Combating Racism – Lest They be Forgotten – Part 2

Last week I shared stories of 19th century-born Black inventors, scientists and engineers, many of whom had little or no formal education or training, yet made major contributions to our contemporary way of life. This week, I continue that list with men and women whose names start with L through W.

In sharing these stories, I hope to elucidate the many contributions that have been made to our daily lives by Black Americans who overcame racial prejudice to achieve great things. Most of these men and women’s names never appeared in my history books, nor in my readings about American history. Hence, many have been forgotten. I hope this will no longer be the case.

LEWIS H. LATIMER (1848-1928) – CARBON FILAMENT FOR LIGHT BULBS

Inventor Lewis H. Latimer was the son of former slaves who escaped bondage and settled in Boston. In 1857, the Supreme Court, in the famous Dredd Scott case, ruled that Blacks had no rights in federal courts, and slave states no longer had to honor the “once free always free” doctrine. Since Latimer’s father could not prove they were free, even though they had lived in a free state, he fled the family for their security. The necessary funds to obtain the rest of the family’s freedom were secured by Abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass.

During the Civil War, Latimer joined the Union Navy at age 15. After the war, he worked as an office assistant in the patent law firm of Crosby and Gould. There he taught himself drafting and began to experiment with ideas for inventions.

In 1874 Latimer received his first patent for developing the first toilet to be used on passenger railroad cars, called “Water closet for railroad cars.” In all, he was given eight patents. In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell employed Latimer to draft the necessary drawings for his patent application for the telephone.

Latimer eventually worked on electric lights, became superintendent of the incandescent lamp department of the United States Electric Lighting Company, and supervised the installation of light for buildings in the United States and Canada.

In addition, Latimer is known for pursuing a patent on a safety elevator which prevented riders from falling out and into the shaft and an early version of the air conditioner.

While Edison may have invented the concept for the light bulb, Latimer added the carbon filament that made lightbulbs last longer and made them commercially viable.

In 1890 Lewis Latimer published a book entitled Incandescent Lighting: A Practical Description of the Edison System. He also served as chief draftsman for the General Electric/Westinghouse Board of Patent Control when it was established in 1896.

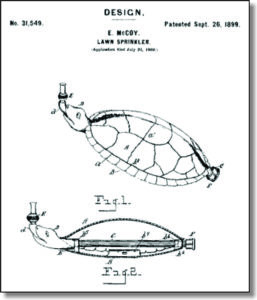

ELIJAH MCCOY (1844-1929) – STEAM ENGINE LUBRICATOR; LAWN SPRINKLER

Elijah McCoy was born in Canada, to fugitive slaves who had escaped from Kentucky to Canada via the Underground Railroad. Beginning at a young age, McCoy showed a strong interest in machines and mechanics. His parents arranged for him to travel to Scotland at the age of 15 for an apprenticeship in mechanical engineering. By the time he completed his training, the Civil War was over, U.S. slaves had been technically freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, and the McCoy family moved back across the border to Ypsilanti, Michigan. McCoy returned home to Michigan after becoming certified as a mechanical engineer.

Despite his qualifications, racial barriers prevented McCoy from finding work as an engineer in the United States. Skilled professional positions were not available to Blacks at the time, regardless of their training or background. McCoy finally accepted a physically demanding and dangerous position as a fireman and oiler for the Michigan Central Railroad. It was in this line of work that he developed his first major inventions.

A railroad fireman typically shoveled two tons of coal into the locomotive’s firebox every hour, and there was no time to rest – if the fire burned out, the train stopped. It was also part of McCoy’s job to monitor the water level in the boiler. If the water level got too low, pressure would build up and could cause an explosion.

Since the friction of steel rubbing against steel at high speeds was so enormous, the train had to be stopped regularly for lubrication of multiple moving parts, including engine parts and the axles, wheels, and bearings of every car. Stopping the train frequently for maintenance was inefficient and expensive. But if lubrications were not performed properly, the results could include fire or derailment. Fire from friction was so frequent that the iconic cupola of the caboose was specifically designed as a surveillance post from which one could watch for smoke or other overheating-related problems.

Elijah McCoy is a classic example of the right man being in the right place at the right time. He was a genius mechanical engineer with a penchant for invention. In addition, he was charged with the physically exhausting job of railroad fireman/oilman, who had to traverse the length of the stopped train to oil all the scorching hot moving parts, some of which were difficult to reach. A White man with international training in engineering would have never found himself working as a railroad fireman and it took both sides of the lubrication issue to invent a more efficient method.

After studying the inefficiencies inherent in the existing system of oiling axles, McCoy invented a lubricating cup that could be fitted into the steam cylinders of a locomotive, distributing oil evenly over the engine’s moving parts, making the job of oiling the train safer and more efficient. After a couple of years of experimentation, in 1872 he obtained a patent for this invention which allowed trains to run continuously for long periods of time without pausing for maintenance.

The Michigan Central Railroad installed his automatic oil cup on their trains. But when other prospective buyers found out that the inventor was Black, they suddenly ignored the product. Other inventors tried and failed to make a product as effective as McCoy’s oil cup. Since the railroad engineers knew McCoy’s oil lubricating cup was the safest and most efficient, and they knew that their lives might depend on it, they often asked whether a locomotive was fitted with “the Real McCoy.”

“Most of the men who insisted on the ‘Real McCoy’ may indeed have been factory owners or railroad owners who discriminated against Blacks in employment, and who never knew that the perfection they sought was the product of the genius of a Black man.”

-Aaron E. Klein, The Hidden Contributors: Black Scientists and Inventors in America

Although McCoy’s achievements were recognized in his own time, his name did not appear on the majority of the products that he devised. Lacking the capital with which to manufacture his lubricators in large numbers, he typically assigned his patent rights to his employers or sold them to investors. In 1920, toward the end of his life, McCoy founded the Elijah McCoy Manufacturing Company to produce lubricators bearing his name.

McCoy went on to revolutionize lawn care by inventing and patenting the first lawn sprinkler – the turtle-shaped lawn sprinkler — and today is widely recognized as the “Father of Turtle-Shaped Irrigation Systems.”

And in response to his wife’s needs, he invented the first folding ironing board.

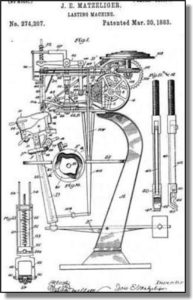

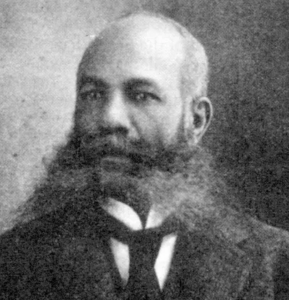

JAN ERNST MATZELIGER (1852-1889) – LASTING MACHINE

Jan Ernst Matzeliger was born in Suriname (South America) of a White engineer father and a Black mother. By the time he turned 10 years old, he was working in his father’s machine shop. There he realized his talent for working with machinery.

At age 19, he left Suriname and worked as a sailor for two years, ultimately settling in Philadelphia where he worked in various trades. In 1876, he moved to Lynn, Massachusetts which, at that time, was the emerging center of the American shoe manufacturing industry. Despite his inability to speak English, he began working in a shoe factory.

In 1883, Matzeliger received a patent for a “Lasting Machine” – a machine that rapidly stitched the leather and sole of a shoe. A skilled hand laster could produce 50 pairs of shoes in a 10-hour day. Matzeliger’s machine could produce between 150 and 700 pairs of shoes a day, cutting shoe prices across the nation in half. His invention made Lynn the “shoe capital of the world.” Nevertheless, his contemporaries referred to him as the “Dutch nigger” and called his invention the “niggerhead laster,” a term used in the apparel industry at that time.

Matzeliger became one of the founders of the Consolidated Lasting Machine Company which was formed around his invention. In 1991, the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Jan Matzeliger.

ALEXANDER MILES (1838-1918 ) – AUTOMATIC ELEVATOR DOORS

Alexander Miles began exploring his passion for inventing, first by creating hair care products while working as a barber in Wisconsin. After settling in Duluth, Minnesota, he began operating a barbershop in the four-story St. Louis Hotel. He became the first Black to become a member of the Duluth Chamber of Commerce.

Before the creation of elevator doors that close automatically, riding a lift was both complicated and risky. People had to manually shut both the shaft and elevator doors before riding. Since many people would forget to do so, there were numerous reported accidents of people falling down elevator shafts. Miles became concerned with the dangerous risks associated with elevators when his daughter almost fell down an elevator shaft. He took it upon himself to develop a solution.

John W. Meaker patented his invention of the first automatic elevator door system in 1874. Thirteen years later (1887) Miles took out a patent for a mechanism that automatically opens and closes elevator shaft doors. It was Miles’ innovation that made electric-powered elevator doors widely accepted around the world. Today, the influence of his patent is present in modern designs for elevator systems in which automatic doors are a standard feature.

In 1899, Miles and his family relocated to Chicago, where he founded The United Brotherhood, an insurance company that sold life insurance primarily to Blacks who could not get coverage from White-owned firms. Due to economic challenges, Miles and his family relocated to Seattle, where he was known to be the wealthiest Black man in the Pacific Northwest region at the time of his death. In 2007, he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

BENJAMIN THORNTON MONTGOMERY (1819-1877) – STEAM-OPERATED PROPELLER

Benjamin Thornton Montgomery was born into slavery in 1819 in Loudoun County, Virginia. In 1837, he was sold south, and purchased in Natchez, Mississippi, by Joseph Emory Davis whose younger brother would later become the President of the Confederate States. Montgomery’s parents were both born in Africa, they were both literate and had access to Joseph Davis’ extensive library. They passed that literacy on to their son.

Davis assigned Montgomery to run the general store of his plantation at Davis Bend. It was unusual for a slave to serve in this position. Impressed with Montgomery’s knowledge and abilities to run the store, Davis placed him in charge of overseeing the entirety of his purchasing and shipping operations on the plantation.

Montgomery learned a variety of skills, including reading, writing, land surveying, flood control, architectural design, machine repair, and steamboat navigation. Montgomery developed proficiencies in many areas; he became a skilled mechanic, not only repairing the advanced agricultural machinery on the Davis plantation, but eventually applied for a patent for his design of a steam-operated propeller to provide propulsion to boats in shallow water.

The propeller could cut into the water at different angles, thus allowing the boat to navigate more easily through shallow water. This was not a new invention, but an improvement on similar designs invented by John Stevens in 1804 and John Ericsson in 1838. On June 10, 1858, on the basis that Benjamin, as a slave, was not a citizen of the United States, and thus could not apply for a patent in his name, he was denied this patent application. The United States Attorney General’s office ruled that neither slaves nor their owners could receive patents on inventions devised by slaves. Later, both Joseph and Jefferson Davis attempted to patent the device in their names but were denied because they were not the “true inventor.” After Jefferson Davis later was selected as President of the Confederacy, he signed into law the legislation that would allow slaves to receive patent protection for their inventions. On June 28, 1864, when slavery was over, Montgomery, no longer a slave, filed a patent application for his device, but the patent office again rejected his application.

Joseph Davis allowed captive Africans on his plantation to retain money earned commercially, so long as they paid him for the labor they would have done as farmworkers. Thus, Montgomery was able to accumulate wealth, run a business, and create a personal library.

GARRETT A. MORGAN (1875 ? -1963) – THE GAS MASK; THE THREE-WAY TRAFFIC SIGNAL

Garrett Augustus Morgan was born in 1875 or 1877 in Paris, Kentucky. (His exact birthdate is unclear.) Garrett received an elementary school education and left home at the age of fourteen, finding work in Cincinnati as a mechanic. In 1895, he moved to Cleveland, where he worked for twelve years repairing sewing machines and in 1901 invented a sewing machine belt fastener.

In 1907, Morgan established his first business, a sewing machine sales and repair shop. He soon expanded with a tailoring business and later the Morgan Skirt Factory employed more than thirty people. His second major discovery came while exploring a way to reduce friction between sewing needles and woolen fabric. He found that a chemical solution he developed to straighten the woolen fibers of textiles also straightened hair. In 1913, he formed the G.A. Morgan Hair Refining Cream Company that sold a line of hair care products.

During the same period, Morgan was working on other projects, including a breathing device that would protect firefighters against smoke inhalation. In 1914, he received a patent for the Morgan Safety Hood and formed the National Safety Device Company. His device was used most notably on July 25, 1916, when he was asked to help rescue 32 Cleveland Water Works miners who were trapped 120 feet beneath Lake Erie during a tunnel collapse. Two previous rescue attempts had failed as rescuers were unable to reach the miners because smoke, dust and fumes blocked their way. The attempted rescuers had become victims themselves. Morgan and his brother and two other volunteers made four trips into the tunnel during the rescue, using the safety masks to descend into the tunnel and saving 8 men and retrieving the bodies of the rescuers that did not survive. Twenty-two men perished in what became known as the “Lake Erie Crib Disaster.” Cleveland newspapers and city officials initially ignored Morgan’s act of heroism and his key role as the provider of the equipment that made the rescue possible. City officials requested the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission to issue medals to several of the men involved in the rescue, but excluded Morgan from their request, an omission suspected of being racially motivated.

Garrett Morgan bringing up a survivor during the Lake Erie Crib Disaster

Even though the contraption had already been proven to save lives, some fire departments cancelled their purchase orders after they found out the inventor was Black. To dodge the effects of prejudice–thereby providing safety for many of the people who denigrated him–Morgan hired a White man to impersonate him.

As an early enthusiast of automobiles, Morgan quickly recognized the need for better traffic control on congested city streets. In 1923, Morgan patented his best-known invention, the three-way traffic signal. After witnessing an accident between a horse-drawn carriage and an automobile, he received a patent for the G. A. Morgan Safety System, an improvement on prior traffic signals that included a caution indicator for all traffic to stop simultaneously. He sold his patent rights for $40,000 to General Electric, which developed an electric version.

During the next decade, Morgan continued to invent while publishing the Cleveland Call, a weekly Black newspaper he established in 1916. It became the Cleveland Call and Post in 1929 and is still in publication today. Other inventions included a women’s hat fastener, a curling comb, and a cigarette extinguisher.

MADAM C. J. WALKER (1867-1919) – HAIR CARE PRODUCTS

Walker was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867, on a cotton plantation near Delta, Louisiana. Her parents were enslaved and recently freed, and Sarah, who was their fifth child, was the first in her family to be free-born. By the age of seven, Sarah was orphaned and went to live with her sister and brother-in-law. When Sarah was 10, the three moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi where Sarah picked cotton and was likely employed doing household work.

At age 14, to escape both her oppressive working environment and the frequent mistreatment she endured at the hands of her brother-in-law, Sarah married Moses McWilliams. On June 6, 1885, Sarah gave birth to a daughter, A’Lelia. When Moses died two years later, Sarah and A’Lelia moved to St. Louis, where Sarah’s brothers had established themselves as barbers. There, Sarah found work as a washerwoman, earning $1.50 a day — enough to send her daughter to the city’s public schools.

She also attended public night school whenever she could. While in St. Louis, Breedlove met husband Charles J. Walker, who worked in advertising and would later help promote her hair care business.

During the 1890s, Sarah developed a scalp disorder that caused her to lose much of her hair, and she started experimenting with both home remedies and store-bought hair care treatments in an effort to improve her condition. During this period, Charles helped her create advertisements for a hair care treatment for Black Americans that she was perfecting and encouraged her to use the more recognizable name “Madam C.J. Walker,” by which she was thereafter known.

In 1907 Walker and her husband traveled around the South and Southeast promoting her products and giving lecture-demonstrations of her “Walker Method” — involving her own formula for pomade, brushing and the use of heated combs.

In 1908 Walker opened a factory and a beauty school in Pittsburgh, and by 1910, when Walker transferred her business operations to Indianapolis, the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company had become wildly successful, with profits that were the modern-day equivalent of several million dollars.

In Indianapolis, the company not only manufactured cosmetics but also trained sales beauticians. These “Walker Agents” became well known throughout Black communities of the United States. In turn, they promoted Walker’s philosophy of “cleanliness and loveliness” as a means of advancing the status of Black women.

Her business acumen led her to be one of the first Black American women to become a self-made millionaire.

Walker quickly immersed herself in the social and political culture of the Harlem Renaissance. She founded philanthropies that included educational scholarships and donations to homes for the elderly, the NAACP, and the National Conference on Lynching, among other organizations focused on improving the lives of Blacks. She also donated the largest amount of money by a Black toward the construction of an Indianapolis YMCA in 1913.

In 1918, at Irvington-on-Hudson — about 20 miles north of New York City — Walker built an Italianate mansion she called Villa Lewaro. It was designed by Vertner Tandy, an accomplished Black architect. Villa Lewaro was a gathering place for many luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

In 1927, the Walker Building, an arts center that Walker had begun work on before her death, was opened in Indianapolis. An important Black cultural center for decades, it is now also a registered National Historic Landmark.

In 1981, the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company ceased operations. Today her company exists under the name Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture and a line of cosmetics and hair-care products bearing the name are available exclusively at Sephora retailers.

In 1998, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp of Walker as part of its “Black Heritage” series.

Walker’s life was portrayed in the 2020 Netflix mini-series, Self Made, with Octavia Spencer portraying Walker.

DANIEL HALE WILLIAMS (1856-1931) – THE FIRST OPEN-HEART SURGERY

Daniel Hale Williams III was a pioneering surgeon best known for performing one of the world’s first successful open heart surgeries in 1893. From 1866 to 1878 he worked as a shoemaker’s apprentice and barber until he decided to pursue his education. In 1878, Williams’s interest in medicine began when he worked in the office of Henry Palmer, a Wisconsin surgeon. In 1880 he enrolled in the Chicago Medical College, receiving a Doctor of Medicine degree three years later.

Immediately after graduation Williams opened his own practice in Chicago and taught anatomy at Chicago Medical College. He became a trailblazer, setting the highest standards of sanitary conditions with regard to germ transmission and prevention, including adopting recently-discovered sterilization procedures.

He also avoided the then-common practice of Black doctors being barred from staff privileges in White hospitals by starting his own hospital. In 1891 Williams co-founded Provident Hospital and Training School Association in a three-story building on Chicago’s South Side. At a time when only 909 Black physicians served 7.5 million Blacks, Provident was the first Black-controlled hospital in the nation. Provident was also the first medical facility to have an interracial staff and the first training facility for Black nurses in the US. During Williams’s tenure as physician-owner (1891-1912), Provident hospital grew, largely due to its extremely high success rate in patient recovery: 87 percent.

In 1893, Williams daringly performed open heart surgery on a young Black man, James Cornish, who had received severe stab wounds in his chest. Despite having a limited array of surgical equipment and medicine, Williams opened Cornish’s chest cavity and operated on his heart. This was the first time a chest cavity had ever been opened without the patient dying from infection. Cornish recovered within 51 days and went on to live for 50 more years.

Now nationally recognized, Williams in 1894 was appointed Chief Surgeon at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. As Chief Surgeon, Williams set high standards for doctors from all over the world, who came to witness his operations. He also reorganized Freedmen’s Hospital which had suffered years of neglect, instituting a training school for Black nurses, employing a multiracial staff, improving surgical procedures, developing ambulance services, and providing staff opportunities for numerous Black physicians.

In 1895 Williams co-founded the National Medical Association (NMA) because Black medical practitioners were denied admission to the all-White American Medical Association. Among the numerous honors and awards bestowed on Williams, perhaps the most groundbreaking was his becoming in 1913 the first Black member of the exclusive American College of Surgeons.

For the next two decades he was a visiting clinical surgeon. From 1907 to 1926, he was invited to work at larger hospitals including Cook County Hospital, and at St. Luke’s Hospital on Chicago’s South Side.

GRANVILLE T. WOODS (1856-1910) – MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS

Woods was born on April 23, 1856 in Columbus, Ohio. He attended school until he was 10 years old and then, as was typical of the era, he left school to start work. Employed in a mechanic’s shop, he developed a fascination with railroad equipment. Woods, an avid reader and astute learner, began to focus all his spare time and attention on mastering electrical engineering. At the age of 20 he enrolled in a technical college and trained for two years in electrical and mechanical engineering. After graduation, with no prominent jobs prospects in Ohio, he worked as an engineer on a British steamer which allowed him to travel the globe. Woods eventually settled Cincinnati, Ohio where he formed the Woods Electric Company. His decision to become an independent entrepreneur stemmed in part because of his difficulty in finding work.

By 1887 Woods developed the first of his inventions, the Synchronous Multiplex Railway Telegraph which allowed communication between moving trains and train depots. One year later he developed a system for overhead electric conducting which helped power locomotives. In 1889 he filed his first patent for an improved steam-boiler furnace.

Woods competed with more prominent inventors of the era including Thomas Edison who claimed invention of the multiplex telegraph and filed a lawsuit to support his claim. Woods won the legal challenge prompting Edison to offer him a prominent position in the engineering department of Edison Electric Light Company in New York. Woods declined the offer, preferring to maintain control over his inventions.

Granville T. Woods developed over 50 significant patents over the course of his life, including a dozen for inventions which made electrical railways safer and more efficient. He was the first Black mechanical and electrical engineer after the Civil War. Because of his significant electrical inventions he is known as the “Black Edison.”

CONCLUSION

This is only a partial list of the many Black men and women whose ingenuity, perseverance and courage over racial prejudice made significant contributions to our daily lives. We owe much to Black scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, and inventors. We take for granted the daily tools that we use – everything from folding ironing boards, to train bathrooms, to airplane devices that signal flight attendants, to dry cleaning, to automatic elevator doors, to three-way stoplights – that were invented by Black Americans.

I have often heard the stereotype of Blacks as lazy or unmotivated. Nothing could be further from the truth in these biographies. Perhaps this and last week’s newsletters will help to dispel that myth.

Remembering these names is one small step to combatting the racism that tarnishes the ideals of our country. Please join me in making their names as familiar as those of Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, George Westinghouse, or Charles Goodyear.