Combating Racism – Honoring Black History Month 2022 – Part 1

This week, February 1st will mark the beginning of Black History Month, honored every February since President Gerald Ford officially recognized the month in 1976. Originally created as Negro History Week in 1926 by Carter G. Woodson, by the late 1960’s, Negro History Week evolved into Black History Month. Since 1976, every U.S. President has officially designated February as Black History Month.

Every February, in recognition of Black History Month, we’re reintroduced to influential people in our history who have left marks in their respective industries. Their courage surpassed their fear and they held steadfast in their fight for justice and equality for the human race. Yet, while we’re constantly reminded of the Dr. Martin Luther Kings, Harriet Tubmans, and Rosa Parks of the past, there are many other Black individuals that often go unrecognized. Their paths were just as difficult and their fights just as courageous. In this and subsequent newsletters I’ll continue to focus on Black Americans who don’t often make headlines but who each transformed American life in a profound way.

In previous newsletters (12/13/20 and 12/20/20), I have honored the contributions of:

- Leonard C. Baily – patented a truss-and-bandage for hernia support and a folding bed

- Alice Augusta Bell – created first successful leprosy treatment

- Miriam Benjamin – invented a gong and signal chair, the forerunner to the signaling system on airplanes

- Henry Blair – invented corn and cotton planters

- Dr. Charles Drew – invented a technique for long-term preservation of blood plasma

- Matthew Henson – co-discoverer of the North Pole

- Thomas Jennings – developed dry-cleaning process

- Frederick Jones – created truck refrigeration systems and a device to combine moving pictures with sound

- Lewis H. Latimer – invented carbon filament for light bulbs

- Elijah McCoy – invented a lubricating cup for steam cylinders of locomotives, the first folding ironing board, and the first lawn sprinkler

- Jan Ernst Matzeliger – invented the lasting machine to stitch leather to the soles of a shoe

- Alexander Miles – created automatic elevator doors

- Benjamin Thornton Montgomery – invented the steam-operated propeller

- Garret A. Morgan – invented the gas mask and the three-way traffic signal

- Daniel Hale Williams – conducted the first open-heart forgery

- Granville T. Woods – invented the synchronous multiplex railway telegraph

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

As I did last year to honor Black History Month, I am honoring less familiar Black Americans who have made a significant contribution to American life. In this newsletter, I call your attention to two Black American members of the U.S. military who paved the way for others to follow. In subsequent newsletters during Black History Month, I’ll write about lesser-known Black Americans in other areas of American life.

Jesse LeRoy Brown (1926-1950)

Midshipman Jesse L. Brown, USN, Photographed at Naval Air Station, Jacksonville, Florida, October 1948, while serving as a Naval Aviation Cadet. (80-G-706531) Public Domain Image

Jesse LeRoy Brown was born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, the son of a sharecropper and schoolteacher. Brown was raised in different parts of Mississippi, depending on where his father secured employment. Brown was a determined young person, and he excelled in his schoolwork, graduating as salutatorian at his racially segregated Eureka High School. The flying bug caught him early; at the age of six, his father took him to an air show, and it determined the course of his life. He read about aviation constantly and learned that Black pilots did indeed exist (one of the pilots he learned about was Bessie Coleman, the first Black woman to earn a pilot’s license). At that point, no Black American pilots had yet been admitted to the U.S. military, and the brash young Brown even wrote a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt to question this state of affairs.

In 1944, Brown enrolled in the predominantly white college, Ohio State University, and supported himself in his studies by working as a janitor and boxcar loader for the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1945, he learned that the U.S. Navy was recruiting pilots for its V-5 light training program and he applied. Despite being told that he would never make it to the cockpit of a Navy aircraft, he persisted and was finally permitted to take the qualification exams. He endured five hours of written tests, followed by oral tests and a rigorous physical exam—making it through each round of eliminations with flying colors. Brown was admitted to the program because of the results of his entrance exams.

In 1947, he completed three phases of naval officer training in Illinois, Iowa, and Florida, including advanced flight training, despite repeatedly encountering racism from his instructors and peers. On October 28, 1948, at the age of 22, Brown became one of only six trainees, out of 100 who had started in the program, to win “Wings of Gold” and the first Black American man to complete Navy flight training. He received his Navy commission and became an officer in 1949. The newspapers paid attention to Brown’s progress, and his status as a commissioned naval officer made him a symbol of Black achievement in Black and White publications alike (he would be profiled in both The Chicago Defender and Life magazine).

In the summer of 1950, the Korean War broke out, and Brown’s squadron was transferred to the Pacific Fleet aboard the aircraft carrier USS Leyte.

Ensign Jesse L. Brown, USN, Takes the oath of office on board USS Leyte (CV-32), 26 April 1949. Administering the oath is the ship’s Commanding Officer, Captain William L. Erdmann. Lieutenant Commander E.D. Williams (center) is witnessing the ceremony. (80-G-707201)

Brown and his fellow pilots flew daily missions to protect troops threatened by China’s entrance into the war that November. On December 4, flying with his squadron of six planes over enemy targets, Chinese anti-aircraft fire forced his plane to crash land. He survived the crash, but was pinned under the debris of his plane. Brown’s wingman, Lt. Junior Grade Thomas Hudner Jr., disobeyed orders and crash landed his own aircraft and worked in vain to save him.

Although Brown died young, his story inspired many Black Americans to become military pilots. Furthermore, the dedication evinced by Hudner, a White man, for his squadron leader in the heat of war proved how irrelevant matters of race could be in the military, which had so often been a historically volatile arena for race relations.

Ensign Brown was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, and the Purple Heart. On April 13, 1951, President Harry S. Truman hosted a ceremony at the White House attended by Brown’s widow, Daisy, and the rest of his family as well as Lt. Thomas L. Hudner. In 1973, twenty-three years after his death, the frigate USS Jesse L. Brown was christened in his honor.

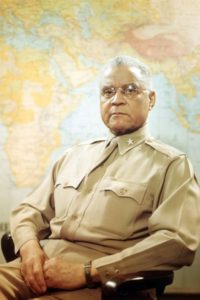

Benjamin O. Davis Sr. (1880-1970)

Photoquest/Getty Images

Benjamin O. Davis Sr., the first Black general in the U.S. Army and the U.S. military, was born in Washington, D.C., on July 1, 1877. He entered the military in July 1898 during the war with Spain as a temporary first lieutenant of the 8th U.S. Volunteer Infantry, an all-Black unit.

In June 1899, he enlisted as a private in the 9th Cavalry of the Regular Army. He then served as corporal and squadron sergeant major and in February 1901, he was commissioned a second lieutenant of Cavalry in the Regular Army. That spring he was posted overseas to serve in the Philippine-American War and assumed the dutires of a second lieutenant.

In 1915, Davis was assigned to Wilberforce College as Professor of Military Science and Tactics and to the traditionally Black Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Tuskegee, Alabama from 1920-1924.

Davis became commanding general of the 4th Cavalry Brigade at Fort Riley, Kansas in January 1941. About six months later, he was assigned to Washington, D.C. as an assistant in the Office of the Inspector General, where he also served on the Advisory Committee on Negro Troop Policies. From 1941-1944, he conducted inspection tours of Black soldiers in the U.S. Army stationed in Europe. While serving in the European Theater of Operations, Davis was influential in the proposed policy of integration using replacement units.

In 1947, he was assigned as a special assistant to the Secretary of the Army, during which time he represented the United States at Liberia’s centennial celebration.

In 1948, after 50 years of military service President Harry Truman oversaw a public ceremony honoring Brig. General Davis. Six days later, on July 26, 1948, President Truman issued Executive Order 9981 abolishing racial discrimination in the U.S. armed forces.

Among the honors he received are the Distinguished Service Medal, the Bronze Star Medal, Spanish War Service Medal, Philippine Campaign Medal, World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal, to name just a few.

In January 1997 the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in their Black Heritage Stamp series to honor the service and contributions of Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis. The photo was taken in France on August 8, 1944.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

While there have been many courageous Black Americans in the military, on this the eve of Black History Month, I want to honor these two trailblazers. Next week, more on Black American trailblazers.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Additional resources:

- “Benjamin Oliver Davis Sr. – The First African American General Officer in the Regular Army and in the U.S. Armed Forces”. United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007.

- Dwight, Margaret L.; Sewell, George A. (2009), “Mississippi Black History Makers”, Oxford, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 978-1-60473-390-7

- Fannin, Caroline M.; Gubert, Betty Kaplan; Sawyer, Miriam (2001), “Distinguished African Americans in Aviation and Space Science”, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-1-57356-246-1

- Jones, Jeffery (2019), “Benjamin O. Davis Sr., America’s First Black General: The Paradox of Racial Leadership and the Military Profession.” (PhD Dissertation, University of Memphis) excerpt.

- Kranz, Rachel, and Philip Koslow, eds. (Facts on File, 1999), “Biographical Dictionary of African Americans”

- Lee, Ulysses (1966), “The Employment of Negro Troops”. reprints 1986, 1990. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History

- MacGregor, M. J. (1981), “Integration of the Armed Forces”, 1940–1965, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, OCLC 7501802

- Smith, Larry (2004), “Beyond Glory: Medal of Honor Heroes in Their Own Words”, New York City, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-32562-1

- Taylor, Theodore (2007), “Flight of Jesse Leroy Brown”, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-59114-852-4

- Tillman, Barrett (2002), “Above and Beyond: The Aviation Medals of Honor”, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, ISBN 978-1-58834-056-6

- Weigley, Russell F. (1974), “Davis, Benjamin Oliver, Sr.” in John A. Garraty, ed. Encyclopedia of American Biography, pp. 256–257.

- Williams, Albert E. (2003), “Black Warriors: Unique Units and Individuals”, Haverford, Pennsylvania: Infinity Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7414-1525-7