Combating Racism – Critical Race Theory

Image by Katty Huertas for The Washington Post

Newspapers, news shows, and the internet have been inundated with comments about critical race theory (CRT for short) in recent months. Detractors have claimed that the academic movement is “planting hatred of America in the minds of the next generation” and that it teaches children “to be ashamed of their skin color.” I wanted to understand CRT from an unbiased, un-politicized perspective. Here is a summary of what I have learned.

PURPOSE

Critical race theory is an academic framework formed by legal scholars more than 40 years ago to look at laws and regulations with an eye to whether they are promoting systemic discrimination in society. The core idea is that race is a social construct and that racism is not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something systemic—embedded in legal systems and policies.

The purpose of critical race theory is to provide Americans with a way to understand the legacy of racism even though those stories sometimes hurt. It looks at the way that racial unfairness has been woven into the fabric of our institutions.

The direct academic origins were the work of former Harvard law professor Derrick Bell, along with legal scholars Kimberle Crenshaw and Richard Delgado, among others, who rigorously challenged mainstream narratives of steady racial progress. Their analysis was first started to determine how to address injustice in the way the legal system has historically treated people of color. They sought to understand the puzzling persistence of racism in our legal, political, and economic systems in light of civil rights legislation; they attempted to show how the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 failed to deliver liberty and justice for Black Americans. Critical race theorists sought to explain how our laws and institutions continue to circumscribe the rights of racial minorities (e.g., in segregation, criminal justice, school funding, redlining, discriminatory lending to name a few).

Critical race theory emphasizes outcomes, rather than personal experience and an individual’s own beliefs, and calls for these unequal outcomes to be rectified.

THE DEBATE

Over the past year, the idea of critical race theory has become a political flashpoint. The racial reckoning spurred by the killing of George Floyd brought racial injustices back into the spotlight and some schools began to implement reforms to better address racism in the classroom.

The term “critical race theory” has now been cited as the basis of all diversity and inclusion efforts regardless of how much it’s actually informed those programs.

The previous administration pushed for “patriotic education” and accused teachers who discussed racism and bias with students of “left wing indoctrination.” Some claim that the theory is racist because White people will face discrimination in order to achieve more equitable outcomes. One Southern Senator called CRT “a lie and it is every bit as racist as Klansmen in white sheets,” and claimed that it teaches students that “all White people are racist.”

The Heritage Foundation recently claimed that, “When followed to its logical conclusion, CRT is destructive and rejects the fundamental ideas on which our constitutional republic is based.” The organization blamed CRT for the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, LGBTQ clubs in schools, diversity training in federal agencies and organizations, California’s recent ethnic studies model curriculum, the free-speech debate on college campuses, and alternatives to exclusionary discipline—such as the Promise program in Broward County, Fla., that the Obama administration considered a model for other school districts to follow and which some parents blame for the Parkland school shootings.

HISTORICAL BACKDROP

On March 21, 1925, Tennessee enacted a law prohibiting teachers in any state-supported school (including universities) from teaching “any theory that denies the Story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible,” including that man has descended from a lower order of animals. This was the first law that put teachers at risk of prosecution for teaching evolution.

On May 5, 1925, John T. Scopes, a high school teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, was charged with teaching evolution from a chapter in George William Hunter’s textbook, Civic Biology: Presented in Problems (1914), which described the theory of evolution, race, and eugenics (the study of how to arrange reproduction within a human population to increase the occurrence of desirable characteristics).

The Scopes trial, The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes, commonly referred to as the Scopes Monkey Trial, was held in July 1925. Scopes was accused of violating Tennessee’s Butler Act, named after John Washington Butler, head of the World Christian Fundamentals Association, which had made it unlawful to teach human evolution in any state-funded school. The trial drew intense national publicity and brought about an epic battle between science, modernity, and progress on one side, and religion, traditionalism, and conservatism on the other. The case was seen both as a theological contest and as a trial on whether modern science should be taught in schools. On July 20, 1925, Scopes was found guilty of violating the Tennessee law, which stayed in effect for decades after Scopes’ guilty verdict.

Of all the famous American court cases, it is hard to find one better suited than the Scopes trial to serve as a metaphor for the current culture wars. Scopes may have been nothing more than a misdemeanor trial in an obscure little town, but it also embodied the “politics-driving-curriculum” debates that are defining America today. Forty years after his trial, Scopes looked back at his headline-grabbing trial and declared “that restrictive legislation on academic freedom is forever a thing of the past.”

Today, his optimism seems naive as state legislators and local school boards are working to prohibit teaching Critical Race Theory. The current battles look remarkably similar to the panic over evolution, or “Darwinism,” as it was dubbed, that began a century ago. The American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten called the current preoccupation with CRT a “modern-day Scopes trial.”

Yet Darwinism (similarly to CRT) had been around for about half a century. English scientist Charles Darwin had published his signature work, “On the Origin of Species,” in 1859. While religious leaders criticized his ideas about evolution from the very beginning, there weren’t anti-evolution laws because Darwinism hadn’t substantially affected the way science was taught in schools. What made it suddenly become a major target of organized political opposition?

In the late 1910s, a new generation of life science textbooks, mostly written by teachers, developed a new unified course of study—biology—that pulled from disciplines like zoology and botany to focus on core concepts applicable to all living organisms such as metabolism, evolution, cellular theory and heredity.

Those who feared the demographic, economic, and social changes taking place in the United States at that time claimed that reformers were against the Bible. By implying that compulsory schooling of their children violated their religious freedom, anti-evolutionists put education reformers and science advocates on the defensive. Public schools became the platform for opposing a transition to a new cultural and economic vision of America.

Darwinism became a convenient symbol for broader opposition to changes in American society and anti-evolutionists defined the terms of debate for decades. But rejecting education seemed like embracing ignorance. It wasn’t until the 1950’s and 60’s, when the space race and the Cold War became central concerns, that scientists began showing the negative economic and national security impacts of hostility to science education.

If this rhetorical strategy seems familiar, it’s because much the same thing is happening in 2021 with CRT. The anti-CRT movement is gaining traction at another moment of profound demographic, economic, and social change. History reminds us of the need to take such attacks seriously and see them as efforts to advance a broader political agenda, not simply an invitation to engage in debate about curriculum.

THE IMPACT ON EDUCATION

The charge that schools are indoctrinating students in a harmful theory or political mindset is a longstanding one. In the early and mid-20th century, public concern about socialism or Marxism grew. The conservative American Legion, beginning in the 1930s, sought to rid schools of progressive-minded textbooks that encouraged students to consider economic inequality; two decades later the John Birch Society raised similar criticisms about school materials. As with CRT criticisms, the fear was that students would be somehow harmed by exposure to these ideas.

Critical Race Theory appears to be the latest salvo in this ongoing debate, with teachers caught in the middle of this latest culture war.

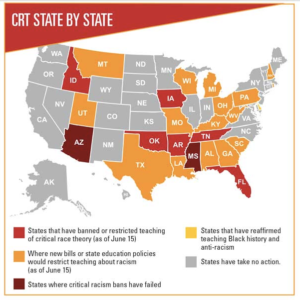

As of July 15, 2021, six states had banned the teaching of critical race theory, and 26 states have introduced bills or taken other steps to restrict teaching CRT and/or impose limits on how race is discussed in the classroom, according to an Education Week analysis. Eleven states have enacted these bans, either through legislation or other avenues. And only Delaware has reaffirmed teaching Black history and anti-racism.

To search for details about your state’s actions on critical race theory, click here.

Much of the current debate appears to spring not from the academic texts, but from fear among critics that students—especially White students—will be exposed to supposedly damaging or self-demoralizing ideas. Critics believe that critical race theory will divide Americans, while proponents believe examining the root cause of disparity in the country, and accepting all of history, is the only way to move forward. Critics charge that teaching the theory leads to negative dynamics, such as a focus on group identity over universal, shared traits; that such teachings divide people into “oppressed” and “oppressor” groups, and urges intolerance.

“It’s because they’re nervous about broad social things, but they’re talking in the language of school and school curriculum,” said one historian of education. “That’s the vocabulary, but the actual grammar is anxiety about shifting social power relations.”

A current example that has fueled much of the recent round of CRT criticism is the New York Times’ 1619 Project, which sought to put the history and effects of enslavement—as well as Black Americans’ contributions to democratic reforms—at the center of American history.

In my newsletter of June 20th I wrote about the importance of Juneteenth. I find it ironic that, at the same time that Congress voted almost overwhelmingly to create the new national holiday, the same senators who voted for the Juneteenth holiday also demanded that the Education Department end its effort to encourage schools to fully explore the history of enslavement saying that the push involved “divisive, radical, and historically-dubious buzzwords and propaganda.” Some of these same senators introduced legislation that would cut federal funding for schools that use lessons based on The 1619 Project. They claim that teachers have adopted tenets of critical race theory and are teaching about race, gender and identity in ways that sow division among students. Some school administrators have said that laws like these would inhibit their efforts to root out racism in schools.

CONCLUSION

In an op-ed by Michael A. Schaffner in The Washington Post, he wrote:

“I believe that the histories of too many Americans have been left untold, while much of the rest has been prettified to make the more privileged among us feel better about ourselves….Examining our faults and shortcomings…shouldn’t divide us or make us hate each other.”

Examining and questioning are basic functions of citizenship. With it comes responsibilities—to immerse ourselves in the fullest version of our history to overcome our imperfections and carry on the eternal struggle for equality, and to remain honest about the virtues and shortfalls of America.

Ideally we can find a way to present these truths without shame for what can’t be changed and with an invitation to reflect on today’s realities in light of the lingering damage. It is quite possible to love this country while allowing for its flaws just as we can love others despite their faults because of their saving virtues. The virtue of the U.S. is in its existential promises—all people are created equal, a democracy is the optimum form of government, and a government of “we the people” is the truest, most effective way to collectively achieve the essential goals of “common defense” and “general welfare.” We have fallen short on these promises but it’s the commitment to these promises that makes us Americans.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In next week’s newsletter, I’ll share some of the impacts of the critical race theory debate on our nation’s teachers.