Combating Racism – Reforming Cash Bail

In November 2020, I wrote a newsletter focused on the issue of cash bail and ways to reform pretrial justice. But until I read Emily Brazelon’s Charged: The New Movement to Transform American Prosecution and End Mass Incarceration I didn’t know about the role of prosecutors in pretrial detention for those who cannot afford cash bail. Her book enabled me to see the challenges of our country’s cash bail system in a new way.

The U.S. Constitution protects against “excessive bail.” The first part of the 8th Amendment reads “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed . . .” In 1951, in Stack v Boyle, the Supreme Court said that bail may be set only as high as “reasonably calculated” to ensure the reappearance in court of the accused. Since the standard was vague, it had little impact. In 1966 Congress passed The Bail Reform Act which sought to prevent people from being needlessly jailed “regardless of their financial status.” The number of pretrial detainees dropped by 1/3 between 1962 and 1971.

As crime rose in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s and people became concerned about violence committed by people who were out of jail awaiting trial, Congress amended the Bail Reform Act, instructing federal judges to consider dangerousness in setting bail. In 1987, The U.S. Supreme Court in United States v. Salerno decreed it constitutional to detain someone based on the perception of a future risk of danger. In 2016, nearly 60% of federal defendants were detained before trial (excluding immigration cases) with an average stay of 255 days behind bars.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) estimates that local jail populations grew by 19.8 percent between 2000 and 2014; pretrial detainees accounted for 95 percent of that growth. In mid-2014, the DOJ says, 60 percent of those held in local jails were pretrial detainees.

Of the nearly 740,000 people held pretrial on any given day, about 2/3 are awaiting trial because they can’t afford bail. Over the last two decades, the growth in the jail population has consisted of people detained pre-trial. They have been found guilty of nothing and are supposed to be presumed innocent. The cost of locking them up is nearly $25 million per day. The annual total is $9 billion.

According to 2016 statistics, in Philadelphia, for example, the cost of incarceration in the city’s jail system is $110 to $120 per inmate per day. A 2015 Vera Institute of Justice report noted that Bernalillo County, New Mexico, where Albuquerque is located, spends $85.63 per inmate per day. Johnson City, Kansas reported spending $191.95 per inmate per day.

Pretrial detention because people can’t afford bail falls more heavily on people of color. In a 2017 paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, a group of economists found significant racial bias in the bail decisions of judges in Philadelphia and Miami. The judges were “relying on inaccurate stereotypes that exaggerate the relative danger of releasing Black defendants.” Without a cure, the burden of pretrial detention will continue to fall too often on Black Americans.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

After an arrest, a defendant is entitled to a hearing about whether s/he may go free before trial. At this point everyone is presumed innocent; years can elapse between an arrest and a trial. The decision about who stays in jail and who gets out depends on the amount of bail and whether that amount is affordable. Bail decisions, the first in a long series of decisions, can shape the outcome of a criminal case and even the rest of a defendant’s life. This decision is often made in a few minutes or less, based on the scant information presented early on in an arraignment hearing. Prosecutors draw on the facts in the arrest warrant and rap sheet, reducing the defendant to the police account of what he or she did wrong.

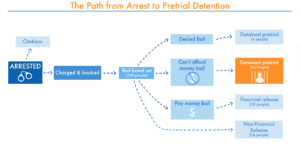

This chart, from the Prison Policy Initiative illustrates the possible paths from arrest to pretrial detention. Almost all defendants will have the opportunity to be released pretrial if they meet certain conditions, and only a very small number of defendants will be denied a bail bond, mainly because a court finds that individual to be dangerous or a flight risk. National data on pretrial detention comes from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties series.

According to Chesa Boudin, a deputy public defender in San Francisco, “What we see literally every day is judges and prosecutors offer our clients ‘credit for time served’ plea deals. If you plead guilty, you get out of jail today. If you assert your innocence, you’re staying in jail. To see that sort of coercive pressure exerted on people to waive their constitutional rights because they’re too poor to pay for their freedom is unbelievably frustrating.”

Prosecutors don’t set the bail, but they make the demands for it that judges accept. Judges can release a defendant arrested for a petty offense when a prosecutor requests bail less than $1,000 because that bail amount signals that the case isn’t important. A judge’s fear of political ramifications shouldn’t come into play. But when 90% of state judges have to run for reelection, it’s pretty hard for politics not to have influence. A judge who releases a defendant over the objections of the prosecutor knows that, if something bad happens, s/he will be culpable, so judges rarely do.

Research has found that pretrial detention, a practice intended to protect public safety, can actually lead to more crime. A 2013 study by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, a nonprofit that funds research into social problems, found a strong correlation between the length of pretrial detention and the likelihood of committing more crimes. As detention increases, “the defendant’s place in the community becomes more destabilized,” increasing the risk of recidivism.

Another 2013 study by the foundation determined that those held in pretrial detention were more likely to receive prison sentences. The reason: juries tend to believe that defendants in prison are guilty, and prosecutors have greater leverage in making plea deals with defendants who are jailed.

AN EXAMPLE OF THE PROBLEM: HARRIS COUNTY, TEXAS

In 2015, Sandra Bland, was 28 years old when she died in a Harris County, Texas jail after being pulled over for a traffic stop and couldn’t afford to pay her bail. In May 2016, Maranda Odonnell, a single mother was held for two days on a charge of driving with a suspended license because she couldn’t afford the $2,500 bail. Harris County contains Houston, America’s fourth largest city by population. Public interest groups sued the county on behalf of people who couldn’t make bail for offenses like driving without a license. Their suit included videos of hearing officers setting bail in a matter of seconds, without a defense lawyer present.

In May 2017, Judge Lee Rosenthal declared Harris County’s misdemeanor bail system unconstitutional, saying “holding un-adjudicated minor offenders in the Harris County jail solely because they lack the money or other means of posting bail is counterproductive to the goal of seeing that justice is done.” In addition, it violates the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment. By relying on cash bail, she wrote, “the system permits offenders their freedom according to what they can afford, rather than the seriousness of their crimes or their flight risk.” One major problem with cash bond is the potential public safety threat created by letting wealthier people go free even if they could be dangerous.

The biggest-ever bail study was conducted in 2016 by researchers affiliated with the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. They studied more than 380,000 misdemeanor cases in Harris County (Houston and its suburbs) and found that misdemeanor defendants who were detained pretrial were 30% more likely to commit a new felony in the 18 months after a bail hearing than the people who were released. They were also 20% more likely to commit a new misdemeanor. They found that locking people up makes them prone, on average, to reoffending. After losing their jobs, housing, and a sense of stability, they are worse off to the point of desperation.

They concluded that, if the 40,000 people in Harris County who couldn’t make bail of $500 had been released instead of held, the state could have prevented 4,000 new crimes. Instead, it spent $20 million on 400,000 days of counterproductive incarceration.

REFORM MOVEMENT

There has been progress in some parts of the country.

Washington, DC eliminated money bail in 1992. Since then, 88% of those who are released make every court appearance. In Kentucky, which also largely does not use money bail, the rate of return to court is 85%. Of the defendants who are released pre-trial in Washington, DC, only 1% were arrested for a violent felony while awaiting trial and only 9% were re-arrested for any offense at all. Numbers in Kentucky are the same. In 2013, Kentucky was among the earliest to adopt a pretrial system replacing cash bond with risk assessments and pretrial supervision.

In California, in 2016, a bill was introduced to eliminate money bail. The bail industry fought back. Tokio Marine, Japan’s largest property and casualty company and the corporation that underwrites a large number of U.S. bail bonds, hired a California lobbying group to lobby against the bail reform bill. Groups representing California’s sheriffs and police chiefs, and the California District Attorneys Association joined the campaign. It was later discovered that California’s attorney general, Xavier Becerra had received $11,000 in donations from bail companies.

Then in January 2018 a California appeals court heard the case of a man who’d been charged with stealing $5 and a bottle of cologne from his neighbor in their senior housing complex. The man sat in jail for more than 250 days because he couldn’t pay the $350,000 bail that had been set. Later that year, California passed a new bill, different from the 2016 bill, that eliminated money bail and released people accused of low-level misdemeanors within 12 hours.

On January 1, 2017, New Jersey also essentially eliminated cash bail. In campaigning for New Jersey’s bill, the state’s Drug Policy Alliance showed that on a single day, more than 1,500 people were in jail in New Jersey because they couldn’t afford to pay bail of $2,500 or less. In the first year after passage of the law, the jail population decreased significantly while crime, including violent offenses, also fell. Then in 2014, New Jersey voters agreed to a pretrial system of risk assessments and pretrial supervision.

The New York City Criminal Justice Agency (CJA) sent observers to more than 2,000 bail hearings in Brooklyn and Manhattan during 2003. According to Bazelon, they found that “the prosecution’s bail request was the only important factor in the amount of bail set.” The CJA found that their recommendations predicting the risk of flight and re-arrest were more accurate than prosecutors’ recommendations on average. But to judges, that didn’t matter.

RISK ASSESSMENT ALTERNATIVES

Federal courts have used a pretrial risk assessment system, followed by pretrial services that ensure defendants show up to court, since the 1960’s. Risk assessment questions examine the defendant’s criminal history, current charge and personal circumstances. (e.g., the seriousness of the charges, whether s/he has failed to appear in the past, homeownership and employment status, and any strong ties to a foreign country). Those released get pretrial supervision—regular check-ins with an agent, telephone reminders for court dates, and drug treatment and ankle monitors where necessary. In the federal system, the cost of pretrial services was $8.98 per person per day in 2014, as opposed to $76.25 per person per day for pretrial detention.

In 2015, New York City announced it was replacing money bond for low-risk defendants with text reminders to appear in court and counseling as appropriate. Then in January 2020, as CJA’s revised assessment was nearing completion, the New York State legislature passed sweeping criminal justice bail reform legislation. This reform—effective January 1, 2020—eliminates the use of money bail for most misdemeanor and non-violent felony offenses, specifies the presumptive use of appearance tickets by law enforcement officers for many charges, and includes specifications for the use of assessment tools in release decisions.

BOND COMPANIES

The U.S. and the Philippines are the only countries in the world that allow for-profit bond companies to operate. New York Times reporter, Adam Liptak wrote that “agreeing to pay a defendant’s bond in exchange for money is a crime akin to witness tampering or bribing a juror—a form of obstruction of justice.” Handing over bail to privates businesses, which charge a nonrefundable fee, invites price gouging and bounty hunting. It contributes to corruption, giving private companies an incentive to collude with prosecutors and judges to make sure that bail is set high.

American bail businesses collect an estimated $2 billion in profits annually. The bonds they issue are increasingly underwritten by a small number of multinational corporations such as Tokio Marine, Japan’s largest property and casualty insurer.

In a 2004 study in the Journal of Law and Economics, defendants who used a bail bond company were found to be 28% less likely to fail to appear in court than those released on their own recognizance. The probability of becoming a fugitive was also 64% lower for those using a bail bond company than those paying the court directly. One explanation is that family members, who often stand to lose money or property, have an incentive to prevent the defendant from fleeing.

REFORMING PRETRIAL BAIL

Below is a long list of recommended reforms to the cash bail systems which appeared in my November 2020 newsletter:

- Decriminalize behaviors that are better addressed through public health and community investments, outside the legal system.

- Focus on solving common obstacles to court return.

- Invest in court reminders, free or subsidized transportation to court, and childcare assistance, measures that improve appearance rates.

- Develop effective systems of voluntary referrals to social services and community-based organizations.

- Invest in social services and resources.

- Make nonessential court hearings optional.

- Improve court scheduling and rescheduling practices.

- Institute grace periods for nonappearance before issuing bench warrants.

- Mandate the use of noncustodial citations instead of arrests.

- Let communities decide their most pressing needs and guide investment decisions.

- Ensure transparency so the criminal justice system is accountable to the communities it serves.

- Support The National Bail Out organization [Wendy, please hyperlink just The National Bail Out]

- Support organized efforts to end cash bail by donating to The Bail Project.

- Elect political candidates who are committed to reforming the current cash bail system.

And a new addition to my original list:

- Mandate training for prosecutors and judges to overcome the negative stereotyping and racial biases that lead to greater discrepancies in requiring and setting bail.

To read more details about each of these measures, click here to go to my November, 2020 newsletter on reforming the cash bail system.

Continuing cash bail perpetuates a system in which the constitutional principle of “innocent until proven guilty” really applies only to the well off. Predicating freedom before trial on one’s wealth is just fundamentally unfair to poor people. According to a February, 2019 report in The Tampa Bay Times, money bail is “wealth-based discrimination.” If you are wondering what you can do, below are slightly edited suggestions from last week’s newsletter:

- Investigate the cases and attitudes of the prosecutors and district attorneys in your county or city. You can find information on their website or listen to their campaign speeches. Do they deny that racism permeates the criminal justice system? Do they work to reform cash bail? What is their record of setting cash bail for defendants? Is there any racial disparity in the cash bail amounts they recommend for Black and White defendants for the same crime?

- Spread the word about the prosecutors and district attorneys that are up for election or reelection in your county or city and the importance of prosecutors to reforming our criminal justice system.

- Join or create a community advisory board to work with your local district attorney to bring about prosecutorial reform and cash bail reform.

- Support the ACLU in its efforts to reform the criminal justice system. You can donate here.

- Vote for reform-minded prosecutors in the next election in your state, county or city.