Combating Racism – Structural Racism and Health Inequalities

COVID-19 has shined a light on health disparities that have been in existence in our country for centuries. The startling and disproportionate death rate among Black Americans around the country from COVID-19 is a horrific reminder of the persistent inequities and the need for solutions to address them.

THE ISSUES

A recent Washington Post special report, based on an analysis of records from 5.8 million people who tested positive for the coronavirus from early March through mid-October, found that people of color continue to die from the coronavirus at much higher rates than Whites. A recent study showed that despite the fact that Blacks represent 13.4% of the population, those counties with high Black populations account for almost 60% of coronavirus cases. On a national level, Black Americans account for 52% of COVID diagnoses and 58% of the national death toll. In Wisconsin alone, where Blacks are just 6% of the state’s population, they account for 27% of the deaths from the novel coronavirus.

The health gap between minority and non-minority Americans has persisted, and in some cases, has increased in recent years. Black men, for example, experienced an average life expectancy of 61 years in 1960, compared with 67 years for their White male peers; in 2003, White males enjoyed an average life expectancy of 75.3 years, relative to 69.0 years for Black males. In addition, Black children have a 500% higher death rate from asthma compared with White children.

Health disparities have been well documented in medical literature. In 2002, the Institute of Medicine published Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, a study that concluded that: “. . . racial and ethnic minorities experience a lower quality of health services and are less likely to receive even routine medical procedures than are White Americans.”

Black Americans have the highest rates of morbidity and mortality of any U.S. racial and ethnic group. The mortality rate for Blacks is approximately 1.6 times higher than that for Whites – a ratio that is identical to the Black/White mortality ratio in 1950. The Black infant mortality rate (babies who die before their first birthday) is more than two times higher than for whites – 11.4 deaths per thousand live births for Blacks compared with 4.9 for Whites.

Despite steady improvement in the overall health of the U.S. population, Blacks experience the highest rates of mortality from heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, and HIV/AIDS than any other U.S. racial or ethnic group.

BIOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES

The study of racial variations in health has been driven by a genetic model that assumes that the genes that determine race are linked with the genes that determine health, and that the health of a population is determined predominantly by biological factors. Recent studies published in the Journal of Health Politics, Policy & Law have shown that there is more genetic variation within races than between races and that race is more of a social construct than a biological construct.

Attributing racial disparities in health to inherited biological differences in susceptibility to disease is rooted in a long-standing U.S. tradition that continues to present day. The future of the institution of slavery rested on the belief that Blacks are innately inferior to Whites—for instant belief in racial differences in cranial sizes or oxygen-carrying capacity—and while these beliefs have long been discredited, the tradition of ascribing racial disparities in health to fixed biological traits persists.

To disprove the biology theory, surveys of Black populations in West Africa and African-origin populations in the Caribbean reveal that the rates of hypertension and diabetes, long believed attributed to race, are 2-5 times lower than those of Black Americans or Black Britons.

A New England Journal of Medicine editorial stated: “Slavery has produced a legacy of racism, injustice, and brutality that . . . infects medicine as it does all social institutions.”

FACTORS IN RACIAL DISPARITIES IN HEALTH

Experts have argued that the clustering of COVID-19 cases and the high morbidity and mortality rates among Black Americans are more of a social and economic phenomenon. This is due to a number of factors.

SOCIETAL FACTORS

The largest study of its kind, conducted by Daniel Spratt, M.D., found that societal factors such as a lack of health insurance, less access to high-quality care, and lower overall socioeconomic status, rather than genetics, contribute to higher rates of disease among minorities.

Many Blacks are afraid to seek care even if they are very sick. And as layoffs have accelerated since March 2020, economic factors have led more families to live in multigenerational homes, leaving families and friends crammed into small spaces with no place for a “sick room” to isolate patients.

In addition, minorities disproportionately represent front-line jobs and/or serve as essential workers with daily interaction with the public and an increased risk of exposure.

DISTRUST OF MEDICINE

As hope for an end to the pandemic lies in a vaccine that has had promising results in studies, polling shows that many minority populations are distrustful of the vaccine and express reservations about being vaccinated.

A recent Washington Post article, Coronavirus Vaccines Face Trust Gap in Black and Latino Communities, highlights results of a study that show vaccine hesitancy in communities of color. Perhaps its most sobering findings: only 14 percent of Black people trust that a vaccine will be safe, and only 18 percent trust that it will be effective in shielding them from the coronavirus.

The New York Times columnist Charles Blow places these vaccine concerns within a historical context. He states, “[t]he unfortunate American fact is that Black people in this country have been well-trained, over centuries, to distrust both the government and the medical establishment on the issue of health care.”

The lasting damage to Black communities’ trust in government has resulted from the horrendous exploitation that Black men and women have endured in the United States in the name of medical research. Most prominent is the unethical Tuskegee Study.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study was conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in conjunction with the Tuskegee Institute, a historically black college in Alabama. Investigators enrolled 600 impoverished Black sharecroppers from Macon County, Alabama – 399 of whom had latent syphilis and a control group of 201 men who were not infected. The men were deceived on multiple levels: they were promised medical care from the federal government which they never received; they were initially told that the study was to last six months, it lasted 40 years; the men were never told that they would not be treated. Despite the availability of penicillin by 1947, the standard treatment for syphilis, the men were never treated with the antibiotic. The study caused the deaths of 128 of its participants, either directly from syphilis or from related complications.

Also prominent is the case of Henrietta Lacks, in which doctors at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland took samples of her cells while diagnosing and treating her aggressive cervical cancer. Lacks was a Black woman and in 1951, Johns Hopkins was one of only a few hospitals that provided medical care to Black people. But because her cells turned out to have an extraordinary capacity to survive and reproduce, they were shared with other scientists and have been used in key discoveries in many fields, including cancer, immunology and infectious disease. The problem: the cells were taken without her knowledge or consent and neither she nor her family received remuneration. None of the biotechnology or other companies that profited from her cells passed any money back to her family. For decades after her 1951 death at age 31, doctors and scientists repeatedly failed to ask her family for consent as they gave her medical records to the media and published her cells’ genome online.

GEOGRAPHICAL FACTORS

Geographical proximity to health facilities can affect a patient’s access to adequate health services. Black Americans face a relative scarcity of health care providers and health care facilities in minority communities. In some instances there are few options for patients who are unable to drive, to be driven to, or to take public transportation to a health facility. Insufficient transportation is a significant access-related barrier to equitable care.

In addition, many Blacks live in more densely packed neighborhoods and multigenerational households. These neighborhoods are often characterized by poor housing conditions, exposure to physical and chemical toxins, less access to quality schools that can lead to better education and higher paying jobs, less open spaces, and less access to fresh fruits and vegetables. According to David Williams, Professor of Public Health at Harvard University, “One’s zip code is a better predictor of quality health care than one’s genetic code.”

ACCESS TO QUALITY CARE

In addition, minorities face a long history of unequal access to medical care, which has impacted treatment decisions and outcomes. A study using data from the Society for Critical Care Medicine found that Black patients were more likely than Whites to receive an older, less-expensive and riskier blood thinner linked to higher mortality from COVID-19. Blood thinners have become a critical weapon in the arsenal used by doctors against the disease because many patients with severe disease develop clots.

It is not clear whether the administration of that medicine is related to insurance coverage, physician preference, or something else. One of the study’s authors, Venky Soundararajan, chief science officer of data firm Nference, wondered whether some doctors chose the older, more established product for minority patients because the newer drugs were overwhelmingly tested on Whites.

A 2018 study of 400 hospitals in the U.S. found that Black patients with heart disease received older, cheaper and more conservative treatment than their White counterparts.

A Boston-based data firm said Blacks with symptoms such as coughing may be less likely to get access to scarce coronavirus tests. An analysis of testing in New York City found that more testing existed in White neighborhoods although the highest positivity rates were in communities with a higher share of Black and Hispanic residents.

Furthermore, many inner city health care facilities suffer from overcrowding, inadequate infrastructure, and inefficient organizational structures.

COSTS

Although the Affordable Care Act has narrowed racial and ethnic gaps in access to health insurance and care, Black Americans are still less likely than Whites to have health coverage, and more likely to avoid care because of cost. A lack of insurance means lower access to care, poorer health outcomes, and a lower probability of consistent care.

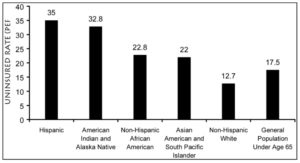

The chart below shows the probability of being uninsured by populations under age 65.

Source: Hoffman and Pohl, 2000

In addition, so many minorities are struggling to make enough money for basic needs like food and shelter that the coronavirus has sometimes seemed a secondary concern. Even the most vulnerable — men and women over the age of 60 with known health issues — have to go to work to make ends meet. And in addition to everyday expenses, some families are now being hit with huge bills for funerals.

FOOD INSECURITY

Results from the National Poll on Healthy Aging showed food insecurity disparities by age, race, ethnicity and education worsened due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Access to nutritious food and health status are closely linked.

Many low-income and minority neighborhoods in the U.S. lack accessible supermarkets or supermarkets served by adequate public transportation. Residents of these neighborhoods must rely on small grocery stores or convenience stores which carry few, if any, fresh fruits and vegetables. Areas where people have poor access to fresh and healthy foods are sometimes called “food deserts.” Thus, unhealthy eating is often the result of structural inadequacies in accessing healthy foods and not necessarily to personal dietary choices.

The connection between healthy diets and good health outcomes is well established. The existence of “food deserts” contributes to the continuation of racial and ethnic health disparities. Eliminating “food deserts” in underserved communities can help eliminate chronic diseases, such as diabetes, and help achieve greater equity in health outcomes among racial minorities.

As we try to prevent the spread of coronavirus, we need to ensure that all individuals can get food that aligns with their health conditions so as not to exacerbate diabetes, hypertension, digestive disorders and other conditions that increase vulnerability to the virus.

LACK OF MINORITY DOCTORS

Ryan Huetro, M.D., a physician at Michigan Medicine, found that increasing the probability that minorities see doctors of their own race can improve health care delivery.

Black patients may feel warier with a White doctor than a Black doctor and White doctors may feel less comfortable caring for minority patients. Dr. Huetro found evidence suggesting that when physicians and patients share the same race or ethnicity, this improves time spent together, medication adherence, shared decision-making, wait times for treatment, patient understanding of risks, and patient perceptions of treatment decisions. Not surprisingly, implicit bias from the physician is decreased.

A 2019 study by the Association of American Medical Colleges entitled “Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019” found that among active physicians, 56.2% identified as White, 17.1% identified as Asian, 5.8% identified as Hispanic, and 5.0% identified as Black or Black. (13.7% identified race as “unknown.”)

CONFUSION

Misunderstandings affect the delivery of adequate care through poor exchange of information, loss of important cultural information, confusion about physician instructions, poor shared decision-making, and ethical compromises, such as difficulty obtaining informed consent. In addition, low English reading proficiency may disproportionately and negatively affect many racial and ethnic minority patients’ ability to read and understand written material from health plans and health care providers. There is significant evidence that language affects variables such as follow-up compliance and satisfaction with services. Linguistic difficulties may present a barrier to the use of health care services, decrease adherence with medication regimes and appointment attendance, and decrease satisfaction with services.

RACISM BY MEDICAL PROVIDERS

Racial bias is pervasive in health care, particularly in the assessment and treatment of pain. In a national study that included almost a million emergency room visits, Black children in severe pain from acute appendicitis had just 1/5 the odds of receiving opioid painkillers compared to White children, even after adjusting for other factors.

According to a 2016 study, broader racist myths about Blacks still exist. During slavery times, violence against enslaved Black people was justified by false beliefs that Blacks had greater tolerance for pain, and thicker skin. This study found that one third of 222 White medical students and resident held that false belief. These respondents are less likely to perceive the intensity of Black patients’ pain and recommend appropriate treatment.

RECOMMENDATIONS & POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

Research suggests that a variety of interventions may be effective as a part of a comprehensive, multi-level strategy to address racial and ethnic disparities in health care.

1. Eliminate or modify payment practices that fragment the health care system.

Variations among health plans, and the disproportionate presence of disadvantaged minority groups in lower-end health plans is a major source of disparities in health care provision. Even within a broad federal program such as Medicare, tiers of health systems exist (e.g., more than 60% of Medicare beneficiaries possess supplemental coverage), with minorities typically congregated at lower levels. The result: differences in the intensity of care between lower and higher-end health plans.

Studies consistently demonstrate the association between insurance status and use of health care resources. For example, patients seen in emergency departments are more likely to be admitted to the hospital and have a longer length of stay if they are privately insured, rather than publicly insured or uninsured and Medicare patients without supplemental coverage are less likely to have the influenza vaccination, cholesterol testing, mammography, or Pap smears than those with supplemental coverage.

Efforts to reduce the socioeconomic segmentation of the medical marketplace would help to diminish racial and ethnic disparities in health care provision.

2. Strengthen Doctor-Patient Relationships.

The consistency and stability of the doctor-patient relationship is an important determinant of access to care. Having a consistent relationship with a primary care provider can help to reduce minority patient mistrust of health care systems and providers, particularly if the provider is able to bridge cultural and linguistic gaps. Minority patients can benefit from stronger bonds with those physicians who understand the barriers to care they face in trying to navigate through health systems.

Several strategies can help to promote the stability of patient and provider relationships in publicly funded health plans. Federal and state performance standards for Medicaid-managed care plans, for example, could include guidelines that encourage reasonable patient loads per primary physician and time allotments for patient visits. Regulations governing health plans’ participation in Medicare should include similar guidelines.

Health systems should ensure that every patient, whether insured privately or publicly, through Medicare or Medicaid, has a sustained relationship with an attending physician able to help patients effectively navigate the health care bureaucracy effectively (e.g., to help patients obtain referrals and secure appropriate specialty care and other health care resources).

Policies that strengthen provider-patient relationships in publicly funded health plans and that promote the consistency of these relationships should be adopted.

3. Increase the proportion of racial and ethnic minorities among health professionals.

Greater racial and ethnic diversity in the health professions is necessary to strengthen patient and provider relationships. Racial concordance of patient and provider generates greater patient participation in care processes, higher patient satisfaction, and greater adherence to treatment. In addition, racial and ethnic minority providers are more likely than their non-minority colleagues to serve in minority and medically underserved communities. To the extent legally permissible, affirmative action and other efforts are needed to increase the proportion of racial and ethnic minorities among health professionals.

The Health Enterprise Zones Act is one step in this direction. Geographic areas with measurable and documented economic disadvantage and poor health outcomes can be designated as a Health Enterprise Zone (HEZ). The goals of the act are to:

- Reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations in designated geographic areas,

- Improve health care access and health outcomes in underserved communities, and

- Reduce health care costs and hospital admissions and re-admissions.

A 2020 bill introduced in Congress proposes to incentivize health care providers to work in disadvantaged communities by providing: a) a work opportunity credit for hiring HEZ workers, b) a tax credit for qualitied HEZ workers, c) grant programs to reduce health disparities and improve health outcomes in HEZs, and d) a student loan repayment program for eligible providers practicing in HEZs.

4. Apply the same managed care protections to publicly funded HMO enrollees that apply to private HMO enrollees.

Some evidence indicates that low-income and ethnic minority patients enrolled in managed care plans are less likely to have a regular provider than similar patients in fee-for-service plans, are more likely than Whites to be denied claims for emergency department visits, and are less satisfied with many aspects of the care they receive in managed care settings. Other studies find that the intensity of care is lower for some populations within managed care settings relative to other care systems.

5. Provide greater resources to the U.S. DHHS Office of Civil Rights to enforce civil rights laws.

The U.S. DHHS Office of Civil Rights (OCR) is charged with enforcing those federal statutes and regulations that prohibit discrimination in health care (principally Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act). The agency, however, has suffered from insufficient resources to investigate complaints of possible violations, and has long abandoned proactive, investigative strategies. Complaints to the agency have increased in recent years, while funding has decreased. This decrease in funding has negatively affected OCR’s ability to conduct on-site complaint investigations, compliance reviews, and local community outreach and education.

Congress and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should provide adequate funding to the U.S. DHHS Office of Civil Rights to expand the agency’s capabilities to address civil rights complaints and carry out its oversight responsibilities. In addition, OCR should resume the practice of periodic, proactive investigations, both to collect data on the extent of civil rights violations and to provide a deterrent to would-be lawbreakers.

6. Enhance patient-provider communication and trust by providing financial incentives for practices that reduce barriers and encourage evidence-based practice.

Well-crafted provider incentives can have a positive role in reducing disparities in care. Greater economic rewards for time spent engaging patients and their families can help to overcome barriers of culture, communication, and empathy. Economic incentives should be considered for practices that enhance provider-patient communication and trust, and that reward appropriate screening, preventive, and evidence-based clinical care.

Further, payments linked to favorable clinical outcomes, where reasonably measurable (e.g. control of diabetes, asthma, and high blood pressure), would foster these outcomes. Movement toward incentive opportunities along these lines could be started by private accrediting bodies, encouraged by business and professional leaders, and even initiated by public payers. Health care organizations, clinicians, purchasers, and other stakeholders should align the incentives with the goal of quality improvement.

7. Support the use of community health workers.

Community health workers offer promise as a community-based resource to increase racial and ethnic minorities’ access to health care. Community health workers have been participants in health care systems since the 1960s. These individuals, often termed lay health advisors, indigenous health workers, or health aides fulfill multiple functions in helping to improve health outcomes. They have been defined as being “community members who work almost exclusively in community settings and who serve as connectors between health care consumers and providers to promote health among groups that have traditionally lacked access to adequate care.” One of the greatest assets of lay health programs is that they build on the strengths of community ties to help improve outcomes for its citizens.

Lay health workers can:

- help improve the quality of care and reduce costs,

- facilitate community participation in the health system,

- serve as liaisons between patients and health care providers,

- educate providers about community needs and the culture of the community,

- provide patient education,

- promote consumer advocacy and protection,

- contribute to continuity and coordination of care,

- assist in appointment attendance and adherence to medication regimens, and

- help to increase the use of preventive and primary care services.

During its inception, lay health workers collaborated with public health departments, homeless programs, and community health centers. More recently, partnerships have been formed with academic medical centers. For community health worker programs to be successful, they must be designed properly and workers must be adequately trained and supervised.

Programs to support the use of community health workers especially among medically underserved and racial and ethnic minority populations, should be expanded, evaluated, and replicated.

8. Implement multidisciplinary treatment and preventive care teams.

Multidisciplinary team approaches – utilizing physicians, nurses, dietitians, and others – have been effective in reducing risks for patients with coronary heart disease, hypertension, and other diseases. Multidisciplinary teams coordinate and streamline care, enhance patient adherence through follow-up techniques, and address the multiple behavioral and social risks that patients face, particularly racial and ethnic minority patients. They may save costs and improve the efficiency of care by reducing the need for face-to-face physician visits and improve patients’ day-to-day care between visits. Multidisciplinary team approaches should be more widely implemented as a means to improve care delivery, implement secondary prevention strategies, and reduce risks.

9. Implement patient education programs to increase patients’ knowledge of how to best access care and participate in treatment decisions.

Culturally appropriate patient education programs can improve patient participation in clinical decision-making and care-seeking skills, knowledge, and self-advocacy. Information that flows in both directions is important for increasing patient cooperation, engagement, and adherence to medical regimes.

For example, the Bayer Institute has developed a program called PREPARE, a six-step program using a self-administered audiotape and guidebook to help patients prepare for office visits. Complementary materials were also developed for use by providers of health care to support and encourage use of the program. In addition, some medical institutions, such as the Ohio State University Medical Center and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Center, have established internet-based programs to help answer patient questions about topics such as pain management, medications, medical procedures, nutrition, and health promotion.

Similarly, an individual education and coaching program in pain self-management for cancer patients was demonstrated to improve ratings of pain severity over patients who did not receive the intervention.

Culturally appropriate patient education programs tailored to specific racial and ethnic minority populations should be developed, implemented, and evaluated.

10. Increase telemedicine as a means to increase access to medical care.

Studies have shown that many Black Americans express concerns about confidentiality, privacy, and the physical absence of the provider. These concerns may reflect the lower levels of trust in health care innovations that result from the legacy of past abuses in the U.S. medical system, as well as ongoing racism in health care.

In addition, the Institute of Medicine has identified illiteracy, distrust of technology, fear that ones’ identity could be stolen, and the perception of the Internet as “insecure,” as potential barriers to the delivery of telemedicine in underserved areas. The concerns expressed by Black Americans to the use of telemedicine reflect a vulnerability to placing trust in a medical system that has historically been untrustworthy.

It will be necessary to tailor approaches to the introduction, marketing, and implementation of telemedicine among Black populations. It is important to identify the gaps in knowledge, the misinformation that can lead to distrust of new technology, or the false expectations about it use. To lower barriers to acceptance of telemedicine it will be important to develop educational materials that address these concerns. Physicians, physicians’ assistants, and nurses involved in telemedicine need to be well informed about the concerns of Blacks so they can address these concerns, even if the patients do not voice them.

CONCLUSION

Although systemic racism cannot be quickly rooted out, even small measures that can be quickly implemented have been proven to make a difference and save lives. Successful changes in Michigan offer an example for other states to follow.

Faced with extreme disparities in COVID-19 deaths, Michigan officials undertook a series of steps, from boosting testing to connecting people of color with primary care doctors. Garlin Gilchrist II, Michigan’s lieutenant governor, formed one of the nation’s first state racial disparities task forces on COVID-19 back in April. Made up of 23 community organizers, doctors and other experts, the group focused not only on boosting testing and contact tracing, but also tailoring messages on mask-wearing and other public health precautions to Black communities. It also addressed broader systemic issues, such as access to primary care, and helping those in rural areas access telemedicine.

When state epidemiologists ran the numbers again in September, they found a huge change: Black residents who in April accounted for 29.4 percent of cases and 40.7 percent of deaths now made up only 8 percent of cases and 10 percent of deaths — very similar to their percentage in the population. Gilchrist emphasized the state’s efforts have not been complicated. “I think the reason we have been able to make progress is we chose to focus on it,” he said.

The state’s rapid progress proves the issues are neither intractable, nor rooted somehow in biology.

In addition to the ethical and moral reasons to eliminate health disparities, there are economic reasons to do so as well. A 2011 study estimates that the economic costs of health disparities due to race for Black Americans, Asian Americans and Latinos from 2003-2006 was a little over $229 billion. In a report issued in September, 2009, the Urban Institute calculated that the Medicare program would save $15.6 billion per year if health disparities were eliminated. The study concluded that if the prevalence of diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and stroke in the Black communities were reduced to the same prevalence as those diseases in the White population, $23.9 billion in health care costs would be saved in 2009 alone.

In order to address the deadly virus and address related health disparities, policy experts must collect data, particularly breaking down data by race and ethnicity, must respond to these disparities, and must understand the magnitude of medical mistrust that exists in communities of color, and the historical context for the concerns.

The U.S. infrastructure for measuring disparities remains inadequate at both the federal and state levels. State-based data, such as vital records, and Medicaid administrative data often do not collect information on race in standardized ways. Strengthening the U.S. data infrastructure will enable policymakers to monitor the effects of their policies on health disparities.

Health care is therefore necessary but insufficient in and of itself to redress racial and ethnic disparities in health status. A broad and intensive strategy to address socioeconomic inequality, concentrated poverty in many racial and ethnic minority communities, inequitable and segregated housing and educational facilities, individual behavioral risk factors, as well as disparate access to and use of health care services is needed to seriously address racial and ethnic disparities in health status.

Health professionals and policymakers must recognize the importance of health care as a resource that is tied to social justice, opportunity, and the quality of life for individuals and groups. The productivity of the workforce is closely linked with its health status, yet if some segments of the population, such as racial and ethnic minorities, receive a lower quality and intensity of health care, then these groups are further hindered in their efforts to advance economically and professionally. It is therefore important from an egalitarian perspective to expect equal performance in health care, especially for those disproportionately burdened with poor health.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

A primary resource for this newsletter is:

Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Institute of Medicine, Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Washington (DC), 2003.