In a recent essay tribute to Black athletes by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, he mentioned Jackie Robinson, Bill Russell, and other significant Black athletes who were “like thick knots in the rope, each helping us all climb just a little faster and a little higher.”

Although I’ve written about the accomplishments of little known Black scientists and inventors, I haven’t focused on the many Black athletes who, in their own fields and in their own ways, overcame racism to build the ladder on which subsequent Black athletes could stand. They helped to break racial barriers and awaken America’s conscience. Some are less well known than others. Hence this newsletter.

TRACK AND FIELD

Wilma Rudolph (1940 – 1994)

Wilma Rudolph, born premature in June, 1940, overcame scarlet fever and infantile paralysis (polio) and her doctor’s diagnosis that she would never walk again, to go on to compete in track and field at the 1956 and 1960 Olympic Games. She won a bronze medal in the 200-meter dash and a bronze medal in the 4 x 100-meter relay at the 1956 Australia Olympics. In the 1960 Olympics in Rome, she won three gold medals in the 100- and 200-meter individual events and the 4 x 100-meter relay. She was acclaimed as the fastest woman in the world in 1960 and became the first American woman to win three gold medals in a single Olympiad.

As an Olympic champion in the early 1960s, Rudolph was among the most highly visible Black women in America and abroad. She became a role model for black and female athletes, having overcome a physical disability to become the fastest woman runner in the world, and her Olympic successes helped elevate women’s track and field in the United States.

Rudolph’s celebrity also caused gender barriers to be broken at previously all-male track and field events such as the Millrose Games. Rudolph is also regarded as a civil rights and women’s rights pioneer. You can read her autobiography, Wilma: The Story of Wilma Rudolph, which was published in 1977.

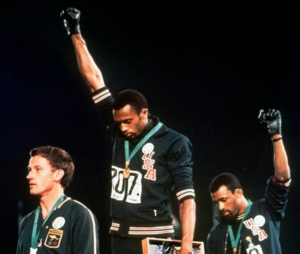

Tommie Smith and John Carlos (1944 – ) and (1945 – )

Tommie Smith was 24 years old in 1968 when he won the gold medal at the Mexico City Olympics running the 200-meter sprint in 19.83 seconds—the first time the 20-second barrier was officially broken. John Carlos finished third in that competition, winning the bronze medal. Tommie, a member of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), and Smith raised their black-gloved fisted hands on the victory stand in opposition to the racial discrimination they faced back home and in solidarity with those fighting for equality. The two men wore only black socks and no shoes onto the medal stand to represent Black poverty in America. In support, silver medalist Peter Norman of Australia joined the two Americans in wearing the round OPHR button on the medal stand. As a result of their action, Smith and Carlos were expelled from the Olympics, received death threats, and dealt with economic hardship. Smith’s journey to find purpose in the aftermath is the subject of a new documentary, “With Drawn Arms.”

HOCKEY

Willie O’Ree (1935 – )

Willie O’Ree became the first Black player in the National Hockey League (NHL) when he debuted with the Boston Bruins in January, 1958. Two years earlier, he had been blinded in his right eye when he was hit with a puck, a secret he kept from the NHL. He faced racist slurs including fans yelling “Go back to the South,” (O’Ree was born in Canada) and “How come you’re not picking cotton?” O’Ree was the only Black player in the NHL until Mike Marson was drafted by the Washington Capitals in 1974. In 1998 the NHL made O’Ree the NHL’s Diversity Ambassador, traveling across North America to schools and hockey programs to promote messages of inclusion, dedication and confidence in the NHL’s Hockey is for Everyone program. You can read more about O’Ree’s life in Willie O’Ree: The Story of the First Black Player in the NHL by Nicole Mortillaro.

TENNIS

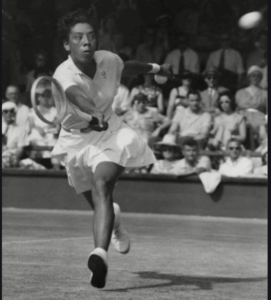

Althea Gibson (1927 – 2003)

Althea Gibson, the daughter of southern sharecroppers who worked a cotton farm, broke tennis’ color barrier in the 1950’s as the first Black entrant at Wimbledon in 1951. She won her first tournament at age 15, becoming the New York State Black girls’ champion and boxer Sugar Ray Robinson helped pay her travel expenses. Her first major singles title came in 1956 when she became the first Black American to win a Grand Slam title at the French Open; she won both Wimbledon and the U.S. Open in 1957-58, after which New York City gave her a parade. She won 11 Grand Slam titles: five in singles, five in doubles, and one in mixed doubles. More than 30 years passed before another Black woman, Zina Garrison, reached the Wimbledon final in 1990.

After she retired from tennis, Gibson integrated women’s golf, becoming the first Black woman to join the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) tour, playing in 171 tournaments from 1963-1977 without a title. But she faced racial discrimination since many hotels excluded people of color, and country club officials routinely refused to allow her to compete. She was often forced to dress for tournaments in her car because she was banned from clubhouses.

Gibson’s career ultimately opened doors for Katrina Adams, the first Black president and CEO of the U.S. Tennis Association, and Venus and Serena Williams, two Black sisters who have transformed the sport of tennis. Venus Williams wrote of Gibson, “I am honored to have followed in such great footsteps. Her accomplishments set the stage for my success.” Before her death she collaborated with Frances Gray on the book, Born to Win: The Althea Gibson Story, published in 2004.

NASCAR

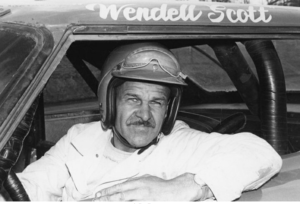

Wendell Scott (1921 – 1990)

Wendell Scott was the first Black American race car driver to win a race in the NASCAR Grand National Series. His father worked for wealthy white families as a driver and auto-mechanic and taught Wendell Scott about cars at a young age. Scott had a history of running moonshine whiskey and built and drove fast cars to escape the police. In May, 1952 he became the first Black American to drive in an official stock car race.

Scott tried many times to get into some official National Association for Stock Car Racing (NASCAR) races, but was turned down each time because of his race. Finally, he got into the NASCAR circuit by taking over the auto racing license from a white driver. He worked his way up to what is now known as the Sprint Cup Division, the top division in NASCAR. On December 1, 1962, he became the first Black American to win a rice in the Sprint Cup Division after coming in first at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida. Nevertheless, the second place finisher was declared the champion, until the Association corrected their error a few days later. In 1977, he was inducted into the National Black Athletic Hall of Fame.

According to Willy Ribbs, the first Black driver to race in the Indianapolis 500, “Wendell Scott showed Blacks in this country that there is opportunity, if you are willing to endure and pay the price. While his accomplishments were muzzled by NASCAR, he cracked an opening in a door that had been nailed shut.”

BASEBALL

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (1919 – 1972)

Jackie Robinson was the first Black American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) in the 20th century, breaking the color barrier that had existed since 1884, when Blacks were relegated to the Negro leagues. When he started at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, he forever changed the face of Major League Baseball.

By the end of his first season, Robinson had racked up 12 home runs, 29 steals and took home the Rookie of the Year award. During his 10-year MLB career, Robinson was an All-Star for six consecutive seasons from 1949 through 1954, and won the National League’s Most Valuable Player Award in 1949—the first Black player so honored. Robinson played in six World Series and contributed to the Dodgers’ 1955 World Series championship.

In his contract with the Dodgers, he agreed to turn the other cheek when he heard racial slurs or received threats of violence. Initially shunned by fans and his own teammates, he stayed true to his contractual agreement, despite having to stay in separate hotels while on the road with his team.

In 1997, MLB retired his uniform number 42 across all major league teams; he was the first professional athlete in any sport to receive that honor.

His success opened the floodgates for other Black Americans. Within the first five years of his career, another 150 Black players were signed to minor and major league teams.

After his 1956 retirement from baseball, he became an outspoken champion of civil rights and contributed significantly to the civil rights movement. He pushed baseball to use its economic influence to desegregate Southern towns and recruit more people of color into the leagues. He wrote, “The right of every American to first class citizenship is the most important issue of our time.”

Robinson also became the first Black vice president of a major American corporation, Chock Full o’Nuts. In the 1960s, he helped establish the Freedom National Bank, an African-American-owned financial institution based in Harlem, New York. In 1962, Robinson became the first Black American to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

GOLF

Charles Sifford (1922 – 2015)

Charlie Sifford was the first person of color to compete in Professional Golfers Association (PGA)-sanctioned events following the demise in 1961 of the “Caucasian-only” PGA membership clause. Throughout the world of golf, he was often compared to baseball’s Jackie Robinson, and went on to win PGA Tour events in 1967 and 1969 as well as the 1975 PGA Seniors’ Championship.

Sifford’s interest in golf began as a boy. As he made a living through caddying, he also had the opportunity to develop his golf skills. By age 13, he was shooting par golf. But his advancement was limited because of race discrimination in the Jim Crow era. Despite making significant strides in his career, he was the target of harassment and death threats prior to and following the abolishment of the “Caucasian-only” clause.

Sifford honed his game in the United Golf Association, a tournament circuit established in the mid-1920s by black golfers. He won the UGA’s biggest event, the National Negro Open, six times, including five successive years from 1952 to 1956. He was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 2004 and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2014.

Tiger Woods told The Associated Press in an email that he might never have taken up the game were it not for Sifford.

When Sifford died, Derek Sprague, president of the PGA of America, said “His love of golf, despite many barriers in his path, strengthened him as he became a beacon for diversity in our game. By his courage, Dr. Sifford inspired others to follow their dreams.”

BOXING

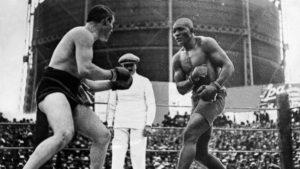

John Arthur Johnson (1878 – 1946)

“Jack” Johnson was the third of nine children born to former slaves and attended only five years in school. He was an American boxer who, at the height of the Jim Crow era, became the first Black American to win the world heavyweight boxing crown when he knocked out the reigning champ, Tommy Burns. Nicknamed “the Galveston Giant,” he held the title from 1908-1915. He has been widely regarded as one of the most influential boxers of all time.

In the early 1900’s, Johnson had made a name for himself in the Black boxing circuit and wanted to fight Jim Jeffries, who held the world heavyweight title. Jeffries refused to fight him. In December, 1908, Johnson got his chance at the title when the new champion, Tommy Burns, agreed to fight Johnson after being guaranteed $30,000 for the fight. After 14 rounds, police ended the fight and Johnson was named the winner.

On July 4, 1910, Johnson finally got his chance to fight Jeffries. More than 22,000 fans turned out for the match, which was called the “Fight of the Century.” After 15 rounds, Johnson was victorious, angering white boxing fans who hated seeing a Black man at the top of the sport. After he knocked Jeffries out, race riots exploded all over the country.

In total, Johnson’s professional record included 73 wins (40 of them knockouts), 13 losses, 10 draws, and 5 no contests.

In 1970, Johnson was portrayed by actor James Earl Jones in the film adaptation, The Great White Hope. Jones received an Oscar nomination for his performance. In 1990, Johnson was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and his life was documented in 2004 in Ken Burns’ Unforgivable Blackness.

FOOTBALL

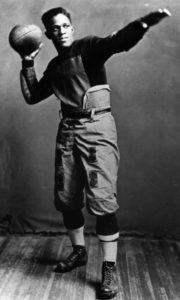

Frederick Douglas Pollard (1894 – 1986)

“Fritz” Pollard played halfback on the Brown University football team, which went to the 1916 Rose Bowl. He was the first Black player at Brown and the first Black American to play in the Rose Bowl.

Pollard turned pro in 1919 when he joined the Akron(OH) Pros following his World War I Army service. In 1920, the Pros joined the newly-founded American Professional Football Association, which later was renamed the National Football League (NFL). That season, he led the Pros to an undefeated (8-0-3) season to win the NFL’s first championship. Along with Bobby Marshall, he was the first Black American player in the National Football League in 1920. He was considered the most feared running back in the fledgling league.

During both his college and pro careers he was a target of multiple incidents of racial abuse. He was singled out for rough play and endured racial taunts that were customary for the time. The abuse was so severe that he had to be escorted to the field just before the kickoff. And during his pro career, he often had to change into his uniform in his car.

His spectacular runs, his elusive speed, along with his hard play earned the respect of all who played the game or saw him play.

In 1921, he earned another distinction by becoming the first Black head coach in NFL history when the Pros named him co-coach of the team. In 1923, after leaving Akron, he became the quarterback of the Hammond (IN) Pros—once again, the first of his color to play that position.

In 1934, a “gentleman’s agreement” was reached between the owners of the NFL teams to eliminate Black players from pro football. And no Black man played again until 1946. Pollard never stopped fighting for re-integration of the League. He even organized his own all-Black teams, the Brown Bombers and the Blackhawks, who played exhibition games against the all-white NFL starts. His Bombers were 19-0 in these matches.

In 1954, he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. In 2005, Pollard was posthumously inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The Fritz Pollard Alliance, a group promoting minority hiring throughout the NFL is named for Pollard.

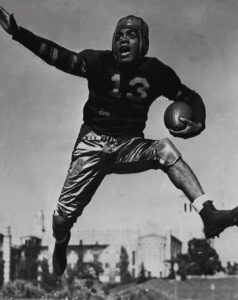

Kenneth Washington (1918 – 1971)

“The Kingfish,” as Kenny Washington was called, was an athletic phenomenon. As a left halfback for the UCLA Bruins, he set a college record of 3,206 yards for total offense over his career, won the Douglas Fairbanks trophy for the best college player in the U.S., and was named to an American college all-star team in August 1940. (He also played baseball for UCLA—averaging .454 in 1937 and .350 in 1938—where he was rated a better player than his teammate, Jackie Robinson.)

If he lived today, his path would have included an NFL draft pick. But in 1939 that wasn’t an option as the NFL had banned Black players six years earlier. When Washington graduated from UCLA, he coached football at his alma mater and joined the Los Angeles Police Department. From 1940-1945, he played for the Hollywood Bears of the Pacific Coast Professional Football League, considered a minor league of the highest level, and home to Black football stars.

When the Cleveland Rams moved to Los Angeles in 1946, the team wanted to play in the publicly-owned Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Since Black as well as White taxpayers had paid for the Coliseum’s construction, the team was pressed to be racially integrated. On March 21, 1946, the team signed Washington making him the first Black man to sign a contract with the NFL. Less than three months later, the team also signed Woodrow Wilson (“Woody”) Strode.

After retiring from football, Washington returned to the Los Angeles Police Department. He also worked as a part-time scout for the Los Angeles Dodgers and was chosen for film roles in Rope of Sand (1949), Pinky (1949), and The Jackie Robinson Story (1950).

BASKETBALL

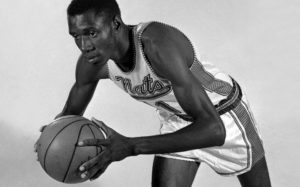

Earl Lloyd (1928 – 2015)

Before October 31, 1950, there were NO Black players in the National Basketball Association (NBA). But that night Horace “Bones” McKinney, coach of the Washington Capitols, sent a young Black man nicknamed “Big Cat” into the first game of the season. Earl Lloyd, at 6′ 7″ would go down in basketball history as a pioneer.

Lloyd honed his basketball skills on the playgrounds of inner city Washington, D.C. In 1947-48 Lloyd led West Virginia State University as the only undefeated team in the country. He led WVSU to two CIAA Conferences and Tournament Championships in 1948 and 1949.

According to Lloyd, unlike the situation for Jackie Robinson, “In 1950 in basketball, folks were used to seeing integrated college teams. There was a different mentality.” But according to the New York Times, along with the prejudice that existed in some cities, basketball owners were reluctant to sign Black players because they feared retaliation from Abe Superstein, owner of the all-Black Harlem Globetrotters.

Lloyd would only play in seven games with Washington before the team folded. After a stint in the U.S. Army, Lloyd signed with the Syracuse Nationals, where he and forward Jim Tucker became the first Black players to win an NBA championship. Lloyd finished his nine-year career with the Detroit Pistons. In 1968, Lloyd became the first Black assistant coach in the NBA, working for the Detroit Pistons.

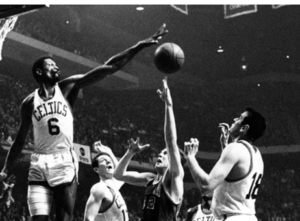

Bill Russell (1934 – )

Bill Russell led the University of San Francisco’s basketball team to back-to-back undefeated and national championship seasons in 1955 and 1956. His college success was followed by winning a gold medal at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne.

On April 30, 1956 he was acquired by the Boston Celtics in a trade from the St. Louis Hawks on the night of the NBA draft. With the 6’10” Russell at center, the Celtics were a nearly unstoppable force, winning 11 championships during his tenure, including the last two with him doubling as player and coach. The first title came in 1957, Russell’s rookie season. Boston lost to the Hawks the next season—primarily because Russell suffered an ankle injury in Game 3 of the finals—then won eight championships in succession. He was the linchpin of the most successful franchise in professional basketball history.

Russell was never more heroic than in the 1962 playoffs. To win the Celtics’ fourth consecutive title, Russell amassed 30 points and 40 rebounds. No other player had ever had more than 38 rebounds in a finals game. Russell also set a record for rebounds in a quarter (19). He became only one of two players to make more than 50 rebounds in a single NBA game when he grabbed 51 rebounds on February 6, 1960 against Syracuse.

Russell’s accomplishments were unprecedented. He won 11 titles, made 12 All-Star teams in just 13 seasons, and won five MVP awards.

Upon retirement, Russell coached the Seattle SuperSonics for four seasons and the Sacramento Kings for one. Russell wrote two autobiographies: Second Wind and Go Up For Glory. He was the first Black player to be inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame. In 1980, the Professional Basketball Writers Association of American named him the Greatest Player in the history of the NBA. He is revered as one of the greatest civil right advocates in American sports and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011.

GYMNASTICS

Dominique Dawes (1976 – )

Dominique made history when she won a bronze medal on the floor exercise for the American team in the 1996 Olympics. She had previously competed in the 1992 Barcelona Olympics and subsequently in the 2000 Olympics in Sydney. She was the first Black person of any nationality to win an individual Olympic medal in gymnastics and the only American gymnast to be a part of three medal-winning Olympic teams. as such, she set the stage for the boundary-breaking performances of Gabby Douglas in 2012 and Simone Biles in 2016.

Dawes now owns a gymnastics gym that emphasizes providing a healthy and supportive environment, and offers recreation and preschool gymnastics classes as well as a competitive team option. She has taken on advocacy roles as the president of the Women’s Sports Foundation (2004-2006) and in 2010 she was appointed co-chair of President Barack Obama’s Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition.

She earned the nickname “Awesome Dawesome” and has been inducted into the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame and the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame.

Gabrielle Douglas (1995 – )

Gabby Douglas is the 2012 Olympic all-around champion and the 2015 World all-around silver medalist. She was a member of the American teams at both the 2012 and 2016 Summer Olympics and a member of the American teams at the 2011 and 2015 World Championships, all of which won gold medals. She is the first Black American to become the Olympic individual all-around champion and the first U.S. gymnast to win gold medals in both the individual all-around and team competitions at the same Olympics. In December 2012, the Associated Press named her the Female Athlete of the Year.

But since competing in the 2016 Olympics in Rio, she has endured racial slurs, bullying and harassment, including being called “unpatriotic” for not putting her hand over her heart as the U.S. national anthem was played during a medal ceremony.

According to a statement by Simone Biles, “I remember when Gabby Douglas won, I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, if she can do it, then I can do it’.”

Douglas’ autobiography, Grace, Gold, and Glory: My Leap of Faith was published in 2012.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The athletes I’ve selected for this newsletter carried the burden of race and the hopes of the Black community on their backs. According to Abdul-Jabbar, winning isn’t just about trophies and rings, but about using these things as “currency to lift up the rest of the community.”

I close this essay with the closing words of Kareem Abdul-Jabarr’s essay:

“The heroism of Black athletes is a story of resilience. For many African American athletes—and the Black fans watching them—winning isn’t just crossing the finish line. It’s a symbol of every Black American hurdling and dodging the multitude of cultural, economic, educational, health, and other obstacles launched like grenades in their lane, meant to stop them. . . .We just have to remember that sports records come and go, but social justice can change lives forever.”