Combating Racism – Combating Voter Suppression – Part 1

How many picture ID’s do you have?

Maybe you have a state-issued driver’s license?

Or an employer-issued photo ID?

Or maybe you have a passport?

But what if you don’t drive and don’t have a driver’s license?

What if you work in a low-wage job where your employer doesn’t require a photo ID?

And what if you have barely enough money to pay your rent, much less need a passport to travel?

Then how would you register to vote?

“I’d get a state-issued non-driver ID,” you might say.

Well, that isn’t as easy as it sounds.

To get a non-driver ID, the Department of Motor Vehicles requires an original birth certificate. Getting a birth certificate can cost as much as $25. Then getting the non-driver identification card can cost as much as $25 in seven states and as little as $10-15 in 16 states. (The cost for a driver ID is as high as $65 in some states.) This also requires the time and transportation to secure the necessary paperwork, luxuries that many Black and lower income Americans do not have. According to a Harvard study, “the expenses for documentation, travel, and waiting time for obtaining voter identification cards . . . typically range from about $75 to $175.” These requirements have an effect on voter turnout.

According to a study done by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) comparing the 2008 and 2012 general elections, in a sample of six states, voter turnout decreased more in the two states with voter-ID laws (Kansas and Tennessee) than in the four without—Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware and Maine. The GAO found that the differences are attributable to voter ID laws.

Voter suppression has a long and ugly history in this country–one that I mistakenly thought we had rectified. From Jim Crow laws to the gutting of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, citizens of the United States, particularly communities of color, have been disenfranchised in blatant and subtle ways.

And over the last two decades it has resurfaced with a vengeance.

THE HISTORY

After the Civil War, three Constitutional Amendments were passed, designed to ensure equality for Blacks in the South. The 13th Amendment, ratified in 1865, abolished slavery and indentured servitude. The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, gave Blacks “equal protection under the laws.” However, it wasn’t until the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, that states were prohibited from disenfranchising voters “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Initially, passage of the 15th Amendment, resulted in high voter turnout among Blacks in the South. In eight Southern states, Black turnout in the 1880 U.S. presidential election was equal to or greater than White turnout. However, Congress did not immediately provide enforcement for the 15th Amendment. At the end of the Reconstruction era, Southern states began implementing policies to suppress Black voters. Unchecked intimidation and the threat of lynching sealed the deal. After 1890, less than 9,000 of Mississippi’s 147,000 eligible Black voters were registered to vote, or about 6%. Louisiana went from 130,000 registered Black voters in 1896 to 1,342 in 1904 (about a 99% decrease). Tennessee was the last state to formally ratify the amendment in 1997.

Below are examples of voter suppression in the United States from the post-Civil War era to the present day.

Poll taxes

Poll taxes were used to disenfranchise voters, particularly Blacks and poor Whites in the South. Poll taxes started in the 1890s, requiring eligible voters to pay a fee before casting a ballot. Eleven Southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia), as well as several outside the South, imposed poll taxes. The poll tax mechanism varied on a state-by-state basis; in Alabama, the poll tax was cumulative, meaning that a man had to pay all poll taxes due from the age of twenty-one onward in order to vote. In other states, poll taxes had to be paid for several years before being eligible to vote. Poll taxes disproportionately affected Black voters—a large population in the antebellum South.

The constitutionality of the poll tax was upheld by the Supreme Court in the 1937 Breedlove v. Suttles and again affirmed in 1951 by a federal court in Butler v. Thompson. As of 1964, five Southern states still employed poll taxes (Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia). The poll tax was officially prohibited in 1964 by the Twenty-fourth Amendment.

Literacy tests

Like poll taxes, literacy tests were primarily used to disenfranchise poor or Black voters in the South. Black literacy rates lagged behind White literacy rates until 1940. Literacy tests were applied unevenly: property owners were often exempt, as well as those who would have had the right to vote (or whose ancestors had the right to vote) in 1867, which was before the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. Black Americans who took these tests were descendants of slaves who were not allowed to read or write in many states due to anti-literacy laws.

White men who could not pass the literacy tests were able to vote due to the “Grandfather Clause” allowing them to vote if their grandfathers voted by 1867. That grandfather clause was ruled unconstitutional in 1915.

Literacy tests varied in difficulty, with Blacks often given more rigorous tests. In Macon County, Alabama in the late 1950s, for example, at least twelve Whites who had not finished elementary school passed the literacy test, while several college-educated Blacks were failed.

Twenty states still had literacy tests after World War II. Literacy tests were outlawed under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and a 1970 amendment to the act prohibited the use of literacy tests for determining voting eligibility.

Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering, also considered another form of voter suppression, is defined by Merriam-Webster as “to divide or arrange (a territorial unit) into election districts in a way that gives one political party an unfair advantage.” Gerrymandering is very much tied into the story of voter suppression even though people often think of it as something a bit different.

Gerrymandering—setting boundaries of electoral districts to favor specific political interests within legislative bodies—often results in districts with convoluted, winding boundaries rather than compact areas, and influences the outcomes of elections by discouraging or preventing significant numbers of people from voting.

Gerrymandering also reinforces racial stereotyping and housing segregation. Politicians capitalize on this disparity by creating fewer districts with high concentrations of minorities to erode representative power of people of color at both the state and federal level.

Many of the newest congressional districts have been drawn in a way that limits the voice and voting power of people of color, which has repercussions for our democracy beyond the violation of personal rights.

Gutting the Voting Rights Act

Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Section 2 of the Act prohibits all states from adopting any “standard, practice, or procedure that results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” Section 4 bans all tests or devices, such as literacy and knowledge tests, moral-character requirements, and the need for vouchers from registered voters. Section 4(b) of the act contained a provision that the 13 southern states with a history of discrimination be required to obtain federal preclearance before changing voting requirements, to prevent further discriminatory laws.

After the passing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, several changes occurred to encourage more people to register to vote.

- Lowering the voting age from 21 to 18 with the ratification of the 26th Amendment during the Vietnam War allowed more men and women across the country to register to vote.

- The National Voter Registration Act of 1993, commonly known as the “Motor Voter Act,” offered more opportunities for voters to become registered by making the Department of Motor Vehicles, public assistance facilities, and disabilities agencies places for people to register to vote.

However, the effort to get more people to vote and the progress after the Voting Rights Act came to a halt after the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court case, Shelby County v. Holder, changed the way the Voting Rights Act was implemented nationwide.

The Court stated that section 4(b) was unconstitutional, determining that this degree of federal involvement in state election law was justified back in 1966, when racial discrimination in voting was rampant in parts of the country and Blacks registered to vote at rates far lower than Whites.

But nearly 50 years later, the Court stated, “Things have changed dramatically. Voter registration rates in covered jurisdictions now approach parity between minorities and non-minorities, blatantly discriminatory voting practices are rare, and minority candidates hold office at unprecedented levels. The literacy tests and low voter registration in the 1960s, have been banned nationwide for more than 40 years and minority voter registration rates have increased dramatically.”

Immediately after the Court’s ruling, significant changes went into effect:

- Texas, Mississippi and Alabama introduced voter identification laws to establish voter eligibility in its 2014 federal election and even though the move was ruled unconstitutional by U. S. District Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos, the U.S. Supreme Court overruled the order.

- Several states implemented polling closures: Arizona and Georgia closed 1 in 5 polling places; Texas closed 1 in 10 polling places, and Louisiana and Mississippi closed 1 in 20 polling places, most of which were in minority neighborhoods.

- In North Carolina, elected officials eliminated same-day registration, scaled back the early voting period, and also implemented a photo identification requirement.

CURRENT ATTEMPTS AT VOTER SUPPRESSION

The Brennan Center for Justice has published a resource listing restrictive and expansive state voting legislation by bill number. It contains our most up-to-date number of voting bills — both restrictive and expansive — in the states as of Feb. 19, 2021. You can find it here.

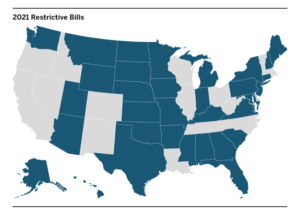

As of February 19, 2021, state lawmakers have carried over, pre-filed, or introduced 253 bills with provisions that restrict voting access in 43 states, and 704 bills with provisions that expand voting access in a different set of 43 states. (In some cases, a single bill can have provisions with both restrictive and expansive effects.)

Legislators in eighteen states have introduced 40 bills to impose new or more stringent voter ID requirements for in-person or mail voting. In ten states that did not require voters to present photo ID at the polls to cast a regular ballot, legislators have introduced bills to impose an ID requirement.

The map below shows those states that have introduced restrictive voting bills. Arizona leads the nation in proposed voter suppression legislation in 2021, with 19 restrictive bills. Pennsylvania comes in second with 14 restrictive policy proposals, followed by Georgia (11 bills), and New Hampshire (10 bills).

In conjunction with the Brennan Center’s report on state voting proposals, below is a list of some of the restrictive bills the Center is tracking to date.

These proposals primarily seek to: (1) limit mail voting access; (2) impose stricter voter ID requirements; (3) slash voter registration opportunities; and (4) enable more aggressive voter roll purges. However, other bills also seek to restrict voting in ways that will disproportionately impact people of color. These bills are an unmistakable response to the unfounded and dangerous lies about fraud that followed the 2020 election.

1) Limitations on early and absentee voting

a) Limiting who can vote by mail:

Fourteen bills in nine states would make the “excuse” requirement more stringent for absentee voting or eliminate “no excuse” mail voting. For example, four different proposals in Pennsylvania seek to eliminate no-excuse mail voting, a policy just adopted with bipartisan support in 2019. Lawmakers in Arizona, Georgia, North Dakota, and Oklahoma also seek to eliminate no-excuse absentee voting.

b) Making it harder to obtain ballots:

Arizona and Pennsylvania have introduced bills that would eliminate the permanent early voter list. Bills in Arizona, Hawaii, and New Jersey would eliminate permanent absentee voting lists, and Florida would reduce the length of time a voter could remain on the absentee list without having to reapply.

Six bills in New Jersey and Arizona would make it easier for officials to remove voters from the permanent absentee list. Nine proposals in seven states would restrict election officials’ ability to send absentee ballots to voters without a specific request. Arizona’s proposal would make it a felony to send an absentee ballot to anyone not on the permanent early voter list.

c) Barriers to completing or casting ballots:

Restrictions on assistance to voters: A single Arizona bill would further restrict who can assist voters in collecting and delivering mail ballots (existing policy already limits such assistance to family and household members).

Witness signatures: Four states have introduced legislation to make it harder to satisfy existing witness requirements. Arizona’s bill would also require all mail ballots to be notarized.

Limitations on absentee ballot return options: Several other states would further restrict ballot return options, including prohibiting mail return and requiring all absentee voters to return their ballots in person. Proposals from lawmakers in Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Virginia would prohibit the use of ballot drop boxes. Missouri and New Hampshire would newly require voters to present identification when returning absentee ballots in person. Arizona’s bill would also add a voter ID requirement for turning in mail ballots in person.

d) Signature matching requirements:

In South Carolina, where a federal court had enjoined signature matching before the November 2020 election, proposed legislation would affirmatively impose a signature matching requirement for absentee ballots. Likewise, in Pennsylvania—there the state Supreme Court ruled that ballots could not be rejected based solely based on mismatched signatures—two proposals would require rejection of absentee ballots on that basis unless the perceived mismatch is cured within six days of notification. A Connecticut bill would also create a signature matching requirement.

e) Changing Ballot receipt & postmark deadlines:

Several states have introduced bills that would require that mail ballots be received earlier in order to be counted, including requiring all ballots not received by Election Day to be rejected. Bills in two additional states (AZ & IA) would impose or advance postmark deadlines. In Iowa, where absentee ballots currently must be postmarked by the day before Election Day, a new bill would require voters to mail their ballots at least ten days before Election Day. Similarly, in Arizona, which does not currently have a postmark requirement, a new bill would reject any ballot postmarked later than Thursday before Election Day, even if the ballot is received by the Election Day deadline.

2) Stricter Identification requirements

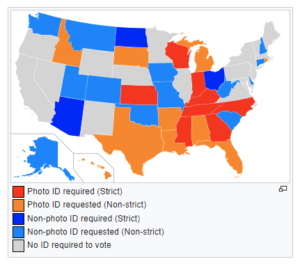

Seven states (see map below) have imposed strict photo ID requirements. Research shows that ID laws disproportionately disenfranchise minority voters. Research also shows that racial minorities are less likely to possess IDs. For example, 7% of White Americans lack driver’s licenses, compared to 10% of Latinos and 21% of Blacks. For unexpired driver’s licenses where the stated address and name exactly match the voter registration record, 16% of White Americans lack a valid license, compared to 27% of Latinos and 37% for Black Americans.

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) provides a web page and a map with voter ID requirements in each state. The map below shows voter ID requirements in each state, based on the five NCSL categories:

3) Reducing Voter Registration Opportunities

Legislators in Arizona, Indiana, Mississippi, and New York have introduced bills requiring voters to produce proof of citizenship in order to register to vote. Meanwhile, Texas lawmakers introduced a bill requiring the secretary of state to send voter registration information to the Department of Public Safety for citizenship verification. Ten bills have been introduced to cut back on opportunities for Election Day registration, with legislators in five states introducing bills to eliminate Election Day registration entirely.

4) Purging voter rolls

Twelve states have introduced 21 different bills that would expand voter roll purges or adopt flawed practices that would risk improper purges. A New Hampshire bill would permit election administrators to remove voters from the rolls based on data provided by other states, a practice that federal courts have found violates the National Voter Registration Act.

5) Voting procedure disinformation

Voting procedure disinformation involves giving voters false information about when and how to vote, leading them to fail to cast valid ballots.

For example, in recall elections for the Wisconsin State Senate in 2011, Americans for Prosperity, a conservative political advocacy group, sent many Democratic voters a mailing that gave an incorrect deadline for returning absentee ballots. Voters who relied on the deadline in the mailing could have sent in their ballots too late for them to be counted. The organization claimed that it was caused by a typographical error.

Just prior to the 2018 elections, The New York Times warned readers of numerous types of deliberate misinformation, sometimes targeting specific voter demographics. These types of disinformation included: a) false information about casting ballots online by email and by text message, b) claims that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents were arresting voters at polling places and included threatening language meant to intimidate Latino voters, c) polling place hoaxes, d) disinformation on remote voting options, e)voting machine malfunction rumors, and f) false voter fraud allegations.

6) Caging lists

Caging lists have been used by political parties to eliminate potential voters registered with other political parties. A political party sends registered mail to addresses of registered voters. If the mail is returned as undeliverable, the mailing organization uses that fact to challenge the registration, arguing that because the voter could not be reached at the address, the registration is fraudulent.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

GEORGIA’S RECENT ACTIONS

This past Monday, the Georgia State House of Representatives passed H.B. 531. The 48-page bill was introduced at 1:53 pm on the Thursday before—only 67 minutes prior to the 3:00 p.m. hearing, allowing Democratic lawmakers and the public no opportunity to review or give an opinion. Some of its provisions include:

- fewer precincts,

- photo ID requirement for mail-in ballots,

- throw out ballots cast in the wrong precinct,

- restrict the use of mail-in ballot drop boxes,

- make “line-warming” (passing out water and snacks to voters waiting in long lines) a crime, and

- fewer hours and weekends to vote (limiting the weekend early-voting period to only one Saturday before election).

This last provision would take away voting opportunities for large, heavily Democratic counties in Atlanta like DeKalb and Fulton, where many Black voters turned out on multiple weekends leading up to the 2020 election. It specifically eliminates early voting on Sundays, when Black churches traditionally hold “Souls to the Polls” get-out-the-vote drives.

In the Georgia January 5th Senate runoff election, Black voters constituted 1/3 of early voters. In the November general election, Black voters used early voting on weekends at a higher rate than Whites in 43 of 50 of the state’s largest counties. These changes particularly target Black voters. During the June primary, voters in predominantly White areas waited six minutes to vote while voters in predominantly Black areas waited 51 minutes to vote.

Georgia Senate Republicans passed their own bill this week (S.B.241) to restrict voting access, including ending no-excuse absentee voting—which 1.3 million voters used in 2020—and adding voter ID requirements for mail-in ballots. The bills were passed by subcommittees of the Senate Ethics Committee at 7 a.m. on Wednesday morning with no public livestream, allowing for little public scrutiny. The State Senate bill would also require vote-by-mail applications to be made under oath, with some requiring additional ID and a witness signature. In Georgia, last Friday, a State Senate committee approved bills to end no-excuse absentee voting and automatic voter registration at motor vehicle offices.

Jim Crow in a suit and tie.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

People of color have long had their political power stripped by voter suppression efforts going back before Reconstruction. Current attempts to thwart the abilities of minorities to cast their votes are reminders of our democracy’s historical failings. But today we have a choice: surrender to the efforts of the many state legislators who are trying to return us to those failings of the past, or fight for an inclusive democracy. Let’s choose the latter.