Combating Racism – Honoring Black History Month 2022 – Part 2

To continue to honor lesser-known Black Americans, this week I am focusing on several civil rights activists whose names may be unfamiliar.

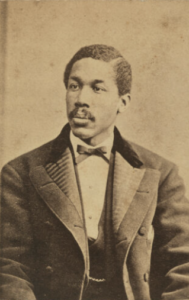

Octavius V. Catto (1839-1871)

Octavius V. Catto was born in Charleston, South Carolina in February 1839. His father was a Presbyterian minister who moved his family to Philadelphia when Octavius was a child. Catto received an excellent education in the city grammar schools, the Academy in Allentown, New Jersey, and finally at the Institute for Colored Youth (ICY) in Philadelphia. The ICY provided a college level of education free of charge to Black youth to prepare them as teachers in Black schools. Catto graduated from the Institute in 1858 as valedictorian and immediately became assistant to the principal. He taught classes in English Literature, Higher Mathematics and Classical Languages. His excellence in teaching became so well known that he was offered the principalship of Black schools in New York and the superintendency of the Black schools in Washington, D.C. He declined those offers choosing to remain in Philadelphia at the Institute.

Catto became more interested in politics, and founded the Equal Rights League in October 1864. He saw political activity as a means to foster betterment for his people. The adoption of the ‘Bill of Rights’ for equal access to public transportation in the city in 1867, and the successful desegregation of Philadelphia’s trolleys, was largely the result of Catto’s urging and activism.

During the Civil War, while still a young man, he was a staunch supporter of the Union, the Lincoln administration, the efforts of the Republican Party to improve civil rights for Blacks and end the scourge of slavery. When the Confederates invaded Pennsylvania in 1863, culminating in the Battle of Gettysburg, a call for emergency troops went out to spur volunteering. One of the first units to volunteer was a company of Black men raised by Octavius Catto, many of whom were Catto’s own students, officered by Whites. Answering the governor’s urgent call for volunteers, they reported for duty. They were uniformed and equipped and sent by train to Harrisburg to join the army. But the authorities there rejected the unit with the excuse that Black troops were not authorized.

Catto, undaunted by the rejection, returned to Philadelphia and threw himself into the effort to raise Black troops to fight for their own emancipation. He joined with Frederick Douglass and other prominent Black leaders to form a Recruitment Committee and was tireless in his efforts to convince young Black men to rally. Under his considerable influence, 11 regiments of ‘Colored Troops’ were organized, trained, equipped, and sent to the war front.

Catto unceasingly pursued the goal of full and equal rights for Blacks. Catto was an eloquent, persuasive and powerful speaker, with a charismatic bearing and impeccable academic credentials. He had a deep and abiding belief in the power of education to improve the status of Blacks, and as a betterment for all citizens. In a January, 1865 speech before the Union League Association, which he had founded to cooperate with the Union League of Philadelphia, Catto said:

“It is the duty of every man, to the extent of his interest and means to provide for the immediate improvement of the four or five millions of ignorant and previously dependent laborers, who will be thrown upon society by the reorganization of the Union. It is for the good of the nation that every element of its people, mingled as they are, shall have a true and intelligent conception of the allegiance due to the established powers.”

Catto’s efforts for equal rights were capped in October, 1870 when Pennsylvania passed the 15th Amendment guaranteeing voting rights for Black men.

The Democratic mayor of Philadelphia, Daniel Fox, and the police force he controlled, exhibited little interest in insuring a peaceful and fair voting procedure in 1871. Fox warned the city that any attempt by the Blacks to vote in the election would be met by violence. In this period, Octavius Catto worked even harder to get out the Black vote, thus ensuring the animosity of the ward thugs and supporters of the Democratic Party.

On Election Day, October 10, 1871, Catto was tireless in his activism, despite the threats and intimidation of his opponents. He continued to work to bring his people to the polls, attempting to calm fears. He went to his 4th Ward voting place and cast his vote. Street violence had already commenced.

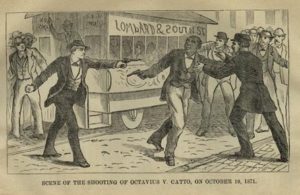

Returning from the polls, Catto could not rely on protection by the police. He set out to return to his home to activate the officers of the Philadelphia Brigade for service in quelling the violence. During the course of the day, four Black men were murdered.

Just a few doors from his home, Frank Kelly, a member of the Moyamensing Hose Company, a Democratic Party operative and an associate of the Party boss, fired two pistol shots into the back of Octavius Catto, one bullet piercing his heart.

The word of Catto’s murder spread rapidly and spurred others, who may have been reluctant to vote, to flock to the polls. Even among many Whites, there was sympathy and indignation at Catto’s murder, and the plight of the Black community. Catto became a martyr to the cause of civil rights. A backlash against the violence turned out a large majority for the Republican ticket, which swept to victory, validating Catto’s cause. A new feeling of acceptance greeted the Black community in the days that followed.

Resolutions were passed appealing for an adoption of Catto’s principles. The largest public funeral in the city since that of Abraham Lincoln was held for him on October 16, 1871. Because Catto was at the time serving in the Pennsylvania National Guard as a Major and Inspector General of the 5th Brigade, and was on duty at the time of his murder, a full military funeral was authorized. Thousands thronged the streets to gain access and a view of the martyred hero.

Catto’s death generated sympathy and acceptance of the voting rights of Blacks, and moved the Black community solidly behind the rising Republican Party. Later, Catto would be honored by the city by having a public school named for him.

Unfortunately, justice was never meted out to Catto’s assassin. Frank Kelly was hidden until he was spirited out of Philadelphia and moved to Chicago. Kelly went unpunished.

Many positive results came from Catto’s assassination. The power of the Democratic Party in Philadelphia and its resistance to equal civil rights was broken. The street gangs, and the hose companies lost influence with the populace. The Republicans began to realize the importance of the Black vote, and more patronage, city office appointments and jobs flowed into the community. Generous donations were bestowed on Black institutions, especially the churches and their ministries. Republican political clubs flourished in the Black wards. Black candidates were nominated and elected to certain city offices.

Octavius Catto, giant of the civil rights movement, defender of his country, educator par excellence, civic activist, and martyr to his cause has been forgotten by all but a few. He has become a role model for all those who strive against injustice and seek a better life. In 2017, a monument to Catto was unveiled at Philadelphia’s City Hall.

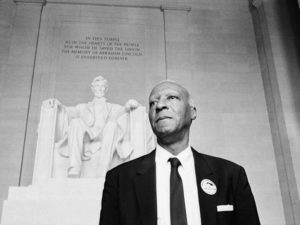

Asa Philip Randolph (1889-1979)

Philip Randolph was born April 15, 1889, in Crescent City, Florida. His father was a minister in an African Methodist Episcopal Church, and his mother a skilled seamstress. In 1891, the family moved to Jacksonville, Florida, which had a thriving, well-established African-American community.

From his father, Randolph learned that color was less important than a person’s character and conduct. From his mother, he learned the importance of education and of defending oneself physically against those who would seek to hurt one or one’s family. Randolph remembered vividly the night his mother sat in the front room of their house with a loaded shotgun across her lap, while his father tucked a pistol under his coat and went off to prevent a mob from lynching a man at the local county jail.

Randolph was a superior student. He attended the Cookman Institute in East Jacksonville, the only academic high school in Florida for Black children. He was valedictorian of the 1907 graduating class. Reading W.E.B. DuBois’ The Souls of Black Folk convinced him that the fight for social equality was most important. Barred by discrimination from all but manual jobs in the South, Randolph moved to New York City in 1911 and took social sciences courses at City College.

In New York, Randolph developed what would become his distinctive form of civil rights activism, which emphasized collective action as a way for Black people to gain legal and economic equality. He and Chandler Owen opened an employment office in Harlem to provide job training for Southern migrants and encourage them to join trade unions.

In 1917, Randolph organized a union of elevator operators in New York City. Two years later he became president of the National Brotherhood of Workers of America, which organized Black shipyard and dock workers in the Tidewater region of Virginia. Although that union dissolved in 1921, he was elected president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) in 1925. After years of bitter struggle with the union, employees gained pay increases, a shorter workweek, and overtime pay.

Through his success with the BSCP, Randolph became one of the most visible spokespeople for civil rights. In 1941 he met Bayard Rustin and along with A. J. Muste, they began to organize a peaceful march of Black Americans on Washington, D.C. to demand an end to racial segregation in the government, and especially the military, and to demand greater equality in the hiring practices of defense industries. Randolph’s belief in the power of peaceful action was inspired partly by Mahatma Gandhi’s success in using such tactics against Britich occupation in India. In May, Randolph issued a “Call to Negro America to March on Washington for Jobs and Equal Participation in National Defense on July 1, 1941.” By June, estimates of the expected marchers reached 100,000. After President Roosevelt failed to persuade Randolph and Rustin to call off the demonstration, he issued Executive Order 8802 barring discrimination in defense industries and federal bureaus (the Fair Employment Act). The Fair Employment Act is generally considered an important early civil rights victory and the proposed march was cancelled.

Buoyed by these and other successes, Randolph and other activists continued to press for the rights of Black Americans. In 1947, Randolph, along with colleague Grant Reynolds, renewed efforts to end discrimination in the armed services, forming the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil Disobedience. When President Truman asked Congress for a peacetime draft law, Randolph urged young Black men to refuse to register. Since Truman was vulnerable to defeat in 1948 and needed the support of the growing Black population in northern states, he eventually capitulated. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman abolished racial segregation in the armed forces through Executive Order 9981.

In 1950, along with Roy Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, and, Arnold Aronson, a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council, Randolph founded the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR). The LCCR remains the nation’s oldest, largest and most diverse civil and human rights coalition and has coordinated a national legislative campaign on behalf of every major civil rights law since 1957.

Randolph and Rustin also formed an important alliance with Martin Luther King Jr. In 1957, on the third anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, when schools in the south resisted integration, Randolph organized the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom where nearly 25,000 demonstrators gathered and heard Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his “Give Us the Ballot” speech.

In 1958 and 1959, Randolph organized Youth Marches for Integrated Schools.

Randolph finally realized his vision for a March on Washington on August 28, 1963, which attracted between 200,000 and 300,000 people to the nation’s capital. The rally is often remembered as the high-point of the civil rights movement, and kept the issue in the public consciousness. However, when President Kennedy was assassinated three months later, civil rights legislation was stalled in the Senate. It was not until the following year, under President Lyndon B. Johnson, that the Civil Rights Act was finally passed. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed. Although Martin Luther King’s name is most frequently remembered, the importance of Randolph’s contributions to the civil rights movement cannot be forgotten.

Randolph died in his Manhattan apartment in May, 1979 following years of struggle with a heart condition and high blood pressure.

Bayard Rustin (1912 – 1987)

Bayard Rustin was born 1912 in West Chester, Pennsylvania. Raised a Quaker, his family was engaged in civil rights activism. He attended Wilberforce University, Cheney State Teachers College (now Cheney University of Pennsylvania), both historically Black schools. In 1937 he moved to New York and studied at City College of New York. While living in New York City, he earned a living as a spiritual singer in nightclubs. He was a life-long pacifist, due to his Quaker upbringing.

Early in the 1940’s, Rustin met A. Philip Randolph, the head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Together they began to organize a peaceful march of Black Americans on Washington, D.C. to demand an end to racial segregation in the government, and especially the military and to demand greater equality in the hiring practices of defense industries. After President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 barring discrimination in defense industries and federal bureaus (the Fair Employment Act) the proposed march was called off. During the Second World War he worked with Randolph, fighting against racial discrimination in war-related hiring.

Rustin also participated in several pacifist groups, including the Fellowship of Reconciliation. In April 1947, as a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Rustin and George Houser, the executive secretary of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), organized the “Journey of Reconciliation,” (also called the “First Freedom Ride”) which became a model for the Freedom Rides of the 1960’s. The rides were intended to test the U.S. Supreme Court’s ban on racial discrimination in interstate travel. Black and White riders set out from Washington, D.C., and passed through North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia on the way back to Washington, D.C. Rustin published his journal entries about his experience and the violence against the “Journey” riders.

His commitment to civil and human rights came at a personal cost. He was arrested multiple times and twice went to jail. During the war, he was jailed for two years when he refused to register for the draft. When he took part in protests against the segregated public transit system in 1947, he was arrested in North Carolina for violating state laws regarding segregated seating on public transportation and served twenty-two days on a chain gang. In 1953 he was arrested on a morals charge for publicly engaging in homosexual activity and was sent to jail for 60 days; however, he continued to live as an openly gay man.

In the 1950’s, Philip Randolph arranged for Rustin to meet the young civil rights leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Rustin began working with King as an organizer and strategist in 1955. Rustin taught King about Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violent resistance, advised him on the tactics of civil disobedience, and taught King how to organize peaceful demonstrations and to form alliances with progressive Whites. He assisted King with the boycott of segregated buses in Montgomery, Alabama in 1956.

The protests organized in cities such as Birmingham and Montgomery provoked a violent backlash by police and the local Ku Klux Klan throughout the summer of 1963, which was captured on television and broadcast throughout the nation and the world. Rustin later remarked that Birmingham “was one of television’s finest hours. Evening after evening, television brought into the living-rooms of America the violence, brutality, stupidity, and ugliness of [police commissioner] Eugene “Bull” Connor’s effort to maintain racial segregation.” Partly as a result of the violent spectacle in Birmingham, which was becoming an international embarrassment, the Kennedy administration drafted civil rights legislation aimed at ending Jim Crow once and for all.

Because of their experiences together, when Philip Randolph was named to head the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, he appointed Rustin as Deputy Director and overall logistical planner. Rustin was a key figure in the organization of the March on Washington, at which King delivered his legendary “I Have a Dream” speech on August 28, 1963.

Bayard Rustin was an organizational force behind the burgeoning civil rights movement during the 1950s and 1960s. His life as an openly gay man, however, put him at odds with the cultural norms of the larger society and left him either working behind the scenes or outside of the movement for stretches of time.

In 1965, Rustin and his mentor Randolph co-founded the A. Philip Randolph Institute, a labor organization for Black trade union members. Rustin continued his work within the civil rights and peace movements, and was much in demand as a public speaker.

Rustin received numerous awards and honorary degrees throughout his career. His writings about civil rights were published in the collection Down the Line in 1971 and in Strategies for Freedom in 1976. He continued to speak about the importance of economic equality within the civil rights movement, as well as the need for social rights for gays and lesbians.

With the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, his talents and tireless work were transferred to human rights and the gay rights movement. In the 1970s and 1980s he worked as a human rights and election monitor for Freedom House and also testified on behalf of New York State’s Gay Rights Bill.

Bayard Rustin died from a ruptured appendix on August 24, 1987 at the age of 75.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Next week I will continue to honor little-known Black Americans whose names should not be forgotten.