Combating Racism – Understanding Wealth Inequality – Part 1

Wealth inequality is a serious problem in the United States. Disparities between the wealthiest 1% and the bottom half are far larger in this country than in other democratic capitalist countries. Those who are used to dealing with disparity have only seen their situation worsen because of the pandemic.

The belief that marginalized communities are responsible for their own financial existence is built on the erroneous perspective that wealth inequality is a personal choice problem, not a societal one. Identifying dysfunctional Black behaviors as the basic cause of persistent racial inequality, including the Black-White wealth disparity, ignores our history.

DATA

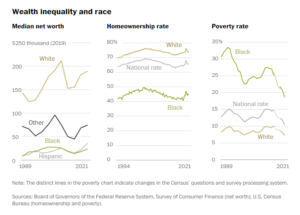

Black families had a median net worth (assets minus debt) of $23,000 as of 2019, compared to $184,000 for White families, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “That’s not a gap, it’s a Black hole,” says Ralph Moore, a veteran consultant in supplier diversity and minority business development.

Data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (2014) shows that Black households hold less than 7 cents on the dollar compared to White households. The White household living near the poverty line typically has about $18,000 in wealth while Black households in similar economic straits typically have median wealth near zero. This means in turn that many Black families have a negative net worth.

As a group, Black families own less than 3% of total household wealth, an amount unchanged from 2016, despite making up 15% of households. White families owned 85% of household wealth but represented 66% of households.

The following charts demonstrate these inequalities.

CAUSES

The legacy of slavery and Jim Crow prevented generations of Black families from building wealth.

Starting in the 1930s, Black families encountered redlining, the practice of mapping Black neighborhoods as a warning to mortgage lenders, isolating them and discouraging investment.

Predatory housing contracts during the 1950s and 1960s siphoned capital from Black families with big markups and punitive terms. These Black families accumulated no equity until their home was paid off and they could easily be evicted.

There were more subtle forces at work, too. The great expansion of wealth in the years after World War II was fueled by public policies such as the GI Bill, which mostly helped White veterans attend college and purchase homes with guaranteed mortgages, building the foundations of an American middle class that largely excluded people of color. Although Black veterans returning from service in World War II were eligible for tuition assistance under the GI Bill, they were barred from enrolling in state universities in the South.

And although Black workers technically were eligible for Social Security benefits, the system barred agricultural workers, who were disproportionately Black. And White families rarely paid Social Security benefits for domestic workers, also disproportionately Black and Hispanic.

In the early 2000s housing bubble, predatory lenders steered low-income families to subprime loans with excessive interest rates, prepayment penalties or other onerous terms that disproportionately hurt Black and Hispanic borrowers.

That legacy hindered opportunities to build wealth through homeownership, or simply building savings.

Moreover, typical Black-owned homes are worth about 37% less than typical homes in the market, according to a report released earlier this year by Zillow.

“At the end of the day, the challenge to home ownership is meeting the underwriting conditions,” says Lowell Ricketts, data scientist at the Institute for Economic Equity. “You need enough wealth for a down payment.”

The outcomes of past injustices are carried forward as wealth is something handed down across generations. Unequal access to assets means unequal opportunities to preserve or increase wealth to be passed on to subsequent generations.

Many popular explanations for racial economic inequality overlook these deep roots, asserting that wealth disparities must be solely the result of individual life choices and personal achievements. The misconception that personal responsibility accounts for the racial wealth gap is an obstacle to the policies that could effectively address racial disparities.

COMMON MISPERCEPTIONS

Our nation’s underlying economic structure is supported by several harmful narratives.

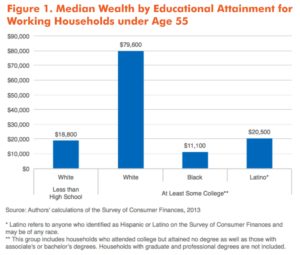

Greater educational attainment will close the racial wealth gap

Higher education is associated with greater household wealth for Americans of every race and ethnicity, yet going to college isn’t enough to overcome racial disparities in wealth. As the figure below shows, Black adults with at least some college had $11,100 in wealth at the median, a figure that is dwarfed by the $79,600 in median wealth held by Whites who attended at least some college.

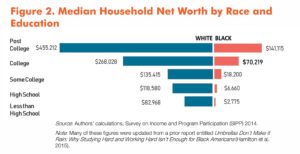

One common sense hypothesis ascribes disparities in wealth mainly to differences in the level of education. A college degree is associated with higher earnings and more stable employment. Higher education has often been touted as the “great equalizer” —as a mechanism to reduce the wealth gap between Whites and Blacks. According to this logic, we would expect Black and Whites with similar levels of education to have comparable levels of wealth.

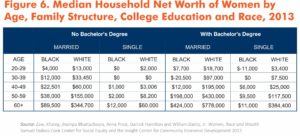

As the figure below shows, for every level of educational attainment, the median wealth among Black families is substantially lower than White families. White households with a bachelor’s degree or post-graduate degree are more than three times as wealthy as Black households with the same degree attainment.

Furthermore, low family wealth can have an adverse effect on the next generation’s educational attainment. Family wealth is a predictor of both college attendance and college completion. A 2016 study found that Blacks are 25% more likely to accumulate student debt and, on average, borrow 10% more to receive the same college degrees as their White counterparts. The adverse implications of this liability are compounded by the fact that Black students are 1/3 less likely to complete their degrees, often because of the greater financial burden that precipitated student loan borrowing in the first place. One study found that 29% of Black students who leave college after their first year do so for financial reasons.

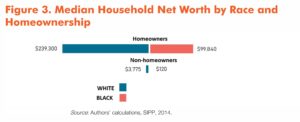

Homeownership among Blacks will close the racial wealth gap

The typical household, regardless of race, holds most of its wealth in home equity. The relationship between housing and family wealth is complex. On the one hand, the ability to purchase a home is a reflection of the wealth a family already has as significant funds are required for a down payment and closing costs. On the other hand, homeownership has also been found to yield strong financial returns on the average and to be a key channel through which families build wealth.

According to 2017 U.S. Census data, 72.5% of Whites own a home compared with 42% of Blacks. Since Black families own homes at substantially lower rates than their White counterparts, some argue that if Blacks achieved rates of home ownership similar to Whites, the racial wealth gap would be eliminated. But the racial homeownership gap does not explain the racial wealth gap.

The figure below shows median household wealth by homeownership rates. Among households that own a home, White households have nearly $140,000 more in net worth than Black households.

The path to homeownership has been riddled with entrenched racism as the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) systematically refused loan applications to Black families through the policy of redlining. According to Richard Rothstein, in The Color of Law,

“Many African American World War II veterans [could] not apply for government-guaranteed mortgages for suburban purchases because…the Veterans Administration would reject them on account of their race . . . . Those veterans then did not gain wealth from home equity appreciation as did White veterans, and their descendants could not inherit that wealth as did White veterans’ descendants. Further, the racialized history of housing policy in the U.S., including residential segregation, redlining, and discriminatory credit practices, have exacerbated inequality in wealth and homeownership rates and have also contributed to the rate of return on the asset itself.”

As illustrated above, even Blacks who own their home encounter a large racial disparity in home values. Furthermore, home equity for Black American homeowners has not increased at the same rate as it has for White homeowners largely because home values in the neighborhoods to which Blacks have been systemically restricted, are lower.

Buying and banking Black will close the racial wealth gap

In his famed 1968 “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, Martin Luther King, Jr. called on his followers to “strengthen Black institutions” by “taking your money out of downtown banks and depositing it in Black owned banks.” The idea that buying and banking from Black owned businesses would empower the Black community and close the racial wealth gap has been widely embraced, including by notables such as Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey, recently in the #BankBlack movement, and by me in previous newsletters.

But Black businesses and banks cannot thrive on a separate and unequal playing field. In the U.S., Black banks are smaller and less profitable than similar White institutions. This is not because the Black-owned institutions lack a strong business model or viable leaders, but because of the economic situation of the communities where they operate and their own disparate levels of access to start up and developmental financing.

Since Black families have minimal liquid wealth, their bank accounts tend to hold money for day-to-day expenses. Small and unstable deposits due to economic penalties forced upon Black workers and households makes profitability a significant challenge for these banks.

For example, in 2016, the top 100 Black-owned firms identified by Black Enterprise collectively grossed $24 billion and employed 73,940 workers. In contrast, Walmart grossed more than 20 times as much in revenue and employed 2.2 million more workers than the entire top 100 Black-owned firms combined. In fact, Walmart, the largest private employer in the U.S., generates more revenue than all 2.58 million Black-owned businesses combined.

Black-owned banks are miniscule in the context of the general scale of American banking. The largest five Black-owned banks recently were estimated to have assets totaling $2.3 billion while J.P. Morgan alone had an estimated $2 trillion in assts. The existing infrastructure of Black-owned banks lacks the capacity to produce wide and substantial increases in Black wealth. And since Black wealth is so low in the first place, it is foolish to anticipate that the existing Black consumer base could build a Black-owned equivalent of J.P. Morgan by banking Black.

In the interest of Black solidarity, the idea of banking Black or buying Black has great merit. But banking Black or buying Black will not do much to reduce the wealth gap in the United States.

Improved earnings will close the racial wealth gap

Wealth is far more unequally distributed than income. While income primarily is earned in the labor market, wealth is built primarily by the transfer of resources across generations, locking in the deep divides we observe across racial groups.

The structural shift from manufacturing to service sector jobs in the U. S. economy had a particularly devastating effect in isolating Black male workers. Some claim that the new service sector jobs require a set of “soft skills” that Black men frequently do not possess, and that, at the individual level, if Blacks simply learn and apply those so-called “soft skills,” earnings and income will improve and thereby close the wealth gap.

The implication that improved earnings and income will close the wealth gaps is a repetition of the conventional trope that individuals should simply apply “personal responsibility” and that will take care of the wealth gap.

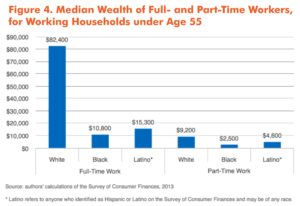

Full-time work is critical to the economic security of most American households. But, as the figure below demonstrates, the median White household that includes a full-time worker has 7.6 times more wealth than the median Black household with a full-time worker and 5.4 times more wealth than the median Latino household with a full-time worker.

Work effort does not pay off equally. According to a study by the Institute on Assets and Social Policy (IASP) of Brandeis University in 2012, White workers employed full time earned a median wage of $792 a week, compared to $621 for Black Americans and $568 for Latinos. Considering gender makes the pay disparities even more glaring: Latina women employed full time earned median weekly wages equal to just 59% of the wages earned by White males, while Black women earned just 68% as much.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, earnings and other types of income are not key determinants of wealth. Personal savings out of earnings and other types of income do not bring about wealth accumulation. An individuals’ striving to get a higher paid job or work more hours is not enough to close the racial wealth gap. The linchpin for wealth accumulation is the transfer of resources across generations, maintaining higher wealth positions among parents and grandparents for their children and grandchildren.

Spending less will close the racial wealth gap

Personal finance experts abound with advice on how to build wealth by moderating personal spending and shifting a greater share of income into savings and investments. Yet, evidence from a recent Duke University study suggests that reducing spending is not enough to close the racial wealth gap between Black and White households.

Drawing on data from the 2013 and 2014 Consumer Expenditure Surveys, researchers found that the average White household spends 1.3 times more than the average Black household of the same income group. The Duke study divided households into low-, medium-, and high-income groups and found that White households in every income group spent more on average than Black households in the same group. On average, White households spent $13,700 per quarter, compared to $8,400 for Black households.

The study also looked at specific categories of spending. The only category in which Black households were found to consistently spend more was for utilities, including payments for electricity, heating fuel, water, sewer, and telephone service. This may be due to the common utility company practice of risk-based pricing, which requires a deposit or other form of additional payment from customers with low credit scores, without stable employment, or with criminal records. While technically color blind, risk-based pricing can have a disproportionate impact on Black consumers, causing them to be charged more than White households for the same service.

Differences in spending habits cannot explain the racial wealth gap. While spending less and saving more may be excellent advice for individuals, the evidence suggests that personal spending habits are not driving the racial wealth cap and cannot succeed in closing it.

Black family disorganization is the cause of the racial wealth gap

Evidence shows that growing up in a two-parent, married home results in significant benefits to children’s outcomes and life chances, including better physical and mental health, higher future wages and social ties, and college completion.

There are substantial differences in living arrangements of children by race and ethnicity. According to the Pew Research Center, 72% of White and 82% of Asian-American children are being raised by two married parents, as are 55% of Latino children. In sharp contrast, only 31% of Black children are living with two married parents while more than 54% are being raised by a single parent.

The increasing rate of single parent households is often invoked to explain growing inequality, and the prevalence of Black single motherhood is often seen as a driver of racial wealth inequities. These explanations confuse consequence and cause and are largely driven by claims that if Blacks change their behavior, they would see marked increases in wealth accumulation. This is a dangerous narrative that is steeped in racist stereotypes.

One explanation for the growing marriage gap between Whites and Blacks and the decline in two-parent families among Blacks is the shortage of marriageable Black men due to higher rates of incarceration and early death.

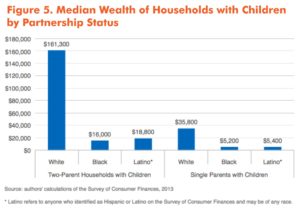

Single motherhood is a reflection of inequality, not a cause. Recent research reveals that the median single-parent White family has more than 2.2 times more wealth of the median Black two-parent household and 1.9 times more wealth than the median Latino two-parent family. The figure below shows that Black and Latino couples with children have a fraction of the median wealth held by White couples with children.

For the last 50 years, American social scientists and policy makers have treated the causes of poverty as largely cultural and focused on single mother families as perpetuating a “culture of poverty.” In 1965, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s report, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, attributed racial inequality as well as poverty and crime in the Black community to family structure, particularly the prevalence of families headed by single mothers. Moynihan racialized and gendered poverty. He viewed the persistence of poverty as due to the disproportionate presence of Black families with female heads. This long-standing narrative still permeates the national discourse and it has often been used to advance the argument that Black families are insufficiently disciplined and responsible to merit better economic conditions.

As shown in the table below, marriage does little to help equalize wealth among White and Black women with a college degree. For example, married White women without a bachelor’s degree have almost two times the wealth of married Black women with a degree.

Family structure does not drive racial inequity and racial inequity persists regardless of family structure. The benefits of intergenerational wealth transfers and other aspects of White privilege benefit White single mothers, enabling them to build significantly more wealth than married parents of color. The economic benefits that are typically associated with marriage will not close the racial wealth gap.

The growing numbers of Black celebrities proves the racial wealth gap is closing

Starting in the early 1980’s, the image of overall Black wealth came to be projected through the lives of a small set of famous Black Americans. From The Cosby Show (which aired on NBC from 1984-1992), to Michael Jackson’s multi-platinum albums, to Will Smith’s meteoric rise, to Oprah Winfrey’s media empire, to the present day mega couple Jay-Z and Beyoncé, Black celebrity has masked Black poverty, rather than contributing to closing the wealth gap. Black celebrity has been placed at the vanguard of an imagined Black achievement of affluence.

The ascendance of Blacks to the most elite positions of society, including Barack Obama’s election to the White House, has furthered the argument of grand racial progress in America. These cases of Black exceptionalism have been held out as examples of what individual or familial acts of perseverance and hard work can achieve and have suggested that all Black Americans finally had arrived at full access to the American dream. Transformative social policies are pushed aside and replaced by what seems easier to attain: individual celebrity status that is presented as a normal and accessible means of access to the “American Dream.” A gap in wealth will not be closed through access to film, music or sports careers.

According to a Bloomberg Business News article titled “Black Executives are Losing Ground at Some Big Banks,” “At JP Morgan Chase & Bo., Citigroup Inc., and Godman Sachs Group Inc., the percentage of senior Black executives and managers fell over the past five years [2012-2017]. The absolute number of Black CEOs of Fortune 500 companies has dwindled from eight in 2015 to four in 2017.

To push toward closing the racial wage gap, the veil of Black celebrity must be pulled back so Americans understand there is no racial meritocracy in wealth, despite what is displayed on television networks.

CONCLUSION

For our nation to begin addressing disparities in wealth and opportunity, we must recognize that the racial wealth gap exists and clearly understand its causes. When asked in a 2016 opinion survey to assess “the financial situation of Blacks compared with Whites today,” just 47% of White respondents, 58% of Black respondents and 47% of Latino respondents recognized that White households were better off financially. When the same survey asked about “reasons why Black people in our country may have a harder time getting ahead than Whites,” majorities of Black, White and Latino Americans endorsed explanations such as “lack of motivation to work hard” and “family instability.”

Racial inequality in wealth is rooted in historic discrimination and perpetuated by policy. The above analyses show that individual behavior is not the driving force behind racial wealth disparities. Building a more equitable society requires a shift in focus away from individual behavior toward addressing structural and institutional racism. Next week I will focus on ways we can move toward a more equitable America.

Sources:

The Asset Value of Whiteness: Understanding the Racial Wealth Gap, Demos, Institute on Assets and Social Policy (IASP), Brandeis University.

What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap, Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equality, Insight Center for Community Economic Development