Combating Racism – 19th Century Black Female Authors – Part 3

For the past two weeks I have written about significant, but little remembered 19th century Black female authors. In this final installment in this series, I am including one better-known author (Sojourner Truth) and one 18th century author that I just couldn’t leave out (Phyllis Wheatley). The stories of these women, like those in parts 1 and 2 of this series, inspired me. I hope their stories inspire you as well.

AMANDA BERRY SMITH (1837 – 1915)

Amanda Berry Smith was born into slavery in January, 1837 in Long Green, Maryland. Her parents were slaves, but her father managed to purchase his family’s freedom in 1850. In later years, Smith attended a predominantly White school and was recognized for her great singing voice and impressive vocabulary. She began to sing regularly at area churches and to preach from the pulpit on occasion.

Her first husband was killed during the Civil war. She remarried a church deacon who planned to pursue the ministry. However, his interest in the church quickly waned, while Amanda’s interest increased. She felt a strong pull toward evangelism and devotion to the church. After losing her second husband and all three of their children to illness in 1869, she devoted herself to her religion. In 1878, although not officially ordained as a minister, she became the first Black woman to work internationally as an evangelist. She traveled around the world spreading the Gospel of Christ.

Her autobiography entitled, An Autobiography: The Story of the Lord’s Dealings with Mrs. Amanda Smith the Colored Evangelist, was published in 1893 and discussed her conviction regarding the doctrine of entire sanctification. Her life and ministry left an indelible mark on the Church of God in Christ.

Through book sales, donations, and lecturing fees, she began to raise money for an orphanage for homeless Black girls. She founded a small newspaper, The Helper, to generate publicity and income for the orphanage. In 1899, the orphanage opened its doors. After Smith’s death in 1915, the state of Illinois took over the orphanage which was renamed the Amanda Smith Industrial School for Girls until it was destroyed by a fire in 1918.

SUSAN (SUSIE) BAKER KING TAYLOR (1848 – 1912)

Born in Liberty County, Georgia, on August 6, 1848, Susie Baker was raised enslaved. Her mother was a domestic servant for the Grest family. At the age of 7, Baker and her brother were sent to live with their grandmother in Savannah. Even with the strict laws against formal education of Blacks, they both attended two secret schools taught by Black women. Baker soon became a skilled reader and writer.

Under the watchful eye of her grandmother, who was adamant that they become literate, Susie and her brother would walk half a mile from their house each morning to the home of Mrs. Woodhouse, a friend of their grandmother, to learn reading and writing. The kids wrapped their books in paper to keep the police from seeing them, since literacy was illegal for Blacks in Georgia. After Susie learned all she could from Mrs. Woodhouse, she began taking lessons from a White playmate, and later from the son of her grandmother’s White landlord.

Writing came in handy for Susie almost immediately. She began to write passes for her grandmother and other local Black folks, who needed a pass to legally be out after nine in the evening. Otherwise they were arrested and fined, which, in the case of a slave, meant the slave owner had to pay the fine.

The Civil War brought Baker her freedom but not immediately. On April 1, 1862, at age 14, Baker was sent back to the country to live with her mother around the time Federal forces attacked nearby Fort Pulaski. When the fort was captured by the Union Army, Baker fled with her uncle’s family and other Blacks to Union-occupied St. Simons Island where she claimed her freedom. Since most Blacks did not have an extensive education, word of Baker’s knowledge and intelligence spread among the Army officers on the island.

Five days after her arrival, Baker was offered books and school supplies by Commodore Louis M. Goldsborough if she agreed to organize a school for the children on St. Simon’s Island. Baker accepted and became the first Black teacher to openly instruct Black students in Georgia. By day she taught children and at night she instructed adults. Baker met and married her first husband, Edward King, a Black non-commissioned officer in the Union Army, while teaching at St. Simon Island.

For the next three years, Susie Baker King traveled with her husband’s regiment, working as a laundress while teaching Black Union soldiers how to read and write during their off-duty hours. She also served—without pay or formal training—as a nurse, helping camp doctors care for injured members of the Thirty-third United States Colored Infantry, a Black regiment of Union soldiers. Susie King Taylor became the first Black army nurse in the Civil War.

In 1866, the Kings returned to Savannah, where she established a school for freed Black children. In that same year, Edward King died only a few months after their first son was born. By the early 1870s, she moved to Boston, Massachusetts where she met her second husband, Russell Taylor. With nursing being a passion of hers, Baker soon joined and then became president of the Women’s Relief Corps, which gave assistance to soldiers and hospitals.

In 1890, Baker wrote her memoirs which she privately published in 1902 as Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd US Colored Troops. She was the only Black American woman to publish a memoir of her wartime experiences. She died in 1912.

PRISCILLA JANE THOMPSON (1871 – 1942)

Priscilla Jane Thompson was born in 1871 in Rossmoyne, Ohio, the daughter of two slaves who escaped to freedom on the Underground Railroad. Priscilla’s parents raised her and her siblings to be educated and immersed in the arts.

After school, Thompson trained to be a teacher, but could never teach due to ongoing sufferings from heart disease. She did manage to teach Sunday school at Zion Baptist Church, and began writing and reading her work in the area. She lived with her siblings, including Garland, whose work provided a steady income.

Inspired by the stories of her parents and other Black folks in the Cincinnati area, Thompson wrote cutting verses on slavery and the injustices that survived with abolition. She self-published two books of poetry, Ethiope Lays (1900) and Gleanings of Quiet Hours (1907). The former was featured at the Paris Exposition of 1900 in the “Collection of Colored Literature” and won significant praise. In her introductions, Priscilla made known her intentions for writing: “to bring true Black characters to life with honesty and depth.” She was responding to the stereotypes and racism embedded deep into American society. She fought for the Black woman’s place within the literary world. Her poetry is considered an ode to the wisdom and beauty of the Black woman.

Thompson began showcasing her poetry at expositions where activist Booker T. Washington was often the featured guest. She is considered to have inspired the Harlem Renaissance.

Priscilla died in 1942 of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 71. She was interred at the Colored American Cemetery, or what is now the United American Cemetery. After her death, her work never truly saw widespread admiration.

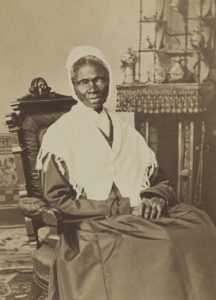

SOJOURNER TRUTH (1797 – 1883)

Sojourner Truth, whose birth name was Isabella “Belle” Baumfree, was born into slavery in Swartkill, New York. She was bought and sold four times, and subjected to harsh physical labor and violent punishments.

In 1806, nine-year-old Baumfree was sold at an auction with a flock of sheep for $100 to John Neely. In 1808 Neely sold her for $105 to tavern keeper Martinus Schryver of Port Ewen, New York, who owned her for 18 months. Schryver then sold her in 1810 to John Dumont of West Park, New York. Dumont raped her repeatedly, creating considerable tension between Baumfree and Dumont’s wife, who harassed her and made her life more difficult.

Late in 1826—less than a year before New York’s law freeing slaves was to take effect—Baumfree escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, Sophia. She had to leave her other children behind because they were not legally freed in the emancipation order until they had served as bound servants into their twenties.

She found her way to the home of abolitionists Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen in New Paltz, who took her and her baby in. Isaac offered to buy her services until the state’s emancipation took effect, which her master accepted for $20. She lived with the Van Wagenens until the New York State Emancipation Act was approved on July 4, 1827. Baumfree had a life-changing religious experience during her stay with the Van Wagenens and became a devout Christian.

Baumfree learned that her son Peter, then five years old, had been sold by John Dumont, and then illegally resold to an owner in Alabama. With the help of the Van Wagenens, she took the issue to court and in 1828, after months of legal proceedings, she got back her son, who had been abused by those who were enslaving him. She became the first Black women to go to court against a White man and win such a case.

In 1829 she moved with her son Peter to New York City, where she worked as a housekeeper for Elijah Pierson, a Christian Evangelist. As an itinerant preacher, Baumfree met abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass. Garrison’s anti-slavery organization encouraged her to give speeches about the evils of slavery.

The year 1843 was a turning point. In addition to becoming a Methodist, on June 1, Pentecost Sunday, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth. She chose the name because she heard the Spirit of God calling on her to preach the truth. She made her way traveling and preaching about the abolition of slavery.

She never learned to read or write. In 1850, she dictated what would become her autobiography—The Narrative of Sojourner Truth—to Olive Gilbert, who assisted in its publication. Truth survived on sales of the book, which also brought her national recognition. She met women’s rights activists, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, as well as temperance advocates, both causes she quickly championed.

In 1851, Truth began a lecture tour that included a women’s rights conference in Akron, Ohio, where she extemporaneously delivered her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech. In it, she challenged prevailing notions of racial and gender inferiority and inequality by reminding listeners of her combined strength (Truth was nearly six feet tall) and female status.

During the 1850’s, she continued speaking nationally and helping slaves escape to freedom. When the Civil War started, Truth recruited young Black men to join the Union cause and organized supplies for Black troops. After the war, she tried unsuccessfully to secure land grants from the federal government for formerly enslaved people (summarized as the promise of “forty acres and a mule”).

After the war, she was honored with an invitation to the White House and became involved with the Freedmen’s Bureau, helping freed slaves find jobs and build new lives. While in Washington, D.C., she lobbied against segregation, and in the mid-1860s, when a streetcar conductor tried to violently block her from riding, she ensured his arrest and won her subsequent case.

Nearly blind and deaf towards the end of her life, Truth spent her final years in Michigan. She continued to fight on behalf of women and Black Americans until her death.

A memorial bust of Truth was unveiled in 2009 in Emancipation Hall in the U.S. Capitol Visitor’s Center. She is the first Black American woman to have a statue in the Capitol building. In 2014, Truth was included in Smithsonian magazine’s list of the “100 Most Significant Americans of All Time”.

BETHANY JOHNSON VENEY (1813 – 1916)

Bethany Johnson (later Veney, because of her second marriage to Frank Veney) was born a slave. She was the daughter of slaves and was born on James Fletcher’s Plantation in Luray, Virginia in 1813. Writing of her early life, Bethany begins her narrative simply: “My mother and her five children were owned by one James Fletcher …. Of my father I know nothing.”

Her mother and master both died when she was about nine years old. Johnson spent about 16 years (ages 14–30) in the household of David Kibler. Though she was owned by Lucy Fletcher the entire time, David Kibler actually had control of her, her daughter, and Miss Lucy. Veney described Kibler as a “Dutchman with a violent temper.” While Miss Lucy hated slavery, she did not know what to do about the way things were, except to be kind to Johnson. Sometime during this stay Johnson began attending a Christian church and eventually became baptized.

Johnson first married Jerry Fickland after their masters consented to the union. Less than a year into their marriage, Fickland was seized and placed in jail. His master, Jonas Menefre, owed a legal debt and his slaves were sold as his assets to a slave trader, Frank White, who took them all South to be sold. The marriage was over.

Bethany Johnson Ficland had a daughter by her first husband and a son by her second husband, Frank Veney. She served a number of different masters, and was separated from her family for a time before being sold in 1850 to the abolition-minded businessman, George James Adams, from Rhode Island. Adams freed her and her son, although she was separated from her second husband, Frank Veney, as a result of the freedom.

At the opening of the Civil War, Adams told her that “she was at liberty to go wherever she pleased.” Veney then went to Worcester, Massachusetts, and one of the first things she recalled doing was making gruel and carrying it to the sick Union soldiers. During this time, she also worked as a laundress and earned extra money by going door to door selling a bluing solution made to brighten clothing. She developed a thriving business selling this solution to housewives of her neighborhood. After the war, she returned to Virginia several times and brought sixteen relatives to Worcester with her, including her daughter Charlotte and Charlotte’s husband, Aaron Jackson. She resided in Worcester for the balance of her life.

Veney published The Narrative of Bethany Veney, a Slave Woman in 1889, over twenty years after slavery was abolished. It includes details of her childhood, incidents that occurred while serving various masters, the way she received her freedom, and her new life in the North. Veney gives a brief account of her own religious conversion and stresses the importance of her faith. The narrative concludes with letters from two clergymen, the first emphasizes the sinfulness of slavery, while the second confirms Bethany Veney’s strength of character.

The value of Veney’s narrative is apparent. According to an annotated bibliography of slave narratives, there are only 29 published narratives that cover the subject of slavery in Virginia between 1784 and 1865. Of that number, only three deal with slavery in the Shenandoah Valley—two being from former Frederick County, Virginia slaves, and one (Bethany Veney) from Shenandoah Co, (later Page Co,) Virginia.

Veney died on February 14, 1921 at the home of her daughter in Worcester. In July 2003, the Governor of Massachusetts, Mitt Romney, signed a proclamation honoring Bethany Veney and her life by declaring the day “Bethany Veney Day” in Worcester, Massachusetts.

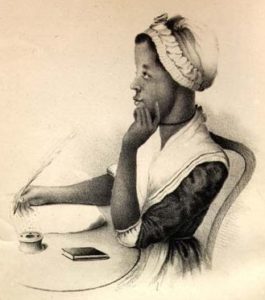

PHILLIS WHEATLEY (1753 – 1784)

Born around 1753 in Senegambia, Africa, Wheatley was captured by slave traders and brought to America in 1761. Upon arrival, she was sold to the Wheatley family in Boston, Massachusetts. Her first name Phillis was derived from the ship that brought her to America, “The Phillis.” The Wheatley family taught her how to read and write and, realizing her talent as a writer, they encouraged her to write poetry at a young age.

Within sixteen months of her arrival in America she could read the Bible, Greek and Latin classics, and British literature. She also studied astronomy and geography. At age fourteen, Wheatley began to write poetry, publishing her first poem in 1767. Publication of “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of the Celebrated Divine George Whitefield” in 1770 brought her great notoriety.

In 1773, with financial support from the English Countess of Huntingdon, Wheatley traveled to London with the Wheatley’s son to publish her first collection of poems, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. With this publication, Wheatley became the first Black American woman to publish a collection of poetry. It included a forward, signed by John Hancock and other Boston notables—as well as a portrait of Wheatley—all designed to prove that the work was indeed written by a Black woman. She was emancipated shortly thereafter.

After receiving praise from early American leaders such as George Washington and other Black writers such as Jupiter Hammon, Wheatley became famous throughout the American colonies and England.

Wheatley’s poems reflected several influences on her life, among them the well-known poets she studied, such as Alexander Pope and Thomas Gray. Pride in her African heritage was also evident. Her writing style embraced the elegy, likely from her African roots, where it was the role of girls to sing and perform funeral dirges. Religion was also a key influence, and it led Protestants in America and England to enjoy her work. Enslavers and abolitionists both read her work; the former to convince the enslaved population to convert, the latter as proof of the intellectual abilities of people of color.

Although she supported the patriots during the American Revolution, Wheatley’s opposition to slavery heightened. She wrote several letters to ministers and others on liberty and freedom. During the peak of her writing career, she wrote a well-received poem praising the appointment of George Washington as the commander of the Continental Army. However, she believed that slavery was the issue that prevented the colonists from achieving true heroism.

In 1778, Wheatley married John Peters, a free Black man from Boston with whom she had three children, though none survived. Efforts to publish a second book of poems failed. To support her family, she worked as a scrubwoman in a boardinghouse while continuing to write poetry. Wheatley died in December 1784, due to complications from childbirth. In addition to making an important contribution to American literature, Wheatley’s literary and artistic talents helped show that African Americans were equally capable, creative, intelligent human beings who benefited from an education. In part, this helped the cause of the abolition movement.

CONCLUSION

The 18 names I’ve written about for these three weeks are just a small sample of the earliest Black American women authors. These women, among others, paved the way for more contemporary authors such as Maya Angelou, Roxane Gay, bell hooks, Tayari Jones, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Jesmyn Ward, to name but a few.

These Black American women authors have brought the Black woman’s experience to life for millions of readers. Their autobiographical accounts reveal the bigotry and discrimination they faced while growing up. To better understand the history of the racial inequality in our country, consider reading these and other works and support the writing of all Black authors. And let me know what you’re reading. I look forward to hearing from you.