Combating Racism – Honoring Women’s History Month – Part 3

This week’s newsletter is devoted to the first Black woman aviator and lesser known civil rights activists. These women’s names are part of my tribute to 2022’s Women’s History Month. I know this newsletter is long, but I had to honor each of these amazing women and tell their stories.

BESSIE COLEMAN (1892-1926)

Fotosearch via Getty Images

Bessie Coleman was born in a one-room shack in Atlanta, Texas in 1892 and grew up in a world of poverty and discrimination. Her home was one county over from Paris, Texas, where Whites lynched at least nine Black men between 1890 and 1920. Blacks were barred from voting through literacy tests, poll taxes, economic reprisals and terrorism. They couldn’t ride in railway cars with White people nor use public facilities set aside for Whites.

When Bessie first went to school at the age of six, it was to a one-room wooden shack, a four-mile walk from her home. Often there wasn’t paper to write on nor pencils to write with. An intelligent young girl, she attended school faithfully and was active in her Baptist church – that is, when she was not needed in the cotton fields to help her large family survive (there were 13 Coleman children altogether). She worked as a laundress to save money to attend college in Oklahoma, but her money ran out after only one semester.

Hoping for better things, she moved north to Chicago to stay with her older brother. Although she found life there difficult, with work as a manicurist neither lucrative nor fulfilling, she overheard and was entranced by the stories of pilots who had recently returned from the airfields of World War I. She was also spurred on by her brother, who taunted her with claims that French women were superior to Black American women because they could fly. She made up her mind to be a pilot.

In 1918, except for the occasional wealthy socialite, female pilots were rare and Black female pilots were non-existent. Coleman was stonewalled by sexism and racism from American pilots who scoffed at her desire to fly. Hearing of her woes, Black newspaperman Robert Abbott, the publisher of The Chicago Defender, financed her trip to Paris in November 1920, where her race and gender were not impediments, and Coleman trained with some of the best pilots in Europe. Despite being the only Black person in her class, she was treated with respect and earned her international pilot’s license by 1921. When she returned to America, she became a minor celebrity almost overnight. The Air Service News called her “a full-fledged aviatrix, the first of her race.”

In the early 1920s, commercial aviation was still in its infancy, so most active fliers were stunt fliers who performed at air shows. Coleman took to the air show circuit, where she was a big hit. Nicknamed “Queen Bess,” Coleman was known for her daredevil aerial tricks, and her race and her gender became a selling point instead of a liability. Over the following years, Coleman used her position of prominence to encourage other Black Americans to fly. She also made a point of refusing to perform at locations that wouldn’t admit Blacks.

For five years, she barnstormed around the country, making a good living, but one filled with risks; in 1923, she ended up in the hospital with a broken leg when her plane crashed from mechanical failure.

A more serious mechanical failure led to Coleman’s premature demise in 1926. She purchased a replacement plane for the one she’d lost in 1923. The plane had mechanical problems and was in desperate need of an overhaul, but William Wills, her co-pilot, and Coleman unwisely took it up on April 30th to survey the ground for the parachute jump that Coleman planned for the next day. The plane failed once again, but this time it could not be piloted safely to the ground; Wills was killed on impact, and Coleman, who had not been wearing a seatbelt so she could look at the landscape over the side of the plane, was pitched from her seat and died instantly.

For a number of years starting in 1931, Black pilots from Chicago instituted an annual fly-over of her grave. In 1977, a group of Black American women pilots established the Bessie Coleman Aviators Club. And in 1992, the U.S. Postal Service issued a Bessie Coleman stamp.

Coleman had hoped to inspire other young African Americans to take to the skies by establishing a flight school. Her dream to start a school would never be realized, but by being the first Black American woman to fly, she inspired countless young men and women to do the same, including Jesse LeRoy Brown.

ANNA ARNOLD HEDGEMEN

Source: Bettmann / Getty

Born in Marshalltown, Iowa, Anna Arnold was raised in Anoka, Minnesota, where her family was the only Black one in the small town. Her family was an active part of the community and she never felt different while growing up.

Arnold began shattering glass ceilings in 1918 when she became the first Black student at Hamlin University, a Methodist College in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Four years later, she became the university’s first Black graduate, earning a B.A. degree in English. While in college, she heard W.E.B. DuBois speak, which inspired her to succeed as an educator.

Arnold briefly taught at Rust College, a Black school in Holly Springs, Mississippi, before becoming disillusioned by segregation in the south and deciding to fight for its end.

For the next twelve years, Arnold worked on and off with the YMCA. In 1933, she became the executive director of the Black branch in Philadelphia. Moving to New York in 1934 to marry Merritt A. Hedgeman, she began working with the city’s Emergency Relief Bureau. The Bureau had only recently begun to hire Black supervisors, and Hedgeman served as its first consultant on racial problems. In addition to serving the city’s Black community, Hedgeman also worked with its Jewish and Italian constituents. She stayed with the ERB until 1937 when it became the Department of Welfare. She resigned and accepted a position as director of the Black branch of the Brooklyn YWCA. While in the position she organized a citizen’s coordinating committee to seek provisional appointments to the Department of Welfare for Black constituents. The committee secured the first 150 appointments the city had ever given to the Black community. Hedgeman was also able to expand employment opportunities for Black clerks in Brooklyn department stores. Her stay with the Brooklyn YMCA was cut short after the central board viewed some of her tactics, i.e. picket lines and challenging the old guard leadership, as too militant.

In 1944, A. Philip Randolph offered Hedgeman a job as executive director of the National Council for a Permanent Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC). She accepted the position believing that permanent legislation was needed to outlaw discrimination in employment. After a major legislative drive in 1946 failed, Hedgeman resigned to become dean of women at Howard University.

In 1948, Congressman William L. Dawson, vice president of the Democratic National Committee, asked Hedgeman to join Harry Truman’s presidential campaign. Hedgeman became the campaign’s executive director of the national citizen’s committee. She was tasked with raising funds from Black Americans. After the election, Hedgeman received a patronage appointment as assistant to the administrator of the Federal Security Agency, which later became the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. On February 12, 1949, she was sworn in as the first Black American to hold a position in the Federal Security Agency.

On January 1, 1954, Hedgeman became the first Black woman to hold a mayoral cabinet position in the history of New York City. She served under Robert F. Wagner as a mayoral assistant. She was responsible for eight city departments, acting as liaison with the mayor. She also gave speeches, and represented the mayor at conferences and conventions. Hedgeman stayed in the position until 1958. Growing increasingly frustrated with the city’s lack of response to Black concerns, she accepted a position as a public relations consultant for the Fuller Products Company. When S. B. Fuller purchased the New York Age, the nation’s oldest Black newspaper, Hedgeman was asked to serve as associate editor and columnist. Due to dwindling circulation, the paper ceased production in 1960.

In February 1963, Hedgeman played an instrumental role in conceptualizing the 1963 March on Washington. A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin called for a march for job opportunities to be held in October 1963. Martin Luther King Jr. was planning a July march to pressure public opinion on a strong civil rights bill. Hedgeman suggested that they combine efforts into a March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom to be held in August 1963. She was the only woman on the organizing committee. When she realized that no women were slated to speak, she protested the minimal recognition of women and persuaded the male dominated committee that this oversight was a mistake. As a result, Daisy Bates was invited to speak. As plans for the march were taking shape, Hedgeman was appointed by the National Council of Churches (NCC) to serve as coordinator of its newly formed Commission on Religion and Race. The purpose of the commission was to mobilize resources for Protestant and Orthodox churches to work against racial injustice in American life. She was asked to help mobilize thirty thousand white Protestant church leaders to march. While with the NCC, she worked to ensure the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

In 1964, she published her memoir, The Trumpet Sounds: A Memoir of Negro Leadership. She also published Gift of Chaos: Decades of American Discontent (1977) and many articles for numerous organizations.

Though Hedgeman has yet to become a household name, she has received numerous honors, including the Frederick Douglass Award from the New York Urban League; the National Human Relations Award from the State Fair Board of Texas; and awards from the Schomberg Collection of Negro Literature and the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO). Hedgeman received citations from the NAACP, the SCLC, the National Council of Negro Women, and United Church Women. Hamlin University awarded her an honorary doctorate in 1948. The New York State Conference on Midlife and Older Women awarded her the “pioneer woman” award in 1983.

Anna Arnold Hedgeman passed away at the Greater Harlem Nursing home on January 17, 1990. She worked for social justice for 70 years but has been mostly forgotten. There is now a Hedgeman Center for Student Diversity Initiatives at Hamline University and a scholarship in her name. Her legacy should inspire the next generation of change makers to continue to shatter glass ceilings despite the trials and tribulations they will endure.

DOROTHY HEIGHT (1912-2010)

Dorothy Irene Height was born on March 24, 1912 in Richmond, Virginia. Her family later moved to Rankin, Pennsylvania where she attended racially integrated schools and excelled as a student. While in high school, she became socially and politically involved in anti-lynching campaigns. She graduated from Rankin High School in 1929.

Height eventually received a scholarship to attend college. In 1929, she was admitted to Barnard College but was not allowed to attend because the school did not admit Blacks. Instead, Height went on to graduate from New York University where she received a bachelor’s in education and master’s in psychology. Her first job was as a social worker in Harlem, New York.

Height was appalled to learn that her race barred her from swimming in the pool at the central YWCA branch. She later joined the staff of the Harlem YWCA. In no time, Height became a leader in the local organization. She created diverse programs and was instrumental in the integration of all YWCA centers in 1946.

During a chance encounter with Black leader Mary McLeod Bethune, Height was inspired to begin working with the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW). There, she focused on ending the lynching of Blacks and restructuring the criminal justice system. In 1957, she became the fourth president of the NCNW. Under her leadership, the NCNW supported voter registration in the South, and financially aided several civil rights activists throughout the country. Height was president of NCNW for 40 years.

The increasing momentum of the civil rights movement prompted the YWCA’s National Board to allocate funds to launch a country-wide Action Program for Integration and Desegregation of Community YWCAs in 1963. Height took leave from her position as Associate Director for Training to head this two-year Action Program. At the end of that period, the National Board adopted a proposal to accelerate the work “in going beyond token integration and making a bold assault on all aspects of racial segregation.” It established an Office of Racial Integration (renamed Office of Racial Justice in 1969) as part of the Executive Office. Height became its first Director. Shortly before she retired from the YWCA in 1977, Height was elected as an honorary national board member, a lifetime appointment.

Height’s prominence in the Civil Rights Movement and unmatched knowledge in organizing, meant she was regularly called to give advice on political issues. Eleanor Roosevelt, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Lyndon B. Johnson often sought her counsel.

In 1963, Height, along with other civil rights activists, organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Although she played a role in the march, she was not invited to speak. In fact, originally no women were included on the program at all. Height and Anna Arnold Hedgeman persuaded the other organizers to allow a woman to speak. Despite the apparent gender discrimination in the Civil Rights Movement, Height continued working on the front lines. In his autobiography, civil rights leader James Farmer noted that Height’s role in the civil rights movement was ignored by the press due to sexism.

Also during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Height organized “Wednesdays in Mississippi” which brought together Black and White women from the North and South to engage in dialogue about relevant social issues and work against segregation.

In addition to her work in the United States, Height traveled extensively. She served as a visiting professor at the University of Delhi, India and with the Black Women’s Federation of South Africa. For all her efforts during the Civil Rights Movement, Height was awarded and recognized by many organizations. In 1989, she received the Citizens Medal Award from President Ronald Reagan and in 2004, Height was honored with the Congressional Gold Medal. The same year, Height was inducted into the Democracy Hall of Fame International. She also received an estimated 24 honorary degrees.

On April 20th, 2010, Height passed away at the age of 98. Her funeral was held at Washington National Cathedral where President Barack Obama referred to her as “the godmother of the Civil Rights Movement.” Shortly after her death, Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes and Mayor Vincent Gray renamed a historic postal office the Dorothy I. Height Post Office. This honor made Height the only Black woman to have a federal building in Washington, D.C. named after her.

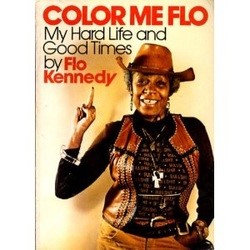

FLO KENNEDY (1916 – 2000)

Duane Howell via Getty Images

Florynce Rae “Flo” Kennedy was born in Kansas City, Missouri in February 1916. Her father worked as a Pullman porter and waiter, and later owned a taxi business. Both parents valued education and instilled the view that authority and respect needed to be earned. She was taught that, if she didn’t believe in something an authority figure told her to do, she didn’t have to do it. Florynce got her determined attitude from her father. When he bought a house in a mainly White neighborhood, he had the strength to fend off the Ku Klux Klan.

In her autobiography, Color Me Flo, Kennedy describes the altercation. “They stood on the sidewalk … and said they wanted to see our daddy. When Daddy came out, they told him, ‘You have to get out of here by tomorrow.’ [Daddy] brought his gun … out with him and said, ‘Now the first foot that hits that step belongs to the man I shoot. And then after that you can decide who is going to shoot me.’ They went away and they never came back.”

Although Kennedy graduated top of her class from Lincoln High School in Kansas City, in 1934, she delayed going to college. She went into business with her sisters opening a hat shop, and worked at a variety of other jobs, including operating elevators and singing on a radio show. Shortly thereafter, when a local Coca-Cola bottling facility refused to hire Black truck drivers, Kennedy organized a boycott—her first foray into social activism.

In 1942, Kennedy and her sister Grayce moved to New York City, where Flo began attending Columbia University in 1944. Even though she was encouraged to become a teacher, Kennedy graduated four years later with honors and a bachelor’s degree in pre-law.

Kennedy applied to Columbia Law School in 1948, but was initially denied admission by the dean. When she confronted him, believing the denial was based on her race and threatening to sue, the dean assured her that race was not the issue, but instead it was her gender. To Kennedy, neither discrimination would stand, and eventually Columbia changed its decision and admitted her. Flo Kennedy was one of eight women in her class, and in 1951 became only the second Black woman to graduate from Columbia Law School (the first was Elreda Alexander in 1945). After passing the New York Bar in 1952, Kennedy worked as a clerk in a Manhattan law firm, then opened her own private practice in 1954.

With her growing desire for civil rights and corporate accountability, Kennedy took on some high profile legal clients, such as civil rights activist H. Rap Brown. In 1969, she assisted in representing several Black Panther members who were charged with conspiracy to blow up stores in New York City. They were acquitted in 1971 after the longest political trial in New York’s history.

Taking on discrimination by recording company behemoths, Kennedy represented the estates of jazz legends Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker that were suing to recover withheld royalties and sales. The racism she encountered in the courts and in these cases began a serious disenchantment with the practice of law. She began to doubt her ability to work within the justice system to accomplish social change.

In her cowboy hat, pants, and pink sunglasses, Kennedy gained a reputation as a flamboyant activist who stood up to authority and did not care what people said about her. She has been quoted as saying, “My parents gave us a fantastic sense of security and worth. By the time the bigots got around to telling us that we were nobody, we already knew we were somebody.”

In the 1960s, Kennedy broadened her scope to include political involvement and battling oppression in a variety of arenas—racism, sexism, abortion rights, civil rights, and consumer protection. She led boycotts of large corporations, including picketing the Colgate-Palmolive building in New York, leading protests at CBS headquarters, and participating in anti-Vietnam War and pro-liberation initiatives organized by Youth Against War and Fascism. In 1966, Kennedy created the Media Workshop, an organization charged with fighting racism and discrimination in the media. The group led boycotts of advertisers who did not feature Blacks in their ads.

Kennedy’s lecturing career started in 1967 after she attended an anti-Vietnam War rally in Montreal. When Black Panther Bobby Seale was not allowed to speak, since his topic was going to focus on racism rather than on the war, Kennedy took the platform and started yelling and protesting. She gained attention and was soon invited to speak in Washington, D.C. Never afraid to speak her mind, she said about herself in Color Me Flo , “I’m just a loud-mouthed middle-aged colored lady with a fused spine and three feet of intestines missing and a lot of people think I’m crazy … I never stop to wonder why I’m not like other people. The mystery to me is why more people aren’t like me.”

Kennedy advocated for women’s liberation—for all women, not just Black women—and she urged the two races to work together. She helped found the Women’s Political Caucus and the National Black Feminist Organization. She was an original member of the National Organization for Women (NOW) and joined the group Radical Women to protest the 1968 Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Kennedy also founded the national Feminist Party, which in 1971 nominated Representative Shirley Chisholm (D-NY), the first Black woman elected to Congress, for president. Kennedy even protested the shortage of female bathrooms at Harvard University by leading a mass urination on the campus grounds.

On the abortion rights front, Kennedy organized feminist lawyers in 1969 to challenge the constitutionality of New York state’s antiabortion laws. She collaborated on briefs and cross-examined witnesses in pretrial hearings. The laws were overturned the following year. In 1971, Kennedy co-authored with Diane Schulder a book on the class action suit, Abortion Rap, one of the first books on abortion. Kennedy even took on the Roman Catholic Church by filing a tax evasion charge to the Internal Revenue Service, claiming that the church’s vocal and financial campaign against abortion breeched its tax-exempt status and violated the federal constitution’s call for the separation of church and state.

Kennedy continued her activism throughout her life and produced a weekly interview show on cable TV. Throughout her career she lectured at more than 200 colleges and universities. She spent much of her later years confined to a wheelchair.

Kennedy died in her Manhattan apartment on December 22, 2000, at the age of 84. As someone who was adamant about not wasting her life, Kennedy had said, “Sweetie, if you’re not living on the edge, then you’re taking up space.”

DIANE NASH (1938 – )

Born on May 15, 1938, in Chicago, Illinois, Diane Judith Nash grew up middle-class and was raised Catholic. Her father served in the military as a clerk during World War II, and her mother was a keypunch operator. After divorcing, Diane’s mother married John Baker, who worked as a waiter for the Pullman Company’s railroad dining cars.

Having attended both public and Catholic schools, Nash considered becoming a nun at one point in her youth. She also won several beauty contests as a teenager and became runner-up for Miss Illinois. In 1956, Nash graduated from Hyde Park High School in Chicago.

Nash changed her path when she attended Fisk University. She had first attended Howard University in Washington, D.C. but transferred to Fisk in Nashville, Tennessee in 1959. It was there that she came face-to-face with overt discrimination.

Witnessing segregation first hand led to her ambition to fight against segregation and prompted her to participate in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and nonviolent protests. She also worked tirelessly with the Selma Voting Rights Committee campaign, which helped Blacks in the South get to vote and gain political power.

In 1960, the spring after she enrolled at Fisk, she became a leader in the Nashville Student Central Committee, which organized sit-ins at discriminatory restaurants throughout the city. The success of the sit-ins on May 10 that year would make Nashville the first southern city in the country to desegregate lunch counters.

Matthew Walker, from left, Peggy Alexander, Diane Nash and Stanley Hemphill, eat lunch at the previously segregated counter of the Post House Restaurant in the Greyhound bus terminal in Nashville, Tenn. on May 16, 1960. This marked the first time since the start of the sit-in that Blacks were served at previously all-White counters in Nashville. Gerald Holly, The Tennessean

On February 6, 1961, she participated in a sit-in at a lunch counter in Rock Hill, South Carolina, with Ruby Doris Smith, Charles Jones and Charles Sherrod. They were all arrested, and the men were sentenced to hard labor. This followed a lunch counter sit-in that occurred a week prior by a group that came to be known as the “Friendship Nine.” Both groups implemented “Jail-No-Bail” tactics, in which they remained in jail as a way of showing their refusal to accept an unjust system. The Friendship Nine’s convictions were overturned in 2015, 54 years later.

Nash was on the front lines in the Freedom Rides to fight for the desegregation of public transportation in the South. When the Freedom Rides reached Anniston, Alabama, on May 14, 1961, the buses were burned and the activists beaten, forcing them to retreat to New Orleans. From there, it was up to Nash to carry the torch with a new group of Freedom Riders. In 1961, Nash coordinated the Nashville Student Movement Ride from Birmingham, Alabama, to Jackson, Mississippi. Participants in the Freedom Rides had given her sealed envelopes with their wills, in the event of their deaths.

“It was clear to me that if we allowed the Freedom Ride to stop at that point, just after so much violence had been inflicted, the message would have been sent that all you have to do to stop a nonviolent campaign is inflict massive violence,” said Nash in the 2010 documentary Freedom Riders.

Throughout the Ride, Nash recruited new Riders, alerted the press of their efforts, and forged relationships with the federal government and national Movement leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The Freedom Rides concluded in the fall of 1961 with yet another victory for the Civil Rights Movement; the Interstate Commerce Commission made segregated bus travel and terminals illegal, effective November 1st.

In 1961 Nash left college to become a full-time activist for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). She headed SCLC campaigns to register people to vote and desegregate schools. Although her work was applauded by fellow civil rights activists, she endured numerous arrests for the cause. In fact, she spent time in jail while she was pregnant with her first child; her crime was teaching nonviolent tactics to children.

Nash played a major role in the Selma Voting Rights Campaign that eventually led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. She was also appointed to a national committee by President John F. Kennedy that promoted passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Nash married fellow activist James Bevel in 1961. The couple had two children. In 1965 Dr. King awarded Nash and her husband SCLC’s Rosa Parks award for their contributions to civil rights. The couple divorced in 1968.

Nash was named a recipient of the Distinguished American Award from the John F. Kennedy Library and Foundation in 2003 and the LBJ Award of Leadership in Civil Rights from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum the following year. Additionally, she has been awarded honorary doctorates from Fisk University and the University of Notre Dame.

Historian David Halberstam considered Nash, “bright, focused, utterly fearless, with an unerring instinct for the correct tactical move at each increment of the crisis; as a leader, her instincts had been flawless, and she was the kind of person who pushed those around her to be at their best—that, or be gone from the movement.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Stay tuned to next week when I continue to share the stories of notable Black women in honor of Women’s History Month.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

I’m thrilled to share the news: my memoir, A Daughter’s Kaddish: My Year of Grief, Devotion, and Healing will be published this coming fall by Wonderwell Publishing. Watch for more information to come.