Combating Racism – Domestic Slave Trade

“History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived,

But if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

Maya Angelou

NOTE: As “Negroes” was the term used to refer to African Americans and Black Americans during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, I have included this word in this newsletter, intending no disrespect or offense.

Last month my husband and I visited Charleston, South Carolina, a city we’d never been to together. One of our stops was the Old Slave Mart Museum, where I learned a lot about Charleston’s role in our nation’s slave trade.

I learned that there were two kinds of slave trade in America—the transatlantic slave trade, during which European and American slave traders captured or bought more than 12 million African men, women, and children to these shores to work as slaves.

Charleston was a port of entry for many enslaved African Americans who survived the transatlantic passage. But it also became a primary site for the domestic slave trade.

The Old Slave Mart Museum is the site of Charleston’s Old Slave Market. Before visiting the museum, I assumed that the men, women and children who were bought and sold here were brought from Africa. But I learned otherwise. The domestic slave trade involved enslaved men, women and children born in America—the children and grandchildren of captured Africans. They came from states like Virginia and my home state of Maryland. This domestic slave trade, which lasted into the Civil War, was the focus of the Old Save Mart Museum.

Importing enslaved Africans was outlawed by an act of Congress in 1807 and became effective on January 1, 1808. The law was rooted in an obscure passage in Article I, Section 9 in the U.S. Constitution which stipulated that importing enslaved people could be prohibited 25 years after the ratification of the Constitution.

Article I, Section 9. The migration or importation of such persons as any of the states now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a tax or duty may be imposed on such importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each person.

Without passage of the Act to Prohibit the Importation of Slaves (1807), it’s possible that the shipping of enslaved people might have accelerated, given the growth of the cotton industry following the invention of the cotton gin. To read the full text of the law, click here.

In the early 1800’s, as the transatlantic slave trade was ending, cotton production was on the rise, and America was moving west, creating a new demand for slave labor. The sale and brokering of domestic enslaved Americans emerged to feed this growing demand for workers.

The Museum in which I stood had been Ryan’s Mart, a showroom built solely for the purpose of buying and selling enslaved men, women, and children. During the market’s operation, crowds of slave traders and buyers auctioned humans for bondage. While slaves were waiting for the auction block, they were put in a jail behind the building. (That jail no longer stands.) A doctor would examine them, they would be dressed, fed to fatten them up, and made to dance and exercise so their muscles appeared more toned. Their skin would be greased to give it a healthy shine. Girls’ hair would be oiled and men’s beards would be dyed black to hide any evidence of gray.

After we returned from our trip, I determined to learn more about this domestic slave trade and stumbled across a YouTube video by Margaret Seidler, who calls herself “The Accidental Historian.” She has done considerable research into the domestic slave trading that took place in Charleston between 1800-1832. You can watch her 45-minute video here.

I learned about William Payne and his company, William Payne & Sons. William Payne emigrated from Ireland to South Carolina in the mid-1780’s, ostensibly to seek his fortune. He was appointed clerk to Edward Butler, nephew of Founding Father Pierce Butler, who is best remembered for introducing the Fugitive Slave Clause at the Constitutional Convention. By 1790, Payne had a falling out with Butler who referred to the Irish man as “well versed in hypocrisy and falsehood” and labeled him a “scoundrel.”

Payne’s first business venture was a “cash store” retail business but after going bankrupt in 1803, he found more lucrative employment auctioning slaves. Payne’s first recorded advertisement to sell enslaved people appeared on March 21, 1796. This sale was on behalf of the estate of John Witherspoon, which included “three Negroes.”

Margaret Seidler found over 1100 newspaper ads confirming that the Payne family prospered from the sale of at least 9,217 enslaved people between 1800 and his death in 1834. After that, his son, Josiah S. Payne continued selling enslaved persons.

She has put together 28 pages of Excel spreadsheets showing the sales, including the number of people being sold. Below is a sample of one of her spreadsheets. The highlighted line represents the 1819 sale of 360 enslaved people from the Estate of John Ball.

Below is a snippet of the advertisement for the sale of the 360 Negroes that is highlighted in Seidler’s spreadsheet above.

Payne’s commission was 1% of that sale, or $3,083.19. That is the equivalent of $63,011.31 in 2020 dollars.

To learn more about this particular sale, two significant sources include: “Sale and Separation, Four Crises for Enslaved Women on the Ball Plantation” by Cheryll Ann Cody, in Working Toward Freedom: Slave Society and Domestic Economy in the American South, edited by Larry E. Hudson, pp. 119-42. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 1994 and Slaves in the Family by Edward Ball, Ballantine Books, 1998.

The chart below shows the number of people sold by Payne & Sons by year. According to Seidler, these are conservative numbers as not all sales can be accounted for.

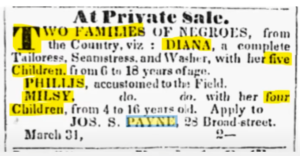

I had erroneously believed that many auctioned families were torn apart. But I have since learned that families were often sold intact, based on the belief that keeping families together would reduce the chances of any member running away. Here are two such ads—the first from May 1810 and another from March 1834.

In crafting his ads, Payne made the enslaved people sound highly skilled. The more valuable he made them out to be, the more money he could get for them, and the higher his commission. In ads he referred to one man as “a first rate painter;” an enslaved woman was advertised as “a first rate cook,” another was advertised as “a first rate nurse,” and yet another was “a prime young Wench, an excellent seamstress and house servant.”

Most of Payne’s auctions consisted of estate sales, or sales to pay mortgage debts or tax liens. Payne worked as an agent for the Charleston sheriff to recoup unpaid tax liens. The ad below shows Payne’s collaboration with the Charleston city sheriff in selling enslaved “Negro Fellows” to collect taxes.

Ironically, in 1810, Payne co-founded the Charleston Bible Society. It is hard for me to imagine that a man can spread the word of God while simultaneously brokering the sale of humans.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Maya Angelou’s quote, which appears in the Old Slave Mart Museum, reminds us that our history of slavery cannot be unlived. But with courage, we can work together to combat the racism that continues to exist today. I invite you to join me in this quest.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

I’m excited to share the news: my memoir, A Daughter’s Kaddish: My Year of Grief, Devotion, and Healing will be published this fall by Wonderwell Publishing. Watch for more information to come.