A Candle of the Lord

Only twenty days after my father died, I would attend my first Yizkor service. Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish year, would begin at sundown. I was unprepared/wasn’t ready.

This Day of Atonement is one of the four Jewish holidays on which the Yizkor (which literally means “May God Remember”) memorial service is recited. During the brief service, congregants ask God to remember and grant repose to the souls of the departed.

I thought about the Yizkors of my youth. My father believed, as many traditional Jews do, that you leave the sanctuary during the Yizkor service if both parents were living. Until my grandfather’s death, Dad always exited before Yizkor and returned when it ended. After my grandfather’s death, Dad would usher me out of the synagogue while he remained to recite the Yizkor prayers.

I didn’t want to be in the group that remained for Yizkor. I wanted to be in the “other” group – the group that got to wait outside the sanctuary. They had something I wanted – two living parents. Staying in the sanctuary for the service was another reminder of the public manifestation of my status as a mourner. It felt too soon. My permanent status as a mourner.

Even though I was already immersed in twice daily prayer in the presence of the 10-person minyan. ………….

“Why is it that people who haven’t lost a parent leave the synagogue during the Yizkor service?” I had asked my father in my youth.

“It would be ‘tempting fate’ to remain in the synagogue,” he said. Like many others, he believed that, if children stayed in shul when their parents were still alive, it could bring bad luck to the parents — it could tempt the “evil eye.”

Although Dad’s explanation was a common understanding, I chuckled. It was out of character for my always logical father to subscribe to an old superstition.

Since a common theme behind most Jewish rituals is sensitivity, I figured there had to be other explanations – like the fact that it could bring unnecessary pain to children to witness so many adults simultaneously shedding tears. Or the fact that those who left were demonstrating their respect to the mourners by allowing them to grieve in the presence of only those with the shared experience.

While it is not obligatory to recite Yizkor during the first year of mourning, I was determined to do everything to bring credit to my Dad’s memory and ensure the ascension of his soul.

On the eve of a Yizkor holiday, it is an ancient custom to kindle a Yahrzeit candle for the departed. The small candle sits in a glass jar only three inches high. The wax burns for 24 hours. As a very young girl, I had seen my mother light the candle for her mother and as I got older, I saw both parents light candles for each of their respective parents.

I began shivering as I realized I didn’t own a Yahrzeit candle. It was long minutes before the trembling ceased. I gripped the kitchen counter. Another symbol of the absoluteness of my father’s death. I was a mourner.

Yahrzeit candles were sold in synagogue gift shops and stores that specialized in Judaica. But their hours and locations were inconvenient for a working single mother who attended synagogue every morning and evening. I was told they were also sold in local grocery stores and their 24-hour availability made that the perfect choice. In our grocery store, in the aisle marked “Kosher,” I finally, after much searching, found the little glass jars on the bottom shelf.

It felt wrong to see them there – relegated to a lowly place – denigrating sacredness. Bottom shelves are the place where things like seven-pound cans of pork and beans and 20- pound bags of rice, are kept. And huge bags of sugar cereals with obscure names like Berry Krunch Heads and Cocoa Magic. Certainly an item of such religious significance should have a more respectable place. I made a mental note to share my upset with the store manager, but at another time, when I could talk less emotionally about the lack of sensitivity involved in putting Yahrzeit candles close to the floor.

I took the candle from the shelf, holding it reverently as I walked to the checkout line. The cashier put it into a small brown paper bag, which I carried home with the same care as a carton of eggs. As I took the glass jar from the bag, questions flooded my brain. Where do I light it? What prayer do I say? How do I make the moment sacred? And where do I keep a candle burning for 24 hours, while I’m away from home, in a way that would be safe?

I chided myself for the thought – clearly Jews all over the world, for hundreds of years, have left their Yahrzeit candles burning unattended and their houses hadn’t burned down as a result.

Unaware of the blessing to be said when lighting the Yahrzeit candle, I went to my collection of books on Jewish ritual practice, looking for the “right” blessing. Hours of research later, I learned that, because the lighting of the Yahrzeit candle is a time-honored tradition, rather than a commandment, there is no prescribed blessing.

“Jewish rituals are always preceded by a blessing!” I was talking aloud to no one. “How can this sacred act have no blessing?” I wondered, did the sages want us to reflect on our loved one, rather than be confined to a set blessing? Or was the idea for the mourner to remain focused on her own thoughts?

Lighting the Yahrzeit candle was part of the promise: I will remember you the rest of my life. The custom comes from the Book of Proverbs (chapter 20 verse 27): “The soul of man is a candle of the Lord.” The flickering flame of the candle reminds us of the departed soul of our loved one and the precious fragility of life — life that must be embraced and cherished at all times. Like a human soul, flames must breathe, change, grow, strive against the darkness and, ultimately, fade away. Like the flame of the candle, the soul also continuously strives to reach up to God. And it is believed that by lighting a Yahrzeit candle we help elevate the soul of our deceased loved one.

Before sunset on the evening of Yom Kippur I took the candle into my journaling room, the place in my house that felt most sacred to me. Light still streamed into the room from the sliding glass door along the far wall. I was alone with thoughts of my youthful father and his death at only age 76. I felt my heart pressing against my chest cavity, as if I would explode, as rage welled up inside me.

I shouldn’t be lighting this candle for you, Dad. You should still be alive. This feels so unfair.

The silence was broken by my angry screams. “Why, God . . .why did you have to take him? Why did you take such a good man and leave so many bad people walking the earth?”

Sinking to the floor, silent tears poured out, washing away the onrush of anger. With a trembling hand, I took a match from the box of kitchen matches – the only matches I could find in my house — and swooshed it across the striking surface on the outside of the box. It didn’t ignite. The second time it didn’t ignite. Finally, on the third attempt my hand steadied enough and I heard the sizzle of the match lighting. The flame danced on the end of the match as I picked up the little jar, struggling to hold the match still, until the flame met the wick. As I extinguished the match and smelled the sulfur, I mumbled some words that I no longer recall, pouring my heart out to the God who I believed was just but whose wisdom I felt justified to question.

Given my immersion in public prayer, performing this ritual at home – alone – was a stark contrast to the rest of my mourning practice. The cavernous feeling of the house matched the enormous emptiness of my heart.

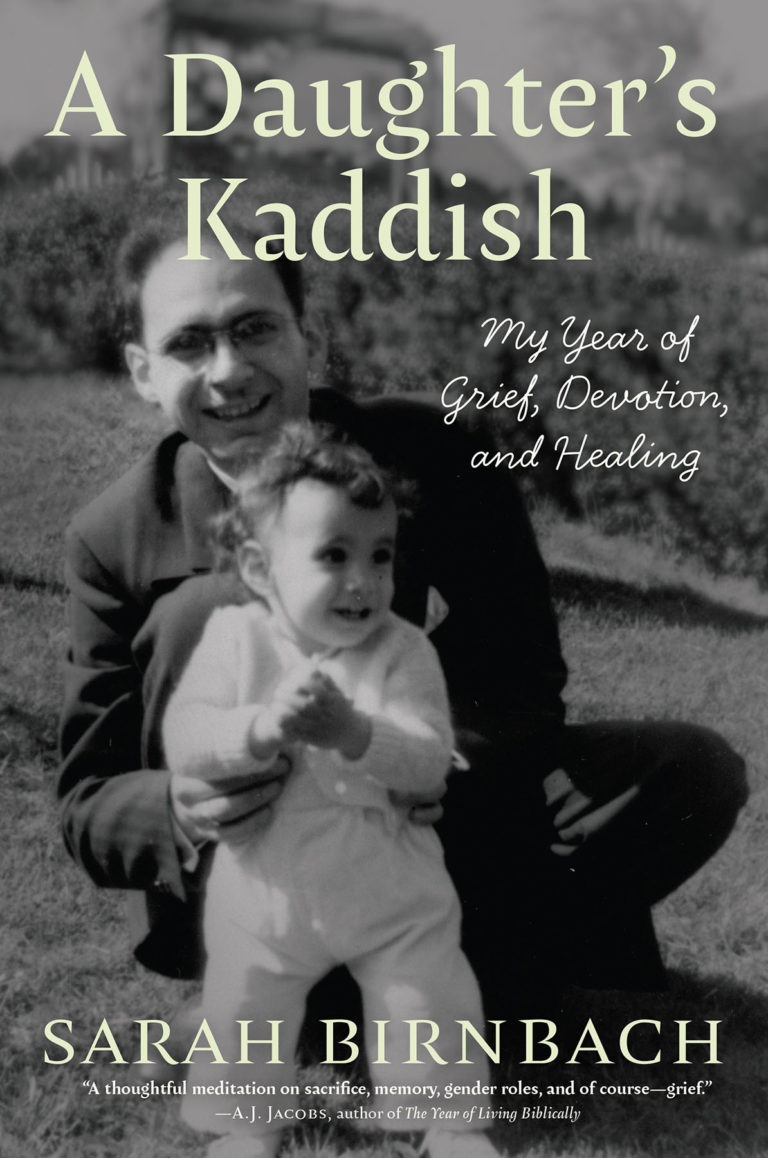

I placed the candle gently on my coffee table and sat to look at it. It seemed so tiny and alone there. I walked around the house, examining photos of my father. I chose the one in his favorite golf tee-shirt taken on his 75th birthday, and the last one ever taken of him, dressed in his tuxedo on the millennium New Year’s Eve cruise. I placed them next to the candle, as if to remind it for whom it was burning.

Sitting on my journaling sofa, watching the flickering blue and yellow flame, I remembered the night that we returned from the cemetery and I sat watching the flame of the shiva candle in my mother’s house. As I’d done that night, I sat with watering eyes fixed on the flame, mesmerized, committed to the redemption of my father’s soul and feeling the oppressive weight of my loss.

Slowly I began composing myself, reminding myself that this emptiness I felt would not help me get through the following 25 hours of fasting and atonement. I needed strength and energy to remain in synagogue the following day without food or water. Dad would not be there to usher me out before Yizkor. Now I had to stay. Nor would he be there at the day’s end to discuss the ease or difficulty of that year’s fast, a conversation that always had us consoling and cajoling each other.

I miss you, Daddy.

I dragged myself to the bathroom sink, splashed cold water on my puffy eyes and red face, and left to join my friends for the pre-fast dinner and the warm embrace of their friendship. As I sat in the synagogue, watching the sun set, I thought of the light of the Yahrzeit candle illuminating the dark of my home and of the many happy memories of my father – laughing and splashing in the waves at the beach every summer of my youth, sitting and watching Ed Sullivan in the living room on Sunday nights, working together in his office, participating in Father/Daughter night in my high school, dancing together at my sorority formal, reading the Value Line investment reports together and discussing mutual funds – that would always remain to light up my life.