Combating Racism – Honoring Women’s History Month – Part 1

Women’s History Month, which starts this coming Tuesday, March 1st, highlights the often-overlooked contributions of women in history, society, and culture. Women’s History Month traces its beginnings to the first International Women’s Day in 1911. The Sonoma, California school district organized a Women’s History Week in 1978, coinciding with March 8th—International Women’s Day. Hundreds of students participated in essay competitions and a parade was held in Santa Rosa. Then in 1980 President Jimmy Carter issued a presidential proclamation declaring the week of March 8, 1980 as National Women’s History Week. In 1987, Congress passed Public Law 100-9 proclaiming March as “Women’s History Month.” Women’s History Month has been observed every March since 1987.

This month I particularly want to honor the many American Black women who have broken gender and racial barriers as they made history and fought for justice, equality, and fair treatment. We are often reminded of the names of Maya Angelou, Mary McLeod Bethune, Shirley Chisolm, Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Phillis Wheatley, and more recently Stacey Abrams, Amanda Gorman, Kamala Harris, and Michelle Obama. Yet there are many other Black women whose paths were just as difficult and their fights just as courageous. These women have paved the way for other women and Blacks in general.

For Women’s History Month 2022 I will introduce 20 historic and contemporary lesser-known Black American women—civil rights activists, scientists, lawyers, doctors, directors—women who have blazed trails for others to follow.

In previous newsletters, I have written about these less familiar Black women, including:

- Aesha Ash – first Black ballerina in the New York City Ballet, organized the Swans Dream Project to present an alternative view of Black women to young girls;

- Alice August Ball – chemist who discovered the cure for leprocy;

- Daisy Bates – started The Arkansas Weekly newspaper and organized the Little Rock Nine who integrated Central High School in Little Rock;

- Miriam Benjamin – inventor of the Signal chair, the forerunner of signals used to call flight attendants on airplanes and to signal pages in the House of Representatives;

- Aurelia Browder – the lead plaintiff in Browder v. Gayle in which the Supreme Court ruled that segregated buses violated the Fourteenth Amendment;

- Mary Fair Burks – founded the Women’s Political Council (WPC) focusing on promoting civic involvement, increasing voter registration and lobbying to address racist policies;

- Beatrice Morrow Cannady – editor and publisher of The Advocate Oregon’s largest Black newspaper; co-founder of the Portland, Oregon chapter of the NAACP;

- Claudette Colvin – first to challenge discrimination in the Montgomery Alabama bus system at age 15 (before Rosa Parks);

- Jarena Lee – first authorized female preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church

- Mary Mahoney – first licensed Black nurse in the U.S. and champion of women’s rights;

- Mary Jane Patterson – pioneer in Black education;

- Harriet Forten Purvis – abolitionist and first generation suffragist; formed the first biracial women’s abolitionist group, the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society;

- Jo Ann Robinson – president of the Women’s Political Council (WPC), established the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to boycott racial segregation on Montgomery City busses, helped sustain the 381-day boycott;

- Maria Miller Stewart – worked for the abolition of slavery in the Massachusetts General Colored Association, wrote for William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator; and

- Madam C. J. Walker – inventor of hair care products, entrepreneur, philanthropist, political and social activist, and the first female self-made millionaire in America.

SADIE TANNER MOSSELL ALEXANDER (1898-1989)

Photo: Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

Sadie Tanner Mossell was born in 1889 in a house in Philadelphia owned by her uncle, the artist Henry Osawa Tanner. Her parents separated when she was a year old. Traveling between Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. where her uncle lived, during her elementary and middle school years, she never finished a full term of school during that time. When she became of high school age, her mother left her in Washington, D.C. to complete her education.

She attended the legendary all-Black M Street High School (now Dunbar High School) where students were exposed to talks by “living examples of what was possible if we applied our ability”—Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Coleridge Taylor, and Mary Church Terrell. Despite her desire to attend Howard University, her mother insisted she return to Philadelphia and attend the University of Pennsylvania. There she confronted blatant racial discrimination from White classmates, faculty and staff. She was unable to check books out of the library, and unable to get a hot meal either on campus or in the immediate neighborhood. No lunch counter in the University area served Black students and she was sometimes greeted with the “N” word. Many of the classes she wanted were barred to women.

During her sophomore year, she urged the provost of the university to use his influence to declare eating places that refused Penn students to be off bounds for Penn students. She also asked that the University provide a venue for both Black and poor students where they could get a hot lunch meal. She was turned down, but this was her first entry into civil rights activism.

Despite earning Distinguished in all her classes, she was not awarded a Phi Beta Kappa key, an honor she deserved. In June 1921 at the age of 32, Sadie Mossell became the first Black person in the United States to earn a Ph.D. in Economics. Her dissertation was titled, “The Standard of Living among One Hundred Negro Migrants Families in Philadelphia, 1921.

On November 29, 1923, Sadie Tanner Mossell married Raymond Pace Alexander, the son of slaves who had established a law practice in Philadelphia.

The following year, she was the first Black woman to enroll in the School of Law at Penn. A dean at the law school lobbied against her being selected to join the university’s law review. She persevered and made law review anyway in her first year, becoming the first Black woman to achieve this distinction. Alexander passed the Pennsylvania bar and in 1927 became the first Black woman to practice law in the state. She and her husband managed a private law firm until 1959 when she opened her own firm and her husband became a Philadelphia judge.

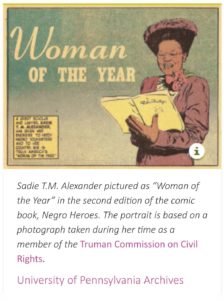

In addition to her legal career, she was an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League, and other service organizations devoted to improving race relations. Alexander’s accomplishments were chronicled by the Urban League in “Negro Heroes,” its comic book showcasing influential Black Americans, where she was named ‘Woman of the Year’ in 1948.

U.S. presidents took notice. In 1947, President Harry Truman named her to his Committee on Civil Rights, whose report became a blueprint for the civil rights movement. Some 30 years later, President Jimmy Carter appointed her chair of the White House Conference on Aging, which sought to address the social and economic needs of the elderly.

By the time of her 1989 death at 91, Alexander had been awarded seven honorary degrees and had taken her rightful place as a revered champion of equal rights for all.

ELLA BAKER (1903-1986)

Afro Newspaper/Gado via Getty Images

Ella Baker is another important civil rights activist you may not have heard of. She was born December 13, 1903, in Norfolk, Virginia, and raised on the same land her grandparents worked as enslaved people.

Baker’s strength and resilience came directly from her family. She developed a sense for social justice early on when listening to her grandmother’s stories about life under slavery, including being whipped for refusing to marry the man her slave owner chose for her. Her grandmother’s pride and resilience in the face of racism and injustice inspired Ms. Baker throughout her life.

She spent her early life challenging school rules that she felt were unfair. In 1927, after graduating from Shaw University as valedictorian, Baker moved to New York City to begin work as a social activist. In 1930 she joined the Young Negros Cooperative League, whose purpose was to develop Black economic power through collective planning. She became their national director.

In 1940 she joined the NAACP, starting as a field secretary and eventually becoming director, from 1943-1946. Traveling through the South, Baker recruited members, raised money, and helped to organize local chapters. In 1955, she co-founded the organization In Friendship to raise money to fight against Jim Crow laws in the deep South.

Baker believed that the power of the NAACP should come from the bottom up. She made sure to get to know as many of the people in the South as she could. She slept on their couches, ate in their homes, and earned their trust. She was building a network of people who could help with the civil rights movement.

In 1957 Baker made her way to Atlanta to be a part of Martin Luther King’s new organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Specifically, she worked on the campaign, called the Crusade for Citizenship, to help enforce voting rights for Blacks. The crusade was sparked by the civil rights bill then pending in Congress.

On February 1, 1960, a group of Black college students from North Carolina A&T University staged a sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, where they had been denied service. Baker left the SCLC to assist new student activists in organizing themselves. She viewed the young, emerging activists as a resource and an asset to the movement. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was created.

The SNCC joined forces with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and organized the Freedom Rides in 1961. The Freedom movement continued into 1964 with the Freedom Summer and its hope to register as many Black voters as possible. Baker and many of her contemporaries believed that voting was one key to freedom. (Today that is still the case.)

With Ella Baker at the helm, the SNCC became one of the biggest forces for human rights in the country. Baker’s influence lasted for the rest of her life, until her death on her 83rd birthday, Dec 13, 1986.

The nickname she was given in her life was “Fundi,” a Swahili word that means a person who teaches a craft to the next generation. The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights in Oakland, California was established to build on her legacy.

DR. PATRICIA BATH (1942-2019)

Patricia Bath was born in November, 1942 in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood to Rupert Bath, the first Black motorman for the New York City subway system, and Gladys Bath, a housewife and domestic worker who used her salary to save money for her children’s education. Bath was encouraged by her family to pursue academic interests. Her father, a former Merchant Marine and an occasional newspaper columnist, taught Bath about the wonders of travel and the value of exploring new cultures. Her mother piqued the young girl’s interest in science by buying her a chemistry set.

At age 16, she became one of only a few students to attend a cancer research workshop sponsored by the National Science Foundation. The program head, Dr. Robert Bernard, was so impressed with Bath’s discoveries during the project that he incorporated her findings in a scientific paper he presented at a conference. The publicity surrounding her discoveries earned Bath the Mademoiselle magazine’s Merit Award in 1960.

After graduating from high school in only two years, Bath headed to Hunter College, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in 1964. She then attended Howard University to pursue a medical degree. Bath graduated with honors from Howard in 1968, and accepted an internship at Harlem Hospital shortly afterward. The following year, she also began pursuing a fellowship in ophthalmology at Columbia University. Through her studies there, she discovered that Blacks were twice as likely to suffer from blindness as other patients, and eight times more likely to develop glaucoma. Her research led her to develop a community ophthalmology system, which increased the amount of eye care given to those who were unable to afford treatment.

In 1973, Bath became the first Black American to complete a residency in ophthalmology at New York University. She moved to California the following year to work as an assistant professor of surgery at both Charles R. Drew University and the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1975, she became the first female faculty member in the Department of Ophthalmology at UCLA’s Jules Stein Eye Institute.

In 1976, Bath co-founded the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness, which established that “eyesight is a basic human right.” By 1983, she had helped create the Ophthalmology Residency Training program at UCLA-Drew, which she also chaired, becoming, in addition to her other firsts, the first woman in the nation to hold such a position.

In 1981, Bath began working on her most well-known invention: the Laserphaco Probe (1986). Harnessing laser technology, the device created a less painful and more precise treatment of cataracts. She received a patent for the device in 1988, becoming the first Black female doctor to receive a patent for a medical purpose. She also holds patents in Japan, Canada and Europe. With her Laserphaco Probe, she helped restore the sight of individuals who had been blind for more than 30 years.

Bath retired from her position at the UCLA Medical Center in 1993 and became an honorary member of its medical staff. That same year, she was named a “Howard University Pioneer in Academic Medicine.”

Among her many roles in the medical field, Bath was a strong advocate of telemedicine, which uses technology to provide medical services in remote areas.

Bath died in May 2019 in San Francisco, California.

JANE BOLIN (1908-2007)

Jane Matilda Bolin was born in Poughkeepsie, New York in April, 1908 to an interracial couple. Her father was an influential attorney who headed the Dutchess County Bar Association and cared for the family after his wife died during Bolin’s early childhood. Bolin grew up admiring her father’s leather-bound books while recoiling at photos of lynchings of Black southerners in the NAACP magazine, The Crisis.

Bolin was a superb student who graduated from high school in her mid-teens. Wanting a career in social justice, she went on to enroll at Wellesley College, after being denied admission to Vassar College as it did not accept Black students at that time. Though facing overt racism and social isolation, she graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1928 and was officially recognized as one of the top students of her class. She then attended Yale Law School, where shse was the only Black student and one of only three women. Despite contending with further racial hostilities, she graduated in 1931, becoming the first Black woman to earn a law degree from the institution.

Bolin worked with her family’s practice in Poughkeepsie for a while before accepting a job in the New York City Corporation Counsel’s office. In 1933, she married attorney Ralph E. Mizelle and relocated to New York. (Mizelle would go on to become a member of President Franklin Roosevelt’s Black Cabinet.) After losing her campaign for a state assembly seat on the Republican ticket in 1936, she accepted a job in the New York City Corporate Counsel’s Office, creating another landmark as the first Black woman to hold that position.

In July 1939, New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia appointed her a family court judge. As the first Black female judge in the country, she made national headlines. For the compassionate Bolin, the job was a good fit.

As a judge in Family Court, Bolin was a thoughtful, conscientious force taking great care when it came to the plight of children. She was an activist for children’s rights and education. She didn’t wear judicial robes in court to make children feel more at ease and committed herself to seeking equal treatment for all who appeared before her, regardless of their economic or ethnic background.

She changed segregationist policies that had been entrenched in the system, including skin-color based assignments for probation officers. Additionally, Bolin worked with first lady Eleanor Roosevelt in providing support for the Wiltwyck School, a comprehensive, holistic program to help eradicate juvenile crime among boys.

She was a legal advisor to the National Council of Negro Women; she served on the boards of the NAACP, the National Urban League and the Child Welfare League.

She received honorary degrees from Tuskegee Institute, Williams College, Hampton University, Western College for Women and Morgan State University.

Bolin faced personal challenges, as well. Her first husband died in 1943, and she raised their young son, Yorke, for several years on her own. She remarried in 1950 to Walter P. Offutt Jr.

Though she preferred to continue, Bolin was required to retire from the bench at the age of 70, subsequently working as a reading instructor in the New York City Public Schools and served on the New York State Board of Regents.

She died in Long Island City, Queens, New York, on January 8, 2007, at the age of 98, having shattered multiple glass ceilings and broken barriers of race and gender as the first Black American woman to achieve many accomplishments.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Watch for next week’s newsletter when I share the biographies of four more amazing Black women.