Combating Racism – Honoring Black History Month 2022 – Part 3

This week I am highlighting three Black Americans who inspired others and whose names have never become household words.

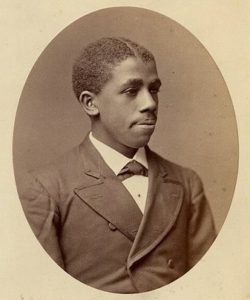

Edward Bouchet (1852–1918)

Edward Bouchet was the son of a formerly enslaved person who had moved to New Haven, Connecticut. His parents were active in their local abolitionist movement and encouraged their son and his three older sisters to gain an education.

Given the segregated public school system, only three schools in New Haven accepted Black students at the time, so Bouchet attended the Artisan Street Colored School which had one teacher and 30 students of all grade levels.

In 1868, he was admitted to Hopkins Grammar School, a prestigious private preparatory school where he studied Latin and Greek, geometry and algebra, and graduated first in his class in 1870.

Later that year he was admitted to Yale University. In 1874 he graduated sixth in a class of 124 students and was nominated to Phi Beta Kappa. He became the first Black person to earn a Ph.D. from an American university and the sixth American of any race to earn a Ph.D. in physics. He wrote a dissertation “On Measuring Refractive Indices,” which helps us understand how fast light travels through materials such as liquid and air.

Segregation prevented him from attaining university positions. In the fall of 1876, Bouchet moved to Philadelphia where he taught at the Institute for Colored Youth (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania), the city’s only high school for Black students. He remained there for 26 years, educating many Black youths in science, and serving as an inspiration to generations of young Black people.

In commemoration of Edward Bouchet, Yale has convened seminars and lecture series in his name, bestowed the Bouchet Leadership Awards in Minority Graduate Education, and hung an oil painting of him in a prominent spot at the main library. In 1918, the year Bouchet died, Elmer Imes became the second Black American to receive a Ph.D. in physics.

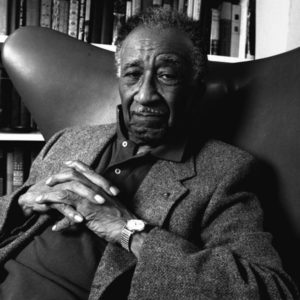

Albert Lee Murray (1916-2013)

Photo: Suzanne Mapes / Associated Press

Albert Lee Murray was one of the most important Black thinkers of the 20th century. Born in Nokomis, Alabama, his mother gave him up for adoption to Hugh and Mattie Murray. He grew up in the Magazine Point area of Mobile, Alabama.

Murray attended the Tuskegee Institute (now the Tuskegee University) on scholarship where he attained a B.S. degree in education in 1939. He went on to teach literature and composition at Tuskegee in 1940. Murray joined the U.S. Army Air Force in 1943 and transferred to the U.S. Air Force Reserve in 1946. He attended New York University on the G.I. Bill and graduated with a M.A. in English in 1948. During this period he became acquainted with Duke Ellington and solidified a friendship with a Tuskegee classmate, Ralph Ellison, who later wrote the classic novel Invisible Man. He also became close friends and a mentor to jazz musician Wynton Marsalis.

In 1962, after a doctor diagnosed heart disease, he retired from the Air Force as a major and moved with his family to Harlem.

Murray is best known through his pugnacious essays. His first collection of essays, The Omni-Americans: New Perspectives on Black Experience and American Culture (1970), attacked false perceptions of Black American life. The book, a punishing critique of Black separatism, insisted that America was a nation of multicolored people who share a common destiny. In the introduction, he wrote that “the United States is in actuality not a nation of Black people and White people. It is a nation of multi-colored people.” Writer Walker Percy called it “the most important book on Black-White relations in the United States, indeed on American culture, published in this generation.”

Murray changed the way people talked about race by challenging Black separatism and insisting that the Black experience was central to American culture. He once remarked that American society is “incontestably mulatto” because Black and White people are inextricably bound to one another.

He recorded his visit to scenes of his segregated boyhood during the 1920s in his second published work, South to a Very Old Place (1971), which was reviewed by Toni Morrison in The New York Times, and became a finalist for the National Book Award.

In Stomping the Blues (1976), Murray maintained that blues and jazz musical styles developed as affirmative responses to misery; he also explored the cultural significance of these music genres and other artistic genres in The Hero and the Blues (1973), The Blue Devils of Nada (1996), and From the Briarpatch File: On Context, Procedure, and American Identity (2001).

Murray also co-wrote Count Basie’s autobiography, Good Morning Blues (1985), and was active in the creation of the concert series Jazz at Lincoln Center. In addition, he published Trading Twelves: The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray (2000), a poetry collection, and a tetralogy of novels—Train Whistle Guitar (1974), The Spyglass Tree (1991), The Seven League Boots (1995), and The Magic Keys (2005).

He held visiting lectureships, fellowships, and professorships at several institutions, including the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism (1968), Colgate University (1970; 1973; 1982), the University of Massachusetts Boston (1971), the University of Missouri (1972), Emory University (1978), Drew University (1983), and Washington and Lee University (1993). From 1981 to 1983, he was an adjunct associate professor of writing at Barnard College. He also received honorary doctorates from Colgate (Litt.D., 1975) and Spring Hill College (D.H.L., 1995).

Murray received great attention in the 1980’s and 1990’s due to his influence on jazz musician Wynton Marsalis. Together the two co-founded Jazz at Lincoln Center.

Albert Murray died in Harlem in August, 2013.

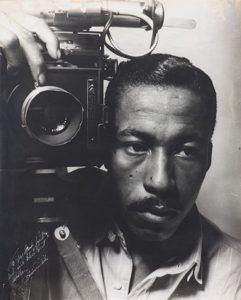

Gordon Roger Alexander Buchanan Parks (1912-2006)

Gordon Parks, Self-Portrait, 1941, Private Collection.

Gordon Roger Alexander Buchanan Parks was an American photographer, musician, writer and film director, who became prominent in U.S. documentary photojournalism from the 1940s through 1970s—particularly in issues of civil rights, poverty, and Black Americans. He was born in Fort Scott, Kansas, the youngest of 15 children. His father was a tenant farmer. His mother instilled in him the strong conviction that dignity and hard work could overcome bigotry.

Parks attended a segregated elementary school. His high school was integrated because the town was too small to have segregated high schools. His teacher told him that his desire to go to college would be a waste of money because he would end up as a porter anyway.

Parks’ mother died when he was 14 and he was sent to live with a sister in St. Paul, Minnesota. After being turned out onto the street at age 15 by an angry brother-in-law, he lived by his wits, struggling to survive as a piano player, bus boy, traveling waiter, and singer. He never finished high school.

In 1937, while working as a waiter on the North Coast Limited passenger train, Parks was struck by photographs of Depression-era migrant workers in a magazine. The photos reminded him of his own struggles and inspired him to purchase his first camera, a life-changing decision. He later told a Life interviewer in 1999, “I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs. I knew at that point I had to have a camera.” He bought his first camera at a pawn shop and taught himself how to take photos.

While filming fashions in a woman’s clothing store in St. Paul, his work caught the eye of Marva Louis, the wife of heavyweight boxing champion, Joe Louis. She encouraged Parks to move to Chicago where he began a portrait business specializing in photographs of society women. At the same time, he began capturing the myriad experiences of Black Americans across the city. He was asked to join the Farm Security Administration (FSA) which was chronicling the nation’s social conditions.

Over the next few years, he began to photograph the city’s South Side Black ghetto and, in 1941, an exhibition of those photographs won him a photography fellowship with the FSA.

During his work for the FSA in Washington, D.C., Parks encountered a cesspool of bigotry. The office had separate eating and lavatorial arrangements for Blacks and Whites. On his first day, he took a photo of Ella Watson, a Black charwoman who mopped floors in the FSA building. The photo, which appeared on the front page of The Washington Post, became known as American Gothic, after the iconic 1930 painting by Grant Wood.

Though his career as a photographer spanned six decades, it is the period from 1940 to 1950, the dawn of the modern civil rights movement, which most significantly defined his point of view as a Black artist and documenter of American life. During that decade, he used his camera to shine a light on the injustices faced by Black Americans, showing the challenges of poverty, violence, and oppression that defined the decade. In the midst of World War II, his photographs made a bold statement about the disparities between the promise and realities of the American Dream. Parks chose to “fight back” against the inequalities he witnessed; his choice of weapons was a camera.

Below is a small sampling of his photographs depicting Black children at home, taken in Washington, D.C. in 1942.

After the FSA disbanded in 1943, Parks remained in Washington, D.C. as a correspondent with the Office of War Information (OWI) where he photographed the Tuskegee Airmen. Unable to follow the group overseas, he resigned from the OWI and renewed his search for photography jobs in the fashion world. He moved to Harlem and became a freelance photographer for Vogue magazine, where he developed the distinctive style of photographing his models in motion rather than in static poses. During this time, he published his first two books, Flash Photography (1947) and Camera Portraits: Techniques and Principles of Documentary Portraiture (1948).

A 1948 photographic essay on a young Harlem gang leader won Parks a job as the first Black staff member on America’s leading photo-magazine, Life. His involvement with Life would last until 1972. For over 20 years, Parks produced photographs on subjects including fashion, sports, Broadway, poverty, and racial segregation, as well as portraits of Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Muhammad Ali, Alexander Calder, and Barbra Streisand. He became “one of the most provocative and celebrated photojournalists in the United States.”

His photographs for Life magazine, illuminated the effects of racial segregation while simultaneously following the everyday lives and activities of families in and near Mobile, Alabama. While Parks’ photo essay documented the Jim Crow South and all of its effects, he did not simply focus on demonstrations, boycotts, and brutality that were associated with that period; instead, he emphasized the “prosaic details” of the lives of several families.

In addition to photography, Parks channeled his literary energy into memoirs. His first story, based on his memories of his childhood in Kansas became the novel, The Learning Tree, which was followed by A Choice of Weapons (1966), Smile in Autumn (1979) and Voices in the Mirror: An Autobiography (1990) and Half Past Autumn (1997).

In 1969, Parks became a film director with the movie version of The Learning Tree. He also was the first Black director of a major film, Shaft, in 1971, which helped to shape the “Blaxploitation” era in the ’70s. Parks also directed the Shaft sequel in 1972.

Parks died in his Manhattan apartment in 2006 at the age of 93. An exhibition of photographs from a 1950 project Parks completed for Life was exhibited in 2015 at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Next week I will continue to honor Black History Month by sharing ways you can honor Black Americans every day. And since March is Women’s History month, I will share the biographies of Black women whose names deserve to be remembered.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

CORRECTION:

A shout out to Patricia Conte-Nelson for pointing out that Daniel Hale Williams did not conduct the first open-heart forgery, as indicated in my newsletter last week. He conducted the first open-heart surgery. Apologies to Dr. Williams’ memory.