Combating Racism – Understanding Racial Violence – Part 1

Anyone who knows me will tell you that I abhor violence. Of any kind. I can’t watch it on TV or in the movies, or read graphic descriptions of racial violence in books or magazines. So it surprises even me that I’m writing this newsletter, the first in a series, about racial violence in America.

An opinion piece in this past Thursday’s Washington Post by Walter Greason entitled, “We must honor those lost to violent racism,” made me realize how little I know about the history of racial violence in our country and inspired me to dig into history. Hence, this and several subsequent newsletters about the topic. Warning: this is an R rated newsletter.

FIRST, SOME DEFINITIONS:

RIOT: a tumultuous disturbance of the public peace by three or more persons assembled together and acting with common intent.

MASSACRE: the act or an instance of killing a number of usually helpless or unresisting human beings under circumstances of atrocity or cruelty.

Regrettably racial violence has been a distinct part of American history since 1660. While that violence has impacted almost every ethnic, racial, and religious group in the United States, it has had a particularly horrific effect on Black life. Listed below are only a few of the major incidents of racial violence that occurred between the Antebellum and Post-Reconstruction eras.

1829 – CINCINNATTI, OHIO

Racism and economic tensions fulminated in Cincinnati, Ohio from August 17-22, 1829, resulting in White violence against Blacks over a two-week period. White mobs invaded the riverfront area where Blacks lived, with the avowed intent to drive them all out of the city.

The violence was rooted in racial animosity exacerbated by competition for jobs. Free Blacks who had escaped slavery in the South arrived in Cincinnati with hopes of safety and economic opportunity. A surge of migration from 1826 to 1829 swelled the numbers of Blacks about 10% of the city’s population. Many of the new arrivals were poor and illiterate, and had to construct flimsy shelters along the riverfronts. There they competed for wage labor jobs with poor Whites. Cincinnati Whites were alarmed at the growth of the Black population in the city, especially those deemed indigent.

From the night of August 15 through August 22, white mobs estimated at up to 300 people rioted in the Fourth Ward, where the majority of the city’s 2,250 Blacks lived. The mob destroyed businesses, burned shelters, residences and other structures, and assaulted Black residents.

In the end, more than half the Black population left Cincinnati. A majority ended up in surrounding towns. Those who stayed behind attempted to rebuild their lives but experienced further white assaults in 1836 and beyond. A number of family groups emigrated to Canada, with some settling in a self-governing community they built in Wilberforce, Ontario.

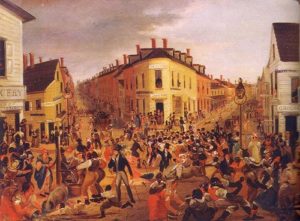

1834 – THE ANTI-ABOLITION RIOTS – FIVE POINTS, NEW YORK

Five Points, New York City

(Public domain image)

In October, 1834 riots broke out in New York City spurred by a confluence of events: the fiery oratory of abolitionist Protestant ministers; the growing social assertiveness of former enslaved people and of free-born Blacks in the city; the growth of Jacksonian democracy which lauded working class White males; and the influx of Irish Catholics who were coming to the city at the rate of 30,000 per year by the mid-1830’s.

Shortly after Abolitionist Rev. Samuel Cox, the church pastor at the Laight Street Church noted that Jesus himself would have been of “Syrian hue” and thus similar in complexion to Blacks, White working-class mobs began to form. Their first targets were white abolitionists and their homes and churches. Rev. Samuel Cox’s Laight Street Church was attacked and the windows were broken. Next the mob of 3,000 rioters attacked Cox’s home on Charlton Street, smashing fencing and throwing paving stones at the residence. Later in the evening, the crowd surrounded Rev. Henry Ludlow’s church on Spring Street, destroying the organ and pews and pulling down the galleries.

Rioting reached its peak of violence in Five Points, the notorious slum shared by Black and Irish residents. Hand bills circulated urging White residents to place a candle in the window, to escape reprisal by floating mobs bent on attacking Blacks. Homes without a candle were demolished. New York Mayor Cornelius Lawrence called out New York’s National Guard. Armed troops took up strategic positions across town, and in a matter of days the rioters were disbursed and the danger subsided.

1834-1838 PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA

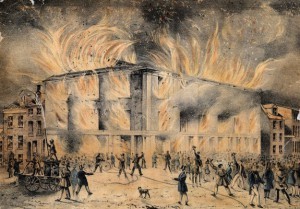

In this dramatic illustration of the burning of Pennsylvania Hall, firefighters douse nearby buildings but do not attempt to extinguish the blaze. (Library Company of Philadelphia)

The Black population in Philadelphia and its surrounding suburbs more than doubled in the first three decades of the nineteenth century, from 6,880 in 1800 to 15,624 in 1830. Coinciding with, but not caused by this growth, was the increase in the abolitionist movement.

These factors combined to create a volatile environment that finally boiled over in the summer of 1834. On August 11, 1834, White and Black citizens quarreled over seats on a merry-go-round known as the “flying horses” near Seventh and South Streets. The next evening, as rumors spread that Black residents had insulted Whites, fighting resulted in the destruction of the carousel. Later that night a group of Whites assembled just outside the Moyamensing quarter, which had a significant portion of Black residents, and moved into the community smashing Black residents’ taverns, homes, and furniture. Nearly twenty rioters were arrested. However, destruction continued over the next two days as White mobs tore down a Black church in Southwark, sacked the First African Presbyterian Church, destroyed more than thirty Black homes, and beat any Black citizen in their path. Despite more than forty arrests and the mayor’s attempt to prevent violence, the underprepared city could do little to prevent the devastation. Minor skirmishes continued over the next few days, but Philadelphia’s first widespread race riot ended on August 14, 1834.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Pennsylvania State Constitution of 1838 rescinded the free Black vote, adding resolve to the fight for Black rights, further intensifying the racial discord of the city and its surrounding suburbs. Abolitionists within the city, not deterred, constructed a meeting hall known as Pennsylvania Hall on Sixth Street near Franklin Square. It opened on Monday May 14, 1838, with national abolitionist leaders such as William Lloyd Garrison, Maria Chapman, and the Grimke sisters in attendance. By Wednesday night a mob gathered outside the building and broke windows as Angelina Grimke spoke to a predominately female audience inside. Although the meeting abruptly ended and the Thursday program was canceled, it was not enough to save the hall. Late Thursday evening a crowd of nearly three thousand gathered in front and set the structure ablaze. After only four days of operation, Pennsylvania Hall burned to the ground as firemen refused to fight the fire and instead focused on protecting neighboring structures.

1863 – DETROIT, MICHIGAN

On March 6, 1863, a White mob attacked Detroit, Michigan’s Black population in the city’s first race riot. As in other Northern cities, many Whites resented the Blacks who had arrived in town, largely from the South. The local Democratic newspaper, the Detroit Free Press, frequently ran articles promoting the idea that freedmen leaving the South would take jobs from White men which in turn heightened racial tension in the city.

Tensions finally boiled over during the trial of William Faulkner, a mixed-race man accused of molesting two girls, one of whom was White. Even though Faulkner identified as a “Spanish-Indian” and had previously voted (at the time, only White men could vote), the Free Press and other newspapers labeled him a Black man. As far as the White public was concerned, Faulkner was Black and had raped a White girl.

When Faulkner was escorted from the courtroom on March 6, a large mob assembled outside the courthouse. Faulkner was convicted and sentenced to life in prison, but the agitated crowd still attacked him as he was transported back to jail. The Detroit Provost Guard, charged with his protection, fired blanks in an attempt to disperse the crowd. The mob fired live ammunition, killing a White bystander named Charles Langer.

Infuriated, the mob set out to attack the city’s predominantly Black neighborhood. They moved in on a cooper shop, and set fire to the shop and an attached home. Although all of the occupants escaped the building, they were immediately attacked by the White mob, and one man, Joshua Boyd, died of his injuries.

In total, the mob burned at least thirty buildings, caused thousands of dollars in damages, and injured many Blacks in the streets. By the time that local troops suppressed the riots, at least 200 Black residents were newly homeless, with some fleeing across the river to Canada.

No one was ever held criminally responsible for the deaths of Langer or Boyd. Several years after the riots, Faulkner’s accusers recanted their story and he was released from prison. Although the Michigan Legislature recommended compensating residents for property damage from the riots, the city council refused to do so.

1866 – MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE

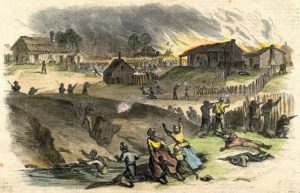

Black Americans attacked in Memphis Riot, May 2, 1866, Harper’s Weekly, May 26, 1866

In the late afternoon of May 1, 1866, long broiling tensions between the residents of southern Memphis erupted into a three day riot known as the Memphis Riot of 1866. The riot began when a White police officer attempted to arrest a Black ex-soldier and an estimated fifty Black veterans, recently mustered out of the Union Army, showed up to stop the police from jailing him. Accounts vary as to who began the shooting, but mobs of White residents and policemen rampaged through Black neighborhoods and the houses of freedmen, attacking and killing Black soldiers. The authority given to the Black soldiers disturbed and discomforted many of Memphis’s White citizens who preferred that the newly freed slaves retain subordinate roles in their city. The victims initially were only Black soldiers, but the violence quickly spread to other Blacks living just south of Memphis who were attacked while their homes, schools, and churches were destroyed. White Northerners who worked as missionaries and school teachers in Black schools were also targeted.

The violence continued throughout the night as the targets now became the Black civilians in the city. Memphis police and firemen openly participated in the violence and looting and as a result the city’s Black citizens could not count on them to stop the attacks or put out the fires in the Black neighborhoods. The conflict stretched into a second day until on the afternoon of the third day, federal troops were sent to quell the violence and peace was restored.

A subsequent report by a joint Congressional Committee detailed the carnage with Blacks suffering most of the injuries and deaths by far: Forty-six Blacks had been killed. Two Whites died in the conflict, one as the result of an accident and another, a policeman, because of a self-inflicted gunshot. Seventy-five Blacks were injured, 5 Black women were raped, and 91 homes, 4 churches and 8 schools (every Black church and school) burned. Over one hundred houses and buildings burned down as a result of the riot and the neglect of the firemen. No arrests were made.

The national impact of the report was the rapid endorsement of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which granted full citizenship to Blacks, and the Reconstruction Act, plus increased Republican majorities in Congress in the November 1866 elections.

1868 – CAMILLA, GEORGIA

The Camilla Massacre, which took place on September 19, 1868, was one of the more violent episodes in Reconstruction Georgia.

Two months earlier, Georgia had fulfilled the requirements of Congress’s Radical Reconstruction plan and been readmitted to the Union. Yet, in early September, the Georgia General Assembly (the state legislature) expelled 28 newly-elected members because they were at least one-eighth Black. Among those removed was southwest Georgia representative Philip Joiner. On September 19th, Joiner led a 25-mile march of several hundred Blacks and a few Whites from Albany to Camilla, the Mitchell County seat, to attend a Republican political rally.

Mitchell County whites were determined that no Republican rally would occur. As marchers entered the courthouse square in Camilla, Whites, quickly deputized by the sheriff and stationed in various storefronts, opened fire, killing about a dozen and wounding possibly 30 others. As marchers retreated into the swamps, hostile Whites assaulted them for several weeks, killing an estimated 15 of the Black rally participants while wounding 40 others, and beating and warning Negroes that they would be killed if they tried to vote in the coming election. The violence at Camilla intimidated some Blacks from voting. White Democrats, then the racial minority in southwest Georgia, carried the election. The Camilla Massacre was the culmination of smaller acts of anti-Black violence committed by White inhabitants that had plagued southwest Georgia since the end of the Civil War.

The Camilla massacre received national publicity, prompted Congress to return Georgia to military occupation, and was a factor in the 1868 U.S. presidential election. Nevertheless, the massacre remained part of southwest Georgia’s hidden past until 1998, when Camilla residents publicly acknowledged the massacre for the first time and commemorated its victims.

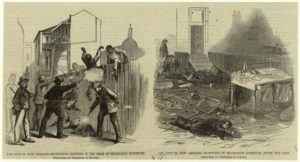

1866 – NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA

The New Orleans Massacre, also known as the New Orleans Race Riot, occurred on July 30, 1866. While the riot was typical of numerous racial conflicts during Reconstruction, this incident had special significance in that it galvanized national opposition to the moderate Reconstruction policies of President Andrew Johnson.

The riot took place outside the Mechanics Institute in New Orleans as Black and White delegates attended the Louisiana Constitutional Convention. The Convention had reconvened because the Louisiana state legislature had recently passed the Black codes and refused to extend voting rights to Black men. Two months earlier, four years of Union Army imposed martial law ended and Mayor John T. Monroe, an active supporter of the Confederacy, was reinstated as acting mayor.

As a delegation of 130 Black New Orleans residents marched behind the U.S. flag toward the Mechanics Institute, Mayor Monroe organized and led a mob of ex-Confederates, White supremacists, and members of the New Orleans Police Force to the Institute to block their way. The mayor claimed their intent was to put down any unrest that might come from the Convention but the real reason was to prevent the delegates from meeting.

Once the delegates reached the Institute, the police and white mob members attacked them, beating some of the marchers while others rushed inside the building for safety. The police and mob surrounded the Institute and opened fire on the building, shooting indiscriminately into the windows. Then the mob rushed into the building and began to fire into the crowd of mostly unarmed delegates.

Some delegates attempted to flee or surrender. Some of those who surrendered, mostly Blacks, were killed on the spot. Those who ran were chased as the killing spread over several blocks around the Institute. Blacks were shot on the street or pulled off of streetcars to be summarily beaten or killed. By the end of the massacre, at least 200 Black Union war veterans were killed, including forty delegates at the Convention. Altogether 238 people were killed and 46 were wounded.

The riot’s repercussions extended far beyond New Orleans. Northerners angry over the violence helped the Republican Party take control of the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate in the Congressional elections of 1866. That Republican controlled Congress subsequently passed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, a series of measures that called for Army occupation of ten former Confederate states and that ensured voting rights for Black men. Meanwhile martial law was immediately re-imposed in New Orleans after the riot and Mayor Monroe and other city officials were forcibly removed from office for their part in the massacre.

1868 – OPELOUSAS, GEORGIA

In September 1868, Southern White Democrats hunted down around 200 Blacks in an effort to suppress voter turnout. It is considered the deadliest massacre in Reconstruction-era Louisiana.

So read the note found on the schoolhouse door in early September by its intended recipient: Emerson Bentley, an 18-year-old White school teacher and one of the few White Republicans in the Louisiana parish of St. Landry. Bentley was teaching Black children in Louisiana while also working as one of the editors of the Republican paper The St. Landry Progress. He and others came to the region to assist recently emancipated Blacks to find jobs, access education, and become politically active. Louisiana had just passed a new state constitution in April 1868 that included male enfranchisement and access to state schools regardless of color.

But southern White Democrats were unwilling to concede the power they’d held for decades before the Civil War. In St. Landry, one of the largest and most populous parishes in the state, thousands of White men were eager to take up arms to defend their political power.

The summer of 1868 was a tumultuous one. With the help of tens of thousands of Black citizens who finally had the right to vote, Republicans handily won local and state elections that spring. But the votes Blacks cast for those elections cost them. Over the summer, armed White men harassed Black families, shot at them outside of Opelousas (the largest city in St. Landry Parish), and killed men, women and children with impunity.

Secret Democratic organizations formed and armed. Organizations like The Knights of the White Camellia, The Ku-Klux Klan, and The Innocents nightly paraded the streets of New Orleans and the roads in the country parishes, producing terror among the Republicans and instigating a wave of violence that erupted on September 28, 1868.

Democrats John Williams, James R. Dickson and Constable Sebastian May visited Bentley’s schoolhouse to make good on the anonymous threats of the earlier September note. They savagely beat Bentley, sending the children who were sitting for lessons scattering in terror.

On the first night, only one small group of armed Blacks assembled to deal with the report they’d heard about Bentley. They were met by an armed group of White men, mounted on horses, outside Opelousas. Bloodshed continued for two weeks, with Black families killed in their homes, shot in public, and chased down by vigilante groups. C.E. Durand, the other editor of the St. Landry Progress, was murdered in the early days of the massacre and his body displayed outside the Opelousas drug store. By the end of the two weeks, estimates of the number killed were around 250 people, the vast majority of them Black.

Democratic papers—the only remaining sources of news in the region, as all Republican presses had been burned—downplayed the horrific violence.

Given that it was the deadliest instance of racial violence during the Reconstruction period, the Opelousas massacre is little remembered today. Only slightly better known is the 1873 Colfax massacre in which an estimated 60 to 150 people were killed—a massacre largely following the pattern set by Opelousas.

1873 – COLFAX, LOUISIANA

The Colfax Massacre occurred on April 13, 1873 in the small town of Colfax, Louisiana as a clash between Blacks and Whites.

Following the hotly contested Louisiana governor’s race of 1872, in which Republicans narrowly won the contest and retained control of the state, White Democrats, angry over the defeat, vowed revenge. In Colfax Parish (county) as in other areas of the state, they organized a white militia to directly challenge the mostly Black state militia under the control of the governor.

On March 28, local White Democratic leaders called for armed supporters to help them take the Colfax Parish Courthouse from the Black and White GOP officeholders on April 1. The Republicans responded by urging their mostly Black supporters to defend them. Although nothing happened on April 1, the next day fighting erupted between the two groups.

On April 13, Easter Sunday, more than 300 armed White men, including members of white supremacist organizations such as the Knights of White Camellia and the Ku Klux Klan, attacked the Courthouse building. When the militia maneuvered a cannon to fire on the Courthouse, some of the sixty Black defenders fled while others surrendered. When the leader of the attackers was accidentally shot by one of his own men, the White militia responded by shooting the Black prisoners. Those who were wounded in the earlier battle, particularly Black militia members, were singled out for execution The indiscriminate killing spread to Blacks who had not been at the courthouse and continued into the night.

All told, approximately 150 Blacks were killed, including 48 who were murdered after the battle. Only three Whites were killed, and few were injured in the largely one-sided battle of Colfax.

A total of 97 White militia men were arrested and charged with violation of the U.S. Enforcement Act of 1870 (also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act). A handful of them were convicted but were eventually released in 1875 when the U.S. Supreme Court in United States v. Cruikshank ruled the Enforcement Act was unconstitutional. No one was ever arrested by the state of Louisiana or by intimidated local officials.

1871 – MERIDIAN, MISSISSIPPI

The Meridian Race Riot occurred over three days in March 1871, resulting in the murders of a White Republican judge and nearly thirty Blacks by a mob of vigilante Whites led by the Ku Klux Klan. The riot is the bloodiest day in the city’s history since the Civil War.

Racial tensions had been brewing in Meridian for some time as White Democrats resented the growing political power of the newly freed Blacks and the growing number of White Republican northerners in the region who were sympathetic to the Black cause. In February 1871, Daniel Price, a White Republican teacher at an all-Black school in Meridian, was arrested after he disguised himself as a Klansman and assaulted a bounty hunter from Alabama who had come to illegally arrest Black workers accused of breaking their labor contracts and fleeing to Meridian. Price was arrested and charged under the anti-KKK legislation with assault while disguised. Ironically, the law had never been used to actually prosecute any Klansmen for violence against Blacks. Tensions escalated as a number of armed Whites from Alabama arrived in Meridian waiting for Price’s trial.

Racial hostilities intensified as the deaths of four Black city officeholders and other Black Meridian residents went unpunished. The Saturday prior to the riot, a public meeting to support Mayor Stirgus was held on the steps of the Lauderdale County Courthouse in Meridian. Black Republican leaders J. Aaron Moore, William Clopton and Warren Tyler, along with the mayor, urged calm. After the meeting, a store owned by the Mayor’s brother was set on fire; the fire spread, burning nearly two-thirds of the downtown area before it was extinguished. Although it was not clear what caused the fire, a rumor spread that Blacks would burn the entire city that night. A mob of angry Whites led a search for Moore, Clopton, and Tyler, who were all arrested and charged with arson and inciting a riot.

Two days later on Monday, March 6, 1871, over two hundred Blacks and Whites—including armed Klansmen—packed the courtroom at the Con Sheehan Courthouse where Moore, Clapton and Tyler — the Black leaders — were put on trial. When Warren Tyler, one of the accused, interrupted the proceedings to contradict the testimony of a White witness, who was on the stand. Enraged at being called a liar, the White man grabbed the billy club that belonged to the city marshal and rushed towards Tyler. At that point, the Meridian race riot began. A shootout ensued and the presiding Republican judge and several others in the courtroom were killed.

Tyler was chased down and shot to death by a White mob. Clopton, who was badly wounded and thrown out of the second floor window of the courthouse during the shootout, died later that night after his throat was cut while he was under the protection of White guards in the sheriff’s office. Moore escaped to Jackson, Mississippi after being chased by a White mob. For the next two days, the angry mob led by the Klan terrorized the citizens of Meridian and killed nearly thirty other Blacks. Mayor Stirgus, who went into hiding, was forced to resign his seat and flee the city.

No one was ever convicted of a crime. Fearing for their own safety, hundreds of Blacks left Meridian. As there was no criminal action taken against anyone in the Meridian race riot, racial violence, led by the Klan, spread throughout the South.

1876- HAMBURG, SOUTH CAROLINA

The Hamburg Massacre (or Red Shirt Massacre) was a key event in the town of Hamburg in July 1876. It was the first of a series of civil disturbances planned and carried out by White Democrats in the majority-Black Republican Edgefield District, with the goal of suppressing Black voting, disrupting Republican meetings, and suppressing Black Americans’ civil rights through actual and threatened violence.

Beginning with a dispute over free passage on a public road, the massacre was rooted in racial hatred and political motives. Armed White “rifle clubs,” colloquially called the “Red Shirts,” wanted to regain control of state governments and eradicate the civil rights of Black Americans. Over 100 White men attacked about 30 Black servicemen of the National Guard at the armory, killing two as they tried to leave that night. Later that night, the Red Shirts tortured and murdered four of the militia while holding them as prisoners, and wounded several others. Events in Hamburg resulted in the death of one White man and six Black men with several more Blacks being wounded. Although 94 White men were indicted for murder by a coroner’s jury, none were prosecuted.

The events were a catalyst in the overarching violence in the volatile 1876 election campaign. There were other episodes of violence in the months before the election, including an estimated 100 Blacks killed during several days in Ellenton, South Carolina, also in Aiken County. The Southern Democrats “redeemed” the state government and during the remainder of the century, they passed laws to establish single-party White rule, impose legal segregation and “Jim Crow,” and disenfranchise Blacks with a new state constitution adopted in 1895. This exclusion of Blacks from the political system was effectively maintained into the late 1960s.

After these events, many Blacks left Hamburg and it began to decline once more. Disastrous floods in 1927 and following seasons finally forced out the last residents in 1929. In the 21st century, no visible remains exist of the former town of Hamburg, and it is largely covered by a golf course.

1886 – CARROLLTON, MISSISSIPPI

The Carroll County Courthouse, ca. 1886

The Carroll County Courthouse Massacre occurred on March 17, 1886 in Carrollton, the county seat of Carroll County, Mississippi.

The events leading up to the massacre began in January when brothers Ed and Charley Brown, who were part Native American and part Black, spilled molasses they were delivering to a saloon on a White man named Robert Moore. The matter was quickly resolved without incident after Moore confronted the Brown brothers. Still, Moore mentioned the matter to his friend and Carrollton attorney James Liddell, who decided to handle the matter on his own.

On February 12, 1886, Liddell confronted the Brown brothers and accused them of intentionally spilling the molasses on Moore. An argument ensued without physical harm. Later that evening, Liddell confronted the brothers a second time. This time, the argument ended with shots fired and all three men wounded, though not seriously.

Though no one knows who fired the first shot, the Brown brothers pressed charges against Liddell for attempted murder. The Whites in Carrollton were angered that a Black person actually had the audacity to charge a White person with a crime.

On March 17, 1886, the day of the trial, over fifty armed White men stormed the courtroom and opened fire on the Brown brothers and the other Blacks in attendance. Some Blacks tried to escape by jumping out the second floor windows but were shot by armed White men waiting outside the courthouse. Both Brown brothers were killed along with twenty-one other Blacks during the massacre. It is unknown how many others died later from bullet wounds. All victims of the Carroll County massacre were Black; no Whites were injured.

No one was ever arrested or charged with the murders. Mississippi governor Robert Lowry stated that the “riot” was perpetrated by and was the result of the “conduct of the Negroes.”

Neither local nor state authorities ever conducted an investigation. Besides newspaper reports, there are few written accounts of the massacre. The massacre is rarely discussed and remains a “cold case” to this day.

1898 – WILMINGTON, NORTH CAROLINA

The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 documents the lengths to which Southern White Democrats went to regain political domination of the South after Reconstruction. The politically motivated attack by Whites against the city’s leading Black citizens began on Thursday, November 10th in the predominantly Black city of Wilmington, North Carolina, at that time the state’s largest metropolis. Statewide election returns had recently signaled a shift in power with Democrats taking over the North Carolina State Legislature. The city of Wilmington, however, remained in Republican hands primarily because of its solid base of Black voters. On November 10th, Alfred Moore Waddell, a former Confederate officer and a White supremacist, led a group of townsmen to force the ouster of Wilmington’s city officials.

Waddell relied on an editorial printed in the Black-owned Wilmington Daily Record as the catalyst for the riot. Alex Manly, the editor of the Daily Record, had published an editorial in early November arguing that “poor white men are careless in the matter of protecting their women.” Manly opined that “our experiences among poor white people in the country teaches us that women of that race are not any more particular in the matter of clandestine meetings with colored men than the white men with the colored women.” His public discussion of the taboo subject of interracial sex exposed the reality of sexual exploitation of Black women by White men and challenged the myth of pure-White womanhood.

Forty-eight hours after Manly’s editorial ran, Waddell led 500 White men to the headquarters of the Daily Record on 7th Street. The mob broke out windows and set the building on fire. Manly and other high profile Blacks fled the city; however, at least 14 Blacks were slain that day. When their criminal behavior resulted in neither Federal sanctions nor condemnation from the state, Waddell and his men formalized their control of Wilmington. The posse forced the Republican members of the city council and the mayor to resign and Waddell assumed the mayoral seat. Over the next two years North Carolina passed the “grandfather clause,” as one in a series of laws designed to limit the voting rights of Blacks.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

I, for one, never learned this history in my entire 12 years of public school and 8 years of undergraduate and graduate study, including advanced courses in American Political History. The United States has done comparatively little until quite recently to memorialize its history of significant racial violence and to bring about lasting change. It is time for us to learn and remember our history of racial violence. I look forward to continuing my learnings in the coming weeks and sharing it through these newsletters.