Combating Racism – Honoring Women’s History Month – Part 2

In this week’s newsletter, I continue to honor Women’s History Month by highlighting the accomplishments of four little-known Black women—a writer, an educator, a lawyer, and an activist.

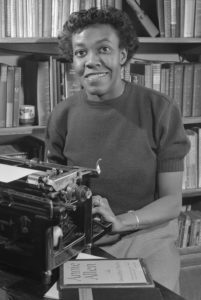

GWENDOLYN BROOKS (1917-2000)

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks was born on June 7, 1917, in Topeka, Kansas. Her father, a janitor for a music company, had hoped to pursue a career as a doctor but sacrificed that aspiration to get married and raise a family. Her mother was a school teacher as well as a concert pianist trained in classical music. Brooks’ mother had taught at the Topeka school that later became involved in the famous Brown v. Board of Education racial desegregation case. Family lore held that Brooks’ paternal grandfather had escaped slavery to join the Union forces during the American Civil War.

When Brooks was six weeks old, her family moved to Chicago during the Great Migration, and from then on, Chicago remained her home. She started her formal education at Forestville Elementary School on Chicago’s South Side. Brooks then attended the prestigious integrated Hyde Park High School in the city with a predominantly White student body. She transferred to Wendell Phillips High School; and finished her schooling at integrated Englewood High School.

During her schooling, Brooks faced much racial injustice. Over time, this experience helped her understand the prejudice and bias in established systems and dominant institutions, not only in her own surroundings but in every relevant American mindset.

Brooks considered a four-year college degree to be unnecessary because she knew she wanted to be a writer. She graduated in 1936 from a two-year program at Wilson Junior College, now known as Kennedy-King College, and worked as a typist to support herself while she pursued her writing career.

Brooks began writing at an early age with her mother’s encouragement. Her first poem, “Eventide”, was published in American Childhood when she was 13. By the time she had graduated from high school in 1935, she was already a regular contributor to The Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper.

By the age of 16, she had already written and published approximately 75 poems. At 17, she started submitting her work to “Lights and Shadows,” the poetry column of the Chicago Defender. Her characters were often drawn from the inner city life that Brooks knew well. In her early years, she received commendations on her poetic work and encouragement from authors James Weldon Johnson, Richard Wright, and Langston Hughes.

By 1941, Brooks was taking part in poetry workshops at the new South Side Community Art Center. Here she gained momentum in finding her voice and a deeper knowledge of the techniques of her predecessors. In 1944, she achieved a goal she had been pursuing through continued unsolicited submissions since she was 14 years old: two of her poems were published in Poetry magazine’s November issue. In the autobiographical information she provided to the magazine, she described her occupation as a “housewife.”

Brooks published her first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville (1945), after author Richard Wright showed strong support with the publisher, Harper & Brothers. Wright told the editors:

[Brooks] takes hold of reality as it is and renders it faithfully. . . . She easily catches the pathos of petty destinies; the whimper of the wounded; the tiny accidents that plague the lives of the desperately poor, and the problem of color prejudice among Negroes.

The book earned instant critical acclaim for its authentic and textured portraits of life in Bronzeville. A glowing review by Paul Engle in the Chicago Tribune stated that Brooks’ poems were no more “Negro poetry” than Robert Frost’s work was “White poetry”. Brooks received her first Guggenheim Fellowship in 1946 and was included as one of the “Ten Young Women of the Year” in Mademoiselle magazine.

Brooks’ second book of poetry, Annie Allen (1949), focused on the life and experiences of an ordinary young Black girl growing into womanhood in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago’s South Side. The book was awarded the 1950 Pulitzer Prize for poetry, making Gwendolyn Brooks the first Black author to be awarded the coveted prize.

In 1953, Brooks published her first and only novel titled Maud Martha, which follows the life of a Black woman named Maud Martha Brown as she moves about life from childhood to adulthood. Maud suffers prejudice and discrimination not only from White individuals but also from Blacks with lighter skin tones, a direct reference to Brooks’ personal experience. Eventually, Maud stands up for herself by turning her back on a patronizing and racist store clerk. “The book is … about the triumph of the lowly,” wrote Harry B. Shaw in his book, Gwendolyn Brooks.

In 1967, the year of Langston Hughes’s death, Brooks attended the Second Black Writers’ Conference at Nashville’s Fisk University. Under the pressures of McCarthyism, Brooks adopted a Black nationalist posture, which inspired many of her subsequent literary activities. She taught creative writing to some of Chicago’s Blackstone Rangers, a violent criminal gang. In 1968, she published one of her most famous works, In the Mecca, a long poem about a mother’s search for her lost child in a Chicago apartment building. The poem was nominated for the National Book Award for poetry.

Her autobiographical Report From Part One, including reminiscences, interviews, photographs and vignettes, came out in 1972, and Report From Part Two was published in 1995, when she was almost 80.

Brooks’ first teaching experience was at the University of Chicago where she taught a course in American literature. It was the beginning of her lifelong commitment to sharing poetry and teaching writing. Brooks taught extensively around the country and held posts at Columbia College Chicago, Northeastern Illinois University, Chicago State University, Elmhurst College, Columbia University, and the City College of New York.

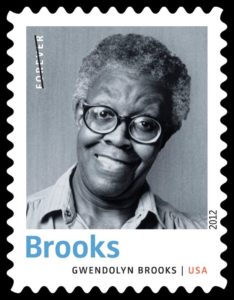

Gwendolyn Brooks was the recipient of numerous honors, including a Guggenheim Fellow in Poetry (1946), induction into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1976), induction into the National Women’s Hall of Fame (1988), recipient of the Robert Frost Medal for Lifetime Achievement (1989) and the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters (1994), to name just a few. In 1968, she was appointed Poet Laureate of Illinois, a position she held until her death. In 1985, she was selected as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, known as the Poet Laureate of the United States, becoming the first Black woman to hold that position. She was presented with the National Medal of the Arts in 1995.

Gwendolyn Brooks died at her Chicago home on December 3, 2000, aged 83. In April 2012, the U.S. Postal Service honored her on a commemorative forever stamp as part of the Twentieth Century Poets set. Today Brooks is considered to be one of the most revered poets of the 20th century, whose works reflected the political and social landscape of the 1960’s, including the civil rights movement.

CHARLOTTE HAWKINS BROWN (1883- 1961)

Charlotte Hawkins Brown was born in Henderson, North Carolina in 1883 to descendants of slaves. In 1888 the family moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, near Boston, to escape Jim Crow and segregationist practices of the South and for better social, economic, and educational opportunities. Though one of few Black students in Cambridge’s schools, young Brown was an excellent student, and by chance she met educator Alice Freeman Palmer, who became her mentor and benefactor.

Palmer was so impressed by Brown’s diligence at pursuing an advanced education that she helped sponsor Brown’s schooling. She also introduced Brown to many important society people in Boston—people Brown would later approach to help with her school.

After a year of junior college, Brown accepted a $25-a-month job from the American Missionary Association (AMA) and returned to her home state of North Carolina to teach poor, rural Black students.

She arrived at rundown Bethany Institute in Sedalia in 1901. Her desire to help southern Blacks drove her to begin repairing the school, but unfortunately the AMA decided to close it. Though now jobless, Brown was encouraged by local Blacks to start her own school. The 18-year-old nearly single-handedly made it happen.

After securing money and encouragement from her friends in the North, she moved the school across the street to a Blacksmith’s shed. Brown soon raised enough money to build a campus with more than 200 acres and two new buildings. Unlike trustees at other schools of that period (even Black institutions), the school’s board of trustees members were all Black Americans. After hiring a small staff and garnering the additional support of local Black and White leaders, Brown began operations of Palmer Memorial Institute (Palmer), named in memory of her friend and benefactor, Alice Freeman Palmer.

Among other attributes, the school offered Black youth an unusual opportunity for cultural learning. Its goal was to be a facility where Blacks could escape the then-common assumption that Blacks were innately inferior to Whites and did not need any schooling beyond vocational training.

In 1900 North Carolina had more than 2,000 privately operated schools for Black students. Most teachers, however, had only an elementary school education so could only instruct their students up to that level. Palmer was different because Brown offered college preparatory instruction in a junior and senior high school setting. Classes included drama, music, art, math, literature, and romance languages. Students were divided into small circle groups with teachers who served as counselors and advisers. Each student received personal training in character development and appearance. Additionally, all students had to work one hour per day for the school as service learning.

By 1915 Brown had gained support from national figures such as educational leader Booker T. Washington, Harvard University president Charles William Eliot, and Boston philanthropists Carrie and Galen Stone.

After a major fire destroyed two of six main buildings in 1917, Brown raised enough money to prevent the school’s closing. This successful effort also encouraged increased biracial support for Palmer. Donors supported the school because of its holistic approach to total education and its quality liberal arts programs, geared to educating Black students beyond basic training levels.

Renewed biracial support and increased contributions from across the nation helped fund Palmer’s first major brick building and a new status as the only accredited rural high school for Blacks or Whites, in Guilford County. Brown introduced more liberal arts classes and advanced math and science courses for Palmer students. They even studied African American history at a time when no other North Carolina high school was teaching it.

Brown took a year off to travel and study. In Europe she shared ideas with Black educators Mary McLeod Bethune and Nannie Helen Burroughs. By the mid-1920s Brown was a nationally known speaker who stressed teaching these concepts through culture and liberal arts for racial uplift. Palmer’s growing reputation increasingly drew middle- and upper-class students from outstanding families in the United States, Africa, Bermuda, Central America, and Cuba.

In 1937 Brown closed the elementary and junior college departments and convinced Guilford County officials to open the county’s first public rural high school for Black students. At the state level, she helped create the first school for delinquent Black girls. She became known as the “first lady of social graces” after appearing on national radio and publishing the book, The Correct Thing to Do, to Say, to Wear in 1940. In the mid-1940s Brown raised $100,000 for an endowment, and Ebony magazine published a feature article on prestigious Palmer as “the only…school of its kind in America.”

In 1952 Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown retired after 50 years as the leader of the Palmer Memorial Institute. She handpicked Wilhelmina M. Crosson of Boston to succeed her as Palmer’s next president. Following a long illness, Brown died in 1961 and was buried on the campus she loved.

Palmer Memorial Institute has since become a state historic site. Located east of Greensboro, it was the first state-supported site to honor the contributions of Black Americans and women. Ongoing programs highlight the history and development of Black education in North Carolina. By the end of the 1950s, the Institution enrolled over 200 students.

The Institute prepared students for future academic study, and graduates generated an impressive track record of academic performance. Approximately 90% of graduates attended college, and 64% of them went on for postgraduate work.

After Brown’s death, the Institution experienced financial setbacks, in part because desegregation laws allowed Blacks to attend formerly White-only public schools. A 1971 fire destroyed the administration and classroom building, and the trustees were forced to close the school.

The Palmer Institute reopened in 1987 as the Charlotte Hawkins Brown Memorial State Historic site. It is the only state historic site dedicated to the achievements of a Black American and the accomplishments of a woman.

EUNICE HUNTON CARTER (1899-1970)

Eunice Roberta Hunton was born in Atlanta, the granddaughter of enslaved people. Her parents, prominent educators and activists, moved to Brooklyn, New York when Eunice was five following the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906.

In 1921 she became only the second woman in the history of Smith College to receive a bachelor’s and a master’s degree, having done so in four years and graduating cum laude. Following her graduation, she worked as a social worker before marrying dentist Lyle Carter in 1924. After the birth of her son, she began studying law at Fordham University. In 1932 she became the first Black woman to receive a law degree from Fordham Law School—a time when few lawyers were Black or women, let alone Black women. Two years later she became the first Black woman to pass the New York State Bar.

Carter entered politics in 1934 when she was nominated by the Republican Party to represent New York’s 19th District in the State Assembly. The first Black American to gain the Republican nomination for that office, Carter’s campaign centered on the need to reduce the age limit for pension, enforce compliance with legal standards for tenement housing, and continue unemployment insurance. She also opposed racial discrimination in public works employment. Carter narrowly lost by 1,600 votes.

Carter was working as a social worker in New York City when, following the Harlem riots in 1935, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia appointed her as a prosecutor in what was then called “women’s court”—a court for the prosecution of women, especially prostitutes. She became the first Black female assistant district attorney in the state of New York and began working as a prosecutor in the New York County (Manhattan) District Attorney’s office. She became a key assistant to special prosecutor Thomas Dewey. It is in that capacity that she is credited with establishing key facts in the prosecution of mobster Charlie “Lucky” Luciano.

In her work as prosecutor in the “women’s court,” she realized that women arrested for prostitution from all over New York City were represented by the same lawyers and bail bondsmen. And those agents had a relationship with “Lucky” Luciano. She discovered that prostitutes were required to kick back half of their earnings to crime bosses in exchange for legal representation. In effect, brothels in New York were controlled by Luciano’s mob; he was profiting from prostitution.

She brought that information to Dewey and meticulously built a case that led to 200 raids of brothels in the city and finally the conviction of Luciano in 1936, at that time the most powerful racketeer in the country. Carter provided the essential legal strategy in convicting Luciano, whose prosecution earned her the title “Lady Racketbuster.” But the credit for Luciano’s downfall went to the young prosecutor, Thomas Dewey, who eventually ran for president.

Luciano was sentenced to 30 to 50 years. (He was released from prison and deported to Italy 11 years later in exchange for his help in preventing problems on the New York City docks during World War II.)

Carter continued working with Dewey and the District Attorney’s Office until 1945, when she entered private practice. In 1947, Carter was one of fifteen American women invited to attend the first International Assembly on Women in Paris, to discuss “human and educational problems affecting peace and freedom.”

She connected her work with the National Council of Negro Women to international issues. In 1955, she was elected to chair the International Conference of Non-Governmental Operations. Two years later she attended the United Nations-sponsored Commission on the Status of Women in Geneva, the European headquarters of the United Nations. While there she was elected Chair of the Conference of International Organizations in Consultative Status with the United Nations. She also served on the Executive Committee of the International Council of Women.

She was the real-life heroine who inspired a character on the HBO series Boardwalk Empire. She died in New York City in 1970 at the age of 70.

SEPTIMA POINSETTE CLARK ( 1898 – 1987)

Septima Poinsette was born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1898, the daughter of a laundrywoman and a former slave. She graduated in 1916 from the Avery Normal Institute and, after passing her teacher’s exam at age 18, began her career as a school teacher in a Black one-room schoolhouse in Johns Island, just outside of Charleston. During this time, she taught children during the day and illiterate adults on her own time at night and developed innovative methods to rapidly teach adults to read and write, based on everyday materials like the Sears catalog.

She wanted to do more to advance the rights of Blacks and she joined the Charleston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was under the guidance of Edmund Austin, the President of the Charleston chapter of the NAACP, that Clark took part in her first political action. Against her principal’s orders, she led her students around the city, going door-to-door, asking for signatures on a petition to allow Black principals at Avery Institute. She got 10,000 signatures in a day and in 1920 Blacks were given the right to become principals in Charleston’s public schools.

While teaching at Avery, she met Neerie David Clark, who worked as a warden cook on a Navy submarine during World War I. She and Neerie wrote letters back and forth and dated for nearly three years. The couple married in 1923. Clark’s mother believed that, to marry a man outside of the state is to marry a stranger, and she severed the relationship with her daughter.

Due to the color of her skin, Clark was not allowed to teach in the Charleston public school system, and instead had to accept teaching positions in rural school districts. She became aware of the gross discrepancies that existed between her school and the White school across the street. Clark’s school had 132 students and only one other teacher. Clark made $35 per week. The nearby White school had three students and a teacher who earned $85 per week. Her first-hand experience with these inequalities led Clark to become an active proponent for pay equalization for teachers and enter the movement for civil rights. Clark and others protested to win Blacks the right to teach at Charleston public schools. She participated in a class action lawsuit filed by the NAACP that led to pay equity for Black and White teachers in South Carolina. Clark became convinced that social activism had the power to better the lives of Black Americans.

Clark pursued her education during summer breaks. In 1937 she studied under W. E. B. Du Bois at Atlanta University before eventually earning her BA (1942) from Benedict College in Columbia, and her MA (1946) from Virginia’s Hampton Institute.

In 1956 South Carolina passed a statute that prohibited city and state employees from belonging to civil rights organizations. Her involvement in the NAACP did not go unnoticed by the Charleston City School Board. Clark was asked to leave the NAACP, but when she refused, the school board fired her. She lost her pension after 40 years of teaching. No longer employed, she devoted all of her time to activism.

By the time of her firing in 1956, Clark had already begun to conduct workshops during her summer vacations at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, a grassroots education center dedicated to social justice. After losing her teaching position, Myles Horton hired Clark full time as Highlander’s director of workshops. Believing that literacy and political empowerment are inextricably linked, Clark worked tirelessly to teach Black people basic literacy skills, their rights and duties as U.S. citizens, and how to fill out voter registration forms.

While Black men and women had the right to vote, they were often kept from the voting polls by literacy tests. Many adult Black Americans could not read because their parents and grandparents were formerly enslaved, and until 1865, it was illegal to teach an enslaved person to read and write. As a result, literacy tests prevented many Black citizens from voting, even into the 1950s and 1960s.

Clark designed educational programs to teach Black community members how to read and write, believing these skills were essential to vote and gain other rights. Her idea for “citizen education” became the cornerstone of the Civil Rights Movement. She worked with Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to win rights for African Americans.

When the state of Tennessee forced Highlander to close in 1961, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) established the Citizenship Education Program (CEP), modeled on Clark’s citizenship workshops. Clark became SCLC’s director of education and teaching, conducting teacher training and developing curricula. Although Clark found that most men at SCLC “didn’t respect women too much,” she thought that Martin Luther King, Jr. “really felt that Black women had a place in the movement.”

After retiring from SCLC in 1970, Clark conducted workshops for the American Field Service. In 1975 she was elected to the Charleston, South Carolina, School Board. The following year, the governor of South Carolina reinstated her teacher’s pension after declaring that she had been unjustly terminated in 1956.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter awarded her a Living Legacy Award in 1979. Her second autobiography, Ready from Within: Septima Clark and the Civil Rights Movement, won the American Book Award.

Septima Clark continued to serve as an advocate and a leader until her death in 1987. Known as the “Grandmother of the American Civil Rights Movement,” she was an educator and civil rights activist who played a major role in the voting rights of Black Americans.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Watch for next week’s newsletter as I continue to honor Women’s History Month with the biographies of four additional remarkable yet unfamiliar Black women.